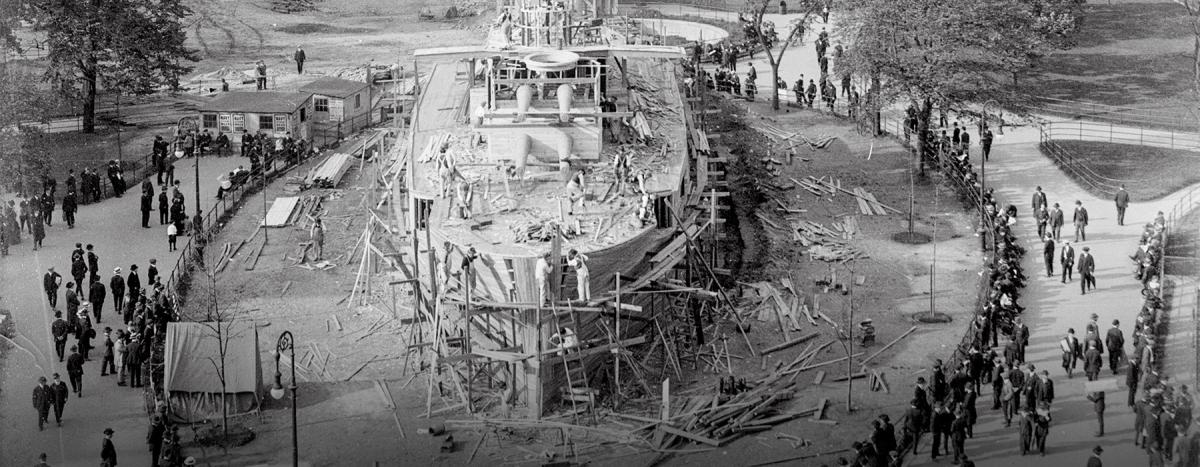

“This big ship is advertising propaganda, pure and simple,” is how Blain Ewing, chairman of New York City Mayor John P. Mitchel’s Defence [sic] League in May 1917 described the “USS Recruit,” under construction in the city’s Union Square. A month after the United States entered World War I, the city was behind in providing its quota of men to the Navy. The Army had the draft to fill its rolls, but the Navy and Marine Corps had to rely on recruitment. The Recruit was to serve not only as a recruiting vehicle, but also as a training “ship” and a hands-on interface between the Navy and general public.

The Defence League believed it “pays to advertise” and proceeded to do so in New York fashion, if not style.

The Recruit was paid for by conscription through the league office; no taxpayer or Navy money was used in her construction. Nevertheless, some questioned a great expenditure of money during wartime on a ship that would not—and could not—sail. Ewing would say only that she cost in excess of $10,000. Materials were sold to the league at or below cost, the construction company donated its services and supervisors, and other companies donated much of the Recruit’s equipment.

When completed, the structure somewhat resembled a battleship. The completely wooden recruiting station mounted three twin-gun main battery turrets with 14-inch guns and ten secondary battery 5-inch guns in hull-mounted barbettes. All weapons were also wooden. She had a single stack standing 18 feet above the superstructure, a conning tower, and 50-foot-tall cage masts at the fore and main.

The Recruit was christened by the mayor’s wife on 30 May 1917 “in the presence of one of the largest crowds ever assembled” in the square. The mayor presented the ship to the Navy, and she was accepted by Rear Admiral Nathaniel R. Usher, commandant of the New York (Brooklyn) Navy Yard. Command was turned over to Commander Charles A. Adams, a veteran of the Civil and Spanish-American wars.

Recruiting offices for both the Navy and Marine Corps were within the landship. Also inside were a large waiting room for recruits and applicants, showers, toilet facilities, offices for doctors, and examination rooms both fore and aft. Popular Science Monthly noted there was a “ventilating device, which changes the temperature ten times every sixty minutes.” Above the recruiting spaces, the structure was made to appear as ship-shape as possible. Bluejackets from the Brooklyn Navy Yard installed “various nautical apparatus, mystifying to a landlubber” for a fully equipped bridge. Two smaller weapons, variously described as machine guns or two models of one-pounder breech-loading rifles, also were mounted. Crewmen manning them gave gunnery demonstrations.

Life on board the Recruit was “ordinary Navy routine.” The crew had reveille at 0600, ate mess, scrubbed decks, laundered clothing, attended classes and trained, stood guard, and answered visitors’ questions. Watches were stood to 2300, and from sundown searchlight projectors on board the facility illuminated the skyline around the square.

In addition to her recruitment and public-relations duties, the landship was a focal point for Liberty Bond drives, dances, boxing matches, and as a set for the 1917 movie Over There. She struck a bit of a fashion note for a time during her nearly three-year commission when she received a dazzle camouflage pattern of green, blue, mauve, white, and black geometric shapes.

By most accounts, the Recruit was successful, with 25,000 Navy recruits to her credit.

After the war, plans were made to move the landship to Coney Island, where she was intended to remain as a recruiting depot at Luna Park. On 17 March 1920, The New York Times reported that “[a]fter riding at anchor” for nearly three years in Union Square, the Recruit “yesterday began a voyage” to Coney Island. After ceremonies at the 1000 “sailing time,” the crew stood at attention on the quarterdeck as the colors were lowered and the “commissioned pennant” was hauled down. It was estimated to take two weeks to dismantle and reconstruct the landship, but the project was abandoned when the cost of moving her exceeded her value. The materials likely were repurposed.