The most mysterious and indeed mythical ship in the U.S. Navy never sailed and was never completed, commissioned, or crewed. Her history is fraught with controversy, misunderstanding, and misperceptions. Yet, for all this, the aircraft carrier United States (CVA-58) is an important inflection point in the Navy’s history.

The controversy surrounding her cancellation just five days after her keel had been laid can best be understood by separating fact from fiction. The popular or prevalent understanding is that the United States was a big-deck carrier in the vein of the present-day Nimitz and Gerald R. Ford classes, as well as of the predecessor Forrestal, Kitty Hawk, John F. Kennedy, and Enterprise classes. But that is not fact.

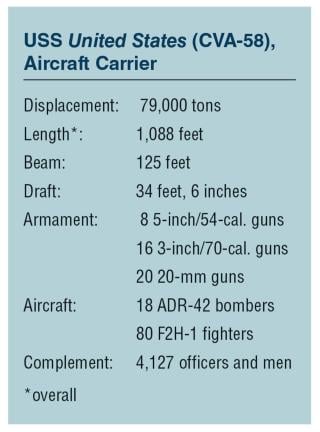

The United States was to be built with the primary purpose of carrying and supporting nuclear-attack bombers. Her notional air-wing complement would consist solely of 18 very heavy bombers and 80 escort fighters. Other aircraft carriers would provide her defensive air cover.

In late April 1945, the Navy seriously began to contemplate the successor class to the 58,600-ton Midway large aircraft carriers (CVBs) constructed at the end of the war. That summer, the Bureau of Ships (BuShips) began considering designs in the range of 35,000 to 50,000 tons.

The proposed C-1 study was for a ship of 39,600 tons—larger than the Essex class, but smaller than the Midways. The Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer), however, pushed for larger bombers that carried loads of 8,000 to 12,000 pounds—to include 4,000-pound “blockbuster” bombs and coincidentally nuclear weapons—and carriers to support them. It developed studies based on proposed turboprop-driven bombers of three classes, the largest of which—type C at 100,000 pounds—required a new class of carrier.

The service proposed the rapid development of the type B bombers (45,000 pounds), which could be operated with some restrictions from the Midways. The type B became the AJ-1 Savage. In January 1946, Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher pressed Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz to develop a new carrier and the large aircraft. Mitscher’s wartime experience off the coast of the Philippines had impressed on him the need for longer-range aircraft (thus larger and heavier) and the larger ships from which to operate them. Further, he believed in flush-deck—no superstructure island—carriers that would allow the operation of even larger aircraft.

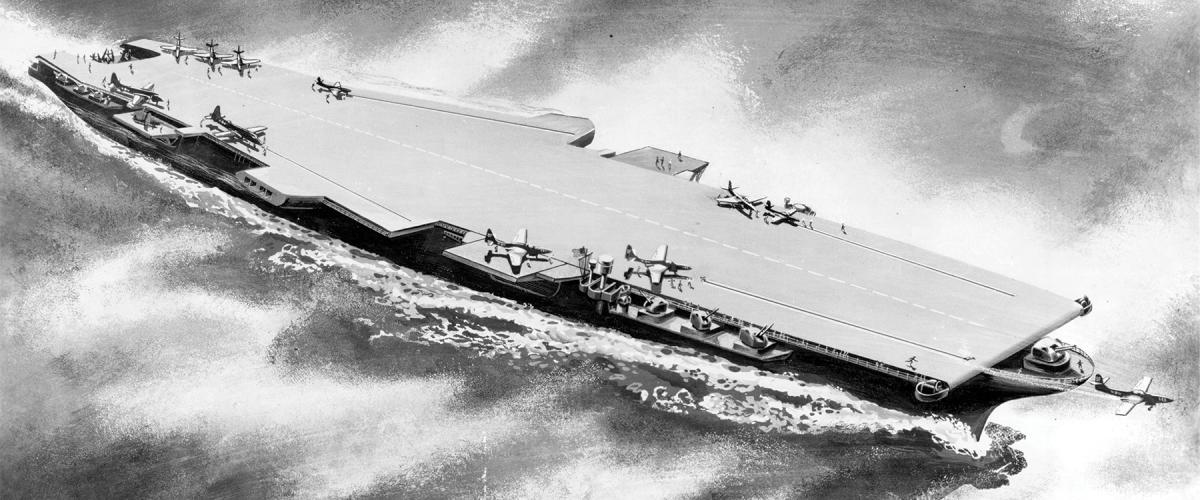

The Ship Characteristics Board (SCB) began studies using a BuAer design study aircraft of 100,000 pounds designated ADR-42. For real-world figures, the SCB used the Lockheed P2V Neptune, the Navy’s largest land-based bomber. What resulted were sketch designs for CVB-X, a single-purpose ship designed solely for atomic strikes by 100,000-pound bombers. It was a 1,190-foot carrier with a 130-foot beam displacing 69,200 tons standard and 82,000 tons trial. With a small island and uptakes, it was not a true flush-deck carrier. Because it would not have a hangar deck, the ship’s 24 ADR-42 aircraft would be stored and maintained on the flight deck. No other aircraft were to be carried; fighter protection would be provided by “at least two” accompanying carriers.

Because aviators still had questions about the limitations posed by the island and uptakes and the ADR-42 data on which to base the ship’s final design was incomplete, it was recommended that the design, now designated 6A, not be included in the 1948 shipbuilding program but remain funded as a design study.

In February 1947, the SCB produced proposed characteristics for the 6A. It would have a hangar deck that could accommodate its 12 to 18 ADR-45A attack aircraft and 54 XF2D-1 (later F2H Banshee) fighters, or 12 ADR-42s with an equal number of the same fighters. The ADR-45A was a smaller, 57,000-pound aircraft.

On 22 August, the SCB recommended that the CNO approve the proposal for BuShips to prepare preliminary plans. The carrier was estimated to have a waterline length of 1,000 feet, beam of 125 feet, and displacement of 60,000 tons standard. The air group was increased to 18 ADR-42s or 27 ADR-45As and 80 fighters.

CNO Nimitz approved the proposal on 2 September, and the same day it was submitted to the Secretary of the Navy in the Fiscal Year 1949 Shipbuilding and Conversion Program. The acting Secretary approved it the next day. But the Bureau of Budget did not approve the request because of ongoing construction costs from the 1946 budget. The Navy agreed to forgo some construction—including completion of the battleship Kentucky (BB-66) and large cruiser Hawaii (CB-3)—in exchange for approval of the carrier. This was agreed.

In May 1948, when the Navy testified before Congress in support of the 1949 budget, Secretary of the Navy John L. Sullivan and CNO Admiral Louis Denfeld stated that the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) had approved the appropriation. The Air Force objected, and Secretary of Defense James Forrestal referred the matter back to the JCS. Three of its four members approved the carrier; the Air Force Chief of Staff did not. Nevertheless, the ship went forward.

The Navy originally intended to build four 6A carriers, one in each fiscal year from 1949, with all operational by 1955. But during Senate Appropriations Committee testimony, Secretary Sullivan described the 6A carrier as a “prototype” and said it was a “very great mistake” to build more of them until the first one was built and operated. Congress authorized construction in the 1949 program and provided initial funding. On 22 July 1948, Sullivan approved a new ship classification for the carrier—CVA (heavy aircraft carrier)—and designated it CVA-58. President Harry S. Truman authorized its construction the next day.

The Air Force continued its opposition to not only the flush-deck carrier but also the Navy’s existing CVB and CV fleet carriers. In March 1949, with the forced resignation of Forrestal, Louis A. Johnson was named to become Secretary of Defense. The Air Force would gain a perceived ally in the new leadership and began to force the issue. After Forrestal’s resignation was announced but before he left office, Air Force Chief of Staff General Hoyt S. Vandenberg sent a memo to Forrestal defining in no uncertain terms the service’s position on the “supercarrier.” Its purpose was “to prevent Congress” from further committing to approving the carrier.

On 15 April, after just 18 days in office, Johnson sent a letter to General of the Army Dwight Eisenhower, who was serving as a consultant to the Secretary of Defense, asking for the judgment of the JCS on the carrier. Eisenhower stated he had not investigated the matter and did not intend to until he heard from the Joint Chiefs. At Johnson’s order, a copy of his letter to Eisenhower was distributed to each JCS member. Although Johnson professed “no preconceived notions” about proceeding with the carrier, nevertheless, the Navy was shaken by this request. The next day, it began working on a “very comprehensive” defense of the project.

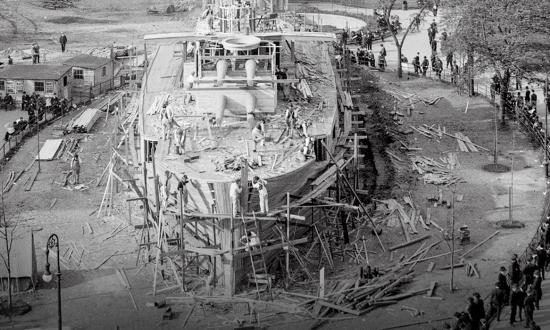

On 18 April, Johnson met with Secretary of the Navy Sullivan and asked him if he were to start over again would he still build the ship. Sullivan answered in the affirmative and began to cite his reasons. Johnson summarily cut him off, citing other pressing business. As he left the office, Sullivan told Johnson he would be out of town for two days and asked “do I have your word” that nothing would be done on this until they had spoken again. Johnson replied, “You have my word.” Later that day, the keel of the newly named United States was laid at the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company.

The next day, the JCS decided that each would reply individually to Johnson’s request, with a deadline of the afternoon of the 22nd. The Army and Navy responses arrived on time, but it was early evening before that of the Air Force was delivered. The JCS secretary had to assemble the responses early the next day, and they were forwarded to Johnson’s office at 1030 later that morning.

Barely half an hour later, the Navy received a mimeographed press release stating construction of the carrier had been terminated just five days after having been laid down. It included a memorandum in which Johnson professed his “careful consideration and discussion of the matter with the President.” There is much circumstantial evidence that such was not the case, and that Johnson never discussed the matter with the Navy or with General Eisenhower.

Johnson never stated his reason for canceling the ship, but it was assumed to be part of his proclaimed need for drastic economic cuts. But his real reason was that he saw the Navy’s desire for the big-deck carrier as a means of competing with the Air Force and that while he was Secretary of Defense, “the Navy would have no part in long range or strategic bombing.”

The loss of the ship was not the end of the story. Missing is the vitriolic undercurrent of animosity between the nascent Air Force, which was desperately fighting to claim as much turf as possible, and the long-established Navy, which was arguing to maintain its position at the table.

In the wake of the cancellation of CVA-58, Secretary Sullivan, along with Under Secretary of the Navy John Kenney, resigned. This vacuum led to “even greater attacks” by the Defense Secretary on the Navy, especially Navy Air. The CVA-58 episode was the prelude to the so-called Revolt of the Admirals. Just a year later, the start of the Korean War proved to be the impetus for the creation of a new type of supercarrier—the Forrestal class. The CVA-58 concept was a strategic dead end; its cancellation was the right call.

Author’s Note: The majority of political references in this article are from Jeffrey Barlow’s Revolt of the Admirals (Naval Historical Center, 1994).