Seventy-five years ago this July, mushroom clouds—billowing, towering, weirdly majestic in their terrible magnitude—filled the sky for the first time since the Hiroshima-Nagasaki bombings that had ended World War II the year previous. Operation Crossroads, the U.S. Navy’s July 1946 atomic-bomb tests at the Marshall Islands’ Bikini Atoll, inspired a new addition to the modern lexicon: The French fashion designer Louis Réard named his daring two-piece ladies’ bathing suit the “bikini” after the test that had just transpired. (Ironic it is how a name that instantly conjures carefree summer fun should have been spawned from a grimly serious trial of warfare capabilities.)

Ninety-five target ships filled Bikini Lagoon, and on 1 July 1946, bomb test “Able” saw the dropping of the atom bomb nicknamed “Gilda” (after the 1946 movie Gilda, starring “bombshell” Rita Hayworth), to be followed on 25 July with the dropping of “Helen of Bikini” in bomb test “Baker.”

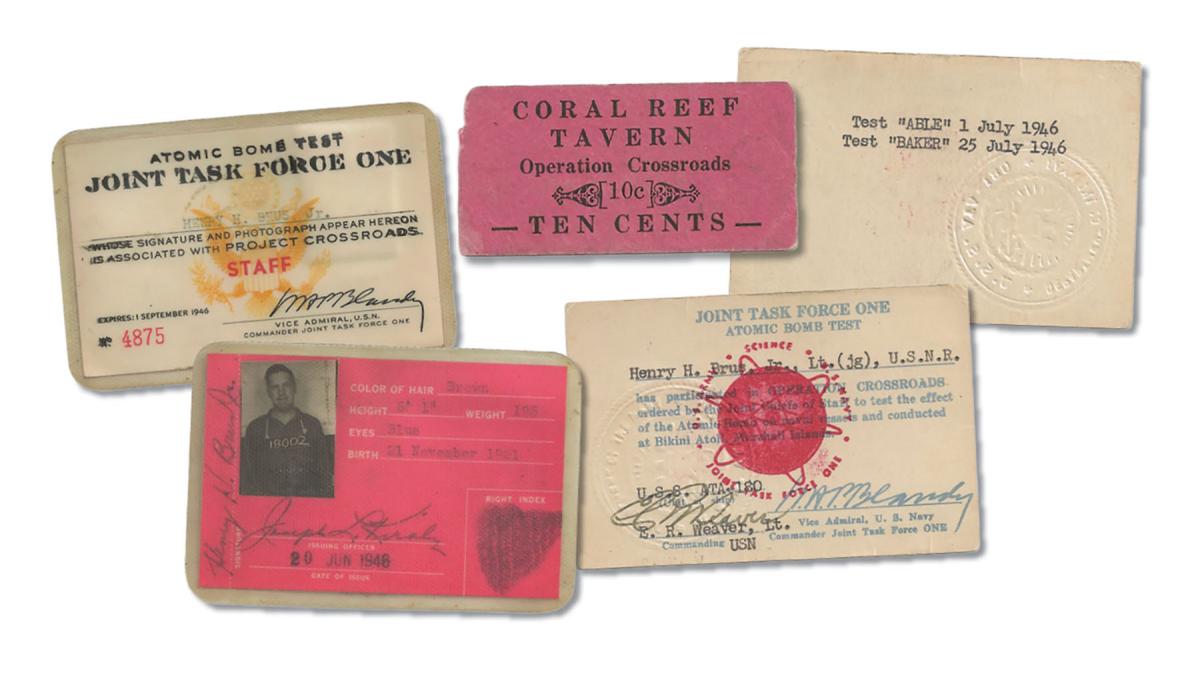

To have been assigned to Operation Crossroads is to have been present for a profound and unforgettable scene at the dawn of the Cold War. Such a witness to history was Lieutenant (j.g.) Henry H. Brus Jr., U.S. Naval Reserve, who served as executive officer on board the auxiliary fleet tug USS ATO-180 in Joint Task Force One. Among his related mementoes, now in the collection of his son, Henry H. Brus III, one finds his Operation Crossroads participant card, his Joint Task Force One ID card, and, to top things off, a 10-cent token for Operation Crossroads’ exclusive “Coral Reef Tavern,” a lean-to that served as an ad hoc beach bar.

“I have been present at both of the tests here at Bikini,” Lieutenant Brus wrote home in a letter, “and I cannot write a description that will satisfy myself, nor have I seen any other account that would do justice to the scene. There was a burst of flame from the center of the array that shot out in all directions like a flash of lightning and was immediately replaced by smoke. From the center of this rose a vertical column like a massive pillar several thousand feet high. At what I estimated to be 3,000 feet it began to mushroom out into a billowy white cloud. This cloud had a slight peach tint and grew very rapidly.”

The lieutenant felt his words, or any words, failed to capture the cataclysmic spectacle. In grasping for language to describe how it felt standing at that “crossroads” of history, he was in good company. Robert J. Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb, similarly overwhelmed by the ramifications of this new and perilous age, had scrapped coming up with words of his own and instead famously resorted to a line from Hindu scripture: “Now I am become Death—the destroyer of worlds.”

—Eric Mills