Close Call during the Crisis

Lieutenant Commander James T. Griffin, U.S. Navy Reserve (Retired)

With regard to the Cuban Missile Crisis (“Black Saturday Declassified,”) I was on board the USS Enterprise (CVN-65) when she abruptly stood out of Norfolk as President John F. Kennedy was telling a shocked world that Soviet offensive missiles were in Cuba.

As we steamed south, the air group trapped aboard under clear, moonlit skies. Quick as the flight deck swarms could do so, the aircraft were struck below, where ordnance swarms hung full loads of bombs and rockets on the racks of the A-4 Skyhawks and A-1 Skyraiders and Sidewinder and Sparrow missiles from the pylons of F-4 Phantoms and F-8 Crusaders. Within hours, the air wing was fully loaded; 112 aircraft were ready for God only knows what.

The next morning at breakfast, Bob Lyman, our explosive ordnance disposal officer, curled our crew cuts with a tale whose portent was too horrific to contemplate. He was making the rounds of the nearly 70 fully loaded planes on the hangar deck in the wee hours of the morning. Nearing a sentry next to a Skyhawk on the darkened deck, Bob’s heart nearly leaped out of this throat. Steeling himself to calm, Bob scuffled his feet while harrumphing to alert the bored sentry. The young sailor straightened himself, and Bob beckoned him to come over. As the sentry stepped away from the parked plane, Bob immediately went over to it.

The sentry had been idly twisting a little propeller vane at the front of one of the plane’s bombs. Bob, of course, knew that the propeller was the bomb’s fuse! It spins as the bomb falls through the air until the spring unloads to cock the fuse, so that when the front of the bomb contacts the ground, the fuse will explode it. Bob was unsure if the propeller was fully unwound.

The A-4 was gingerly pushed by hand to the aft starboard aircraft elevator. When the “Big E” was dead in the water, the aircraft crane, ever so slowly, lowered the fully loaded A-4 into the dark depths of the Atlantic.

What if the Enterprise and her escorts had disappeared in a blinding flash as they steamed to Cuba? The world was on edge that night with the President’s announcement. High drama indeed.

The Navy’s Military Laws

David Burkey

I received my August Naval History and read Commander Todd Moe’s article “Port Chicago Revisited.” The author cites the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ), but it was not used by the U.S. Navy in World War II; the Navy still used the Articles for the Government of the Navy. The UCMJ was not in effect until 31 May 1951.

Commander Moe responds:

The letter’s author raised a valid point that deserves clarification. As members of the Navy, the “Port Chicago 50” would have been subject to Articles for the Government of the United States Navy, first issued in 1930. The Uniform Code of Military Justice was promulgated well after World War II. However, a reading of the Navy articles shows that World War II–era sailors could only be court-martialed and punished if they “disobey the lawful orders of his superior officers.”

As highlighted in my article, the Navy court of inquiry charged with investigating the Port Chicago disaster acknowledged that Navy leadership purposefully disobeyed Coast Guard safety regulations found in Title 46 of the U.S. code. Military orders violating federal law cannot be considered lawful even in the historical context of the Navy articles. When Seaman Small and his division refused to offload ammunition at Mare Island in August 1944, they were disobeying an illegal order. As such, there was no basis for their conviction by court-martial.

To Surrender or Not

Commander Allen E. Fuhs, U.S. Navy Reserve (Retired)

The USS Pueblo (AGER-2) article in the June issue (“Judge Awards Pueblo Survivors, Families $2.3B in Damages,”) stimulates this brief commentary that involves my friend, Richard Lewis, from our Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps (NROTC) days at the University of New Mexico. We maintained contact for decades after commissioning in 1951.

By 1968, the time of the Pueblo incident, Commander Richard Lewis was commanding officer (CO) of a nuclear boat. One night at the bar just before departing on a cruise, the officers of Dick’s submarine were debating whether or not the CO of the Pueblo made the correct decision to surrender. Lewis indicated that as CO he would never surrender.

Word spread rapidly among the crew of Lewis’s boat that the CO would be unyielding if faced with surrender. Commander Lewis’s wife spent the next 90 days assuring the other wives that their husbands were in safe hands.

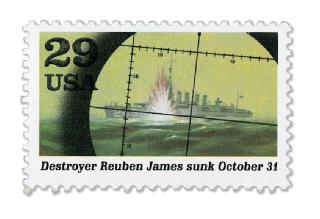

Ill-Fated Destroyer’s Stamp

Terry Miller and Morgan Little

In reference to the article showcasing postage stamps depicting U.S. Navy ships (“Pieces of the Past,”), we at Tin Can Sailors thought readers might be interested to know about another such stamp, one that honors the destroyer USS Reuben James (DD-245). Sunk by the German U-boat U-552 in the North Atlantic on 31 October 1941, before the United States had officially entered World War II, she was the first U.S. Navy ship sunk in the conflict. The Reuben James stamp was issued by the U.S. Postal Service in 1991 as part of the “1941: A World at War” commemorative stamp block.

Tin Can Sailors serves destroyer veterans and their families through publications, events, and more, as well as by supporting numerous destroyer museum ships. To find out more, visit www.destroyers.org.