Honda Point, also known as Point Pedernales, is located just north of the entrance to the Santa Barbara Channel in Santa Barbara County, California. The area has been known to be hazardous as far back as the 16th century, when Spanish explorers coined the area the “Devil’s Jaw” due to its treacherous and plentiful rocky outcroppings. Local mariners have long known to avoid the area at all costs, and the sailors involved on the 8 September 1923 incident were no exception. However, a perfect storm of radio and navigational errors, irregular currents, and poor visibility all came together at just the right time to result in the largest peacetime loss of U.S. Navy ships, and the tragic deaths of 23 men.

The story of the Honda Point disaster finds its beginning seven days earlier and some 5,000 miles away, when the Great Kantō earthquake tore through the main Japanese island of Honshū on 1 September 1923. With a magnitude of 7.9 on the moment magnitude scale, the earthquake shattered the cities of Tokyo, Yokohama, and the much of the surrounding prefectures. Well over 100,000 lives were lost in the quake, and the damage to Japan’s infrastructure was estimated to have exceeded $15 billion dollars in today’s currency. As a result of the mighty earthquake, unusually large swells and powerful currents swept through Pacific Ocean, reaching as far as the California coastlines.

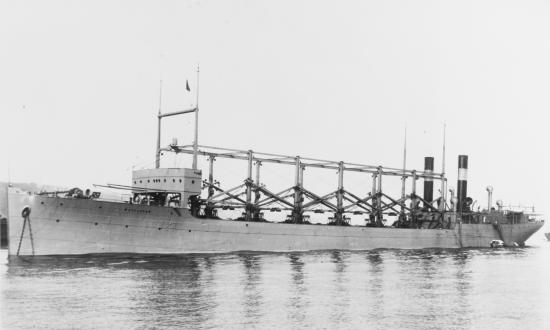

Despite the unusually rough conditions on the Pacific, the U.S. Navy deployed 14 Clemson-class destroyers of Destroyer Squadron 11 (DesRon 11) from San Francisco Bay to San Diego Bay for training exercises on 8 September 1923. Led by Captain Edward H. Watson, the ships of DesRon 11 conducted a series of tactical and gunnery exercises during their journey between the Bays. At the time of this incident, radio navigation aids were a relatively recent addition to navigational departments and were not yet wholly trusted by navigators aboard ships. The ships in DesRon 11 thus relied on dead reckoning for the bulk of their navigation, and only used radio navigation aids as a supplement to their preferred methodology.

As the day progressed, weather conditions worsened and reduced the visibility surrounding the destroyers. Captain Watson, who flew his flag aboard the USS Delphy (DD-261), had DesRon 11 form a column on the Delphy to decrease the risk of any mishaps. Using dead reckoning, the navigator aboard the flagship determined that the squadron was ready to turn east into the entrance of the Santa Barbara Channel at 21:00. The radio navigation aids aboard the Delphy indicated that they were off course by several miles northeast, but the squadron’s navigator believed the reports to be erroneous and chose to ignore them in favor of his own calculations. Though the squadron could have stopped to take soundings of water depths to confirm safe passage, Captain Watson had DesRon 11 simulating wartime conditions as an exercise and did not want his ships to reduce their speeds. Captain Watson ordered the ships to travel in close formation and barreled into what he believed to be the Santa Barbara Channel at a speed of 20 knots. Heavy fog blanketed the area and concealed the perils of what was actually Honda Point from their sights.

Unfortunately, the men of DesRon 11 would not realize their mistake until it was too late. A mere 5 minutes after turning east, the Delphy plowed ashore at 20 knots. Sailors aboard the Delphy scrambled to sound the ship’s siren, but the wheels of disaster were already well in motion. The USS S.P. Lee (DD-310) saw the Delphy come to a sudden stop a few hundred yards ahead and quickly turned to port to avoid the flagship but swung herself broadside into the nearby bluffs instead. The USS Young (DD-312) made no move to change her course and sailed directly over a series of sharp, submerged rocks which tore a gaping hole in her hull. As the Young capsized onto her starboard side, rushing water trapped much of her fire and engine crew in the lower compartments of the ship. The USS Woodbury (DD-309), USS Nicholas (DD-311), and the USS Fuller (DD-297) all struck rocks and ran aground in shallow waters. Stunned by the unfolding chaos, men aboard the USS Chauncey (DD-296) decided to make way to the capsizing Young to save her crew, instead crashing ashore nearby.

While the perilous rocks of the Devil’s Jaw ensnared the first 7 ships of DesRon 11’s column, the blaring sirens of the damaged vessels bought time for the remaining 7 destroyers in the latter half of the formation. The USS Farragut (DD-300) and the USS Somers (DD-301) slowed just enough to hit the ground but were able to back up and out of danger. The USS Percival (DD-298), USS Kennedy (DD-306), USS Paul Hamilton (DD-307), USS Stoddert (DD-302), and USS Thompson (DD-305) avoided the disaster altogether by breaking formation and diverting their courses.

The sound of sirens, twisting metal, and shouting sailors did not go unnoticed by locals in the area. Nearby fisherman raced to the area to gather sailors from the wrecked ships, and ranchers rigged up breeches buoys from atop the bluffs to haul men away from the danger. The five destroyers of DesRon 11 that avoided the rocks immediately jumped into rescue efforts, sending out lifeboats and to collect men and bring them back to the safety of their decks. While the disaster occurred on 8 September, the last of the sailors were not rescued until the afternoon of 9 September. When all was said and done, 7 destroyers were declared a total loss, and 23 men, 20 aboard the Young and 3 aboard the Delphy, were lost in the catastrophe.