It was a tragedy on a historic scale for the U.S. Navy, and it has been the stuff of otherworldly speculation for decades—and to this day, just what happened to the USS Cyclops (AC-4) in 1918 remains one of the enduring mysteries of the sea.

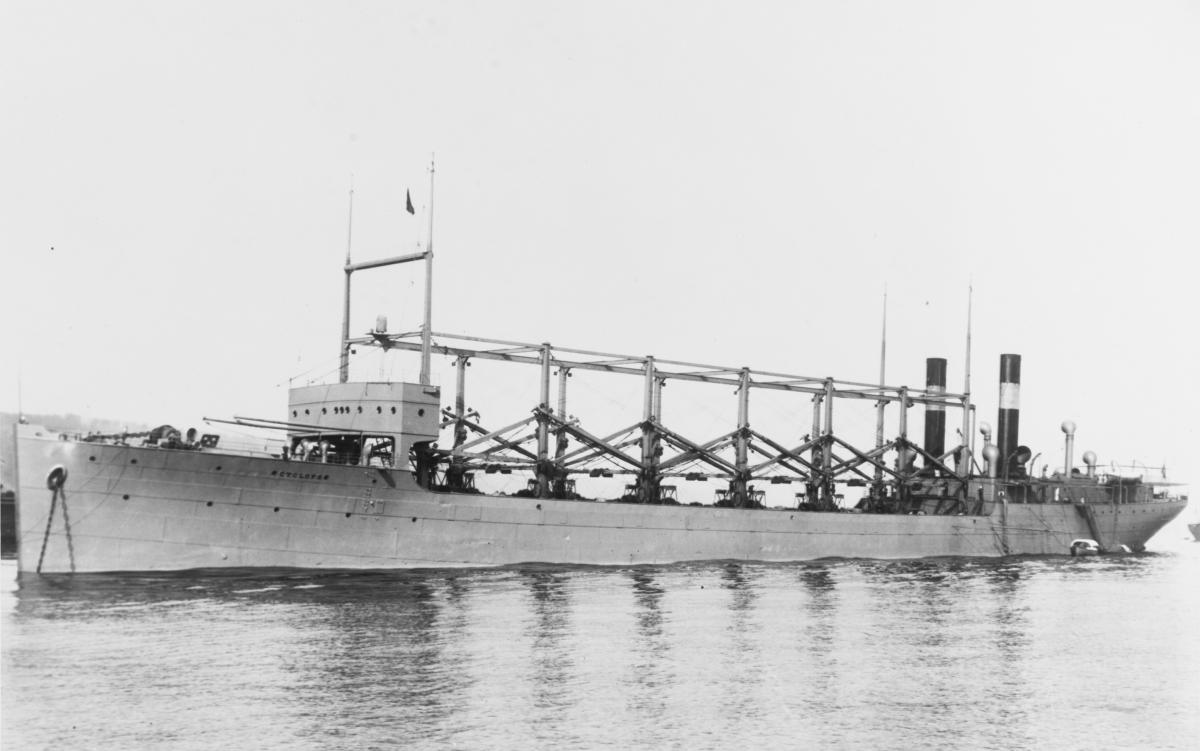

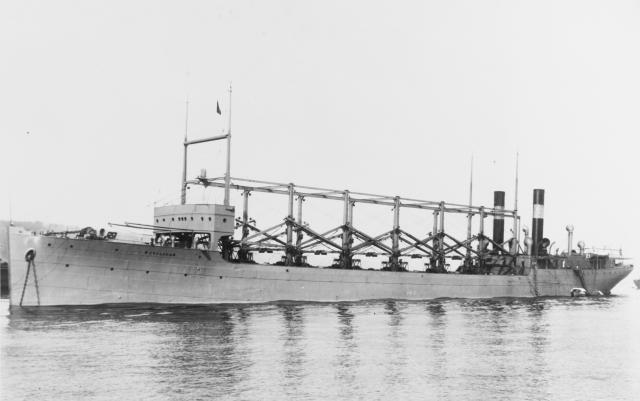

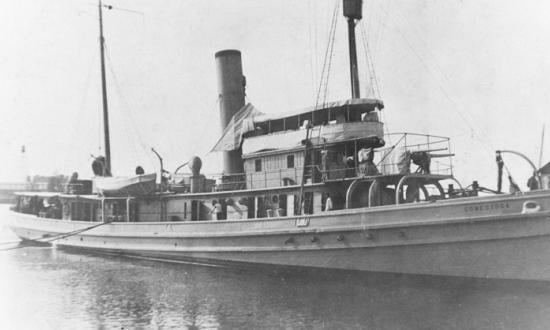

The Proteus-class collier was launched on 7 May 1910 by William Cramp & Sons in Philadelphia. Second of her class and of her name, she was placed in service on 7 November 1910. The Cyclops’ first seven years of service were reasonably routine. She spent May to July 1911 in the Baltic, followed by a period of operation along the U.S. East Coast and the Caribbean, and she participated in support of refugee evacuations during the U.S. occupation of Veracruz, Mexico, in 1914–15.1

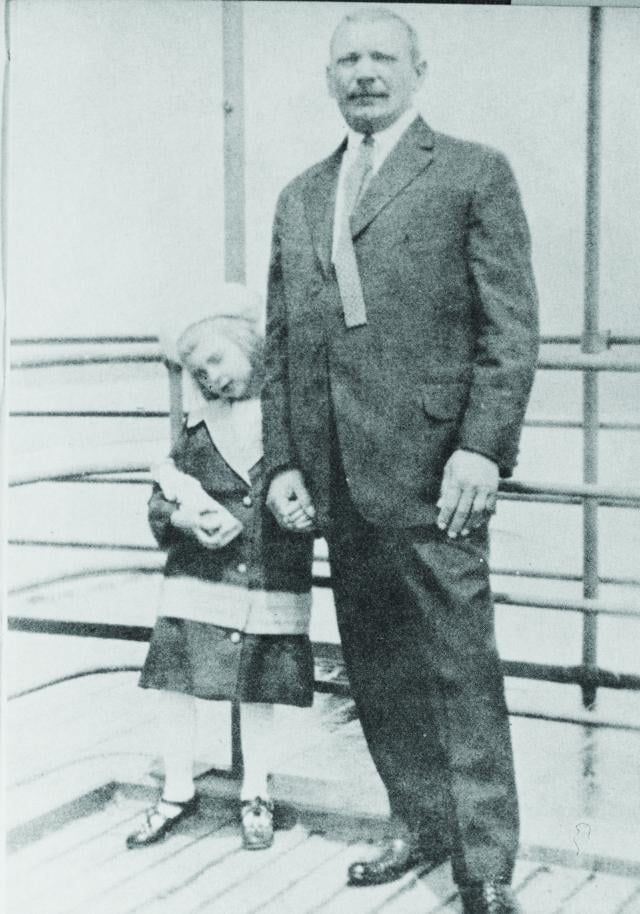

On 1 May 1917, as was the case with many vessels at the time, the Cyclops was commissioned for duty in World War I. With Lieutenant Commander George Worley in command, she began her wartime duties in June, joining a convoy bound for St. Nazaire, France. Returning to the East Coast in July, she spent the bulk of 1917 serving in the area, save for a brief excursion to Halifax, Nova Scotia. On 9 January 1918, the Cyclops was assigned to the Naval Overseas Transportation Service and made way to Brazilian waters to refuel British warships.2

On 16 February 1918, the Cyclops departed from Rio de Janeiro, reaching Salvador on 20 February. From there, she was to deliver a load of manganese ore to Baltimore, Maryland. Prior to her departure from Rio, Commander Worley had submitted a report detailing structural concerns surrounding the Cyclops: The starboard engine had cracked and one of the cylinders was no longer operational. Despite his concerns, the survey board that received his report recommended he make way for the United States anyway, where the ship could then be brought up to snuff. In addition to the potentially compromised state of the ship’s engine, it was reported that she carried a load weighing around 10,800 tons, in addition to 4,000 tons of water in her hull, placing her well over the limit she was able to carry safely. Indeed, the Cyclops made an unscheduled stop in Barbados only a few days after departing Rio because the water level was noticeably over the ship’s Plimsoll line. Despite these concerns, the Cyclops stocked up on fuel and other provisions during her stop, further weighing her down.3

On 4 March, the Cyclops departed from Barbados to make her way to Baltimore, where she was expected to arrive on 13 March. She supposedly was sighted by the molasses tanker Amolco on 9 March off the coast of Virginia; however, the captain of the vessel later denied the sighting. Given that she was due in Baltimore on the 13th, it made little sense for the Cyclops to be so close to her destination so far before her scheduled date of arrival. The following day, on 10 March, the Amolco and various weather services reported a massive, destructive storm in the general vicinity.4 The 13th of March came and went, and there was no sign of the Cyclops in or around Baltimore.

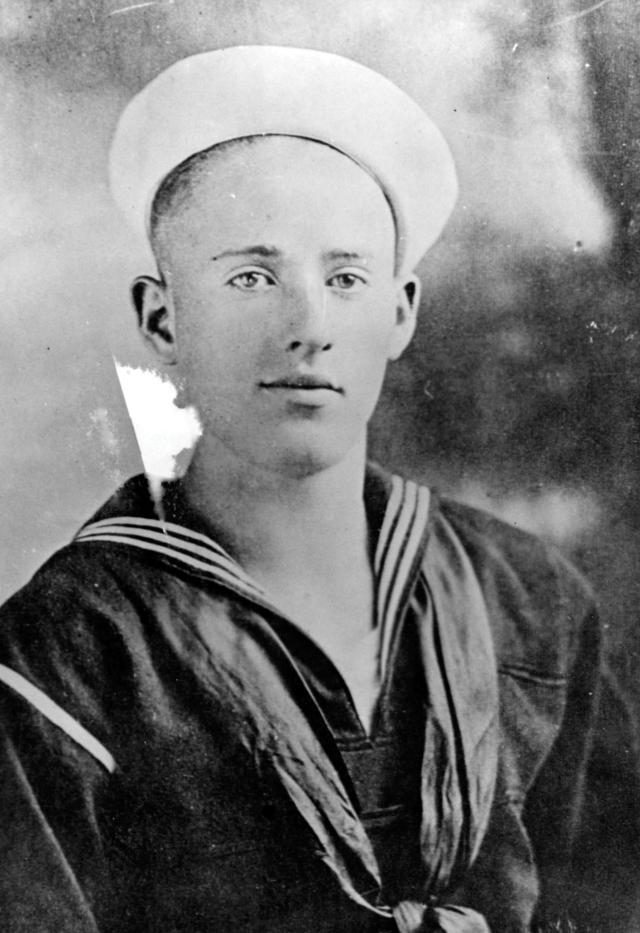

To this day, there remains no sign of the Cyclops anywhere at all. For all intents and purposes, she and the 306 men on board seem to have disappeared without a trace. On 1 June 1918, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt declared the Cyclops lost and all hands deceased.

There are several theories that seek to explain the loss of the Cyclops. Given that her disappearance occurred during wartime, many believed that she was struck and sunk by a German U-boat or raider attack, as her cargo would have made her a prime target.5 However, as the war drew on and more intelligence was gathered, it became increasingly unlikely that there were any enemy vessels in the area at the time of her disappearance.

Both Commander Worley and his crew were eyed as main players in her disappearance as well. Worley supposedly wrote to the Bureau of Operations of the Navy Department to complain of his crew in 1917, noting their lack of training or experience in seafaring, and even going so far as to say the engines had suffered due to their inability to care for the ship’s equipment.6

Conversely, the crewmen of the Cyclops had their own ill feelings toward Worley, claiming he was an eccentric drunk who often mistreated the men under his command.7 Prior to her disappearance, there were even reports of a mutiny on board the Cyclops, though it was quickly brought under control and those involved were swiftly punished.8

Another theory attributes her disappearance to the ever-mysterious Bermuda Triangle, as she did traverse the area on her voyage.9 Some naval personnel wondered if the Cyclops suffered from deeper structural failures, such as the corrosion of I-beams due to the chemical nature of some cargo, a flaw that was noted in some of her sister ships.

Whatever caused the USS Cyclops and her 306 souls on board to disappear in March 1918, it was the single largest loss of life not directly related to combat in U.S. naval history.

1. Mark L. Evans, “Cyclops II (Fuel Ship No. 4),” Naval History and Heritage Command, 6 September 2018.

2. Evans, “Cyclops II (Fuel Ship No. 4).”

3. Alfred P. Reck, “Strangest American Sea Mystery Is Solved at Last,” Popular Science Monthly 114, no. 6 (June 1929): 15–17, 137.

4. Reck, “Strangest American Sea Mystery Is Solved at Last.”

5. Natasha Frost, “Bermuda Triangle Mystery: What Happened to the USS Cyclops?” History.com, 31 July 2018; updated 20 December 2019.

6. Reck, “Strangest American Sea Mystery Is Solved at Last.”

7. Frost, “Bermuda Triangle Mystery: What Happened to the USS Cyclops?”; Howard L. Rosenberg, “Exorcizing the Devil’s Triangle,” Sealift, no.6 (June 1974): 11–15.

8. Rosenberg, “Exorcizing the Devil’s Triangle.”

9. Rosenberg.