The Curtiss F-5L flying boat probably has the most convoluted history of any aircraft.1 Its predecessors saw action in the Great War (1914–18) and established the flying boat as a key component of naval aviation. Historian Kenneth M. Molson wrote:

One of the most significant aviation developments of World War I was that of the large flying boat, which advanced from a low powered, relatively frail machine to one with excellent seaworthiness and ability to carry out regular patrols of 5–6 hours, and occasionally longer, over the North Sea. In addition, encounters with Zeppelins, German seaplanes and submarines showed that these machines were able to give an excellent account of themselves in engagements with the enemy.2

The popular F-5L could trace its antecedents to 1913, when the London Daily Mail offered a prize of £10,000 for the first crossing of the Atlantic Ocean by air. Among the many aircraft that sought that distinction were two Curtiss Model H flying boats, one of which John C. Porte hoped to pilot to win the prize. Porte had been invalided out of the Royal Navy in 1911, the victim of pulmonary tuberculosis. That same year he obtained a civilian pilot certificate.

The start of the war in 1914 brought a halt to the transatlantic flight attempts, and Porte rejoined the Royal Navy. He soon was able to convince the Admiralty to purchase the two Curtiss “America” boats, as they were dubbed, and they were delivered to Britain in November 1914.

Meanwhile, Curtiss developed several military flying boats from the America design. In 1915, the British purchased four of these aircraft, and in Britain the Aircraft Manufacturing Company built eight, all being designated H.4. Porte—now a squadron commander in the Royal Naval Air Service—designed a new boat hull for these aircraft and fitted them with open cockpits and new engines. Although successful, the aircraft were underpowered, even when refitted with the British engines. They were redesignated F.1, the “F” for the Felixstowe air station in Suffolk, England.

Porte further improved the flying boat’s design, and it was put into large-scale production as the F.2, 3, and 5. There were continuing improvements to the hull design, which enabled faster water takeoffs and better “sailing” on the surface of the rough North Sea waters. These aircraft were among the most successful seaplanes of the war. An F.2C prototype was built, but despite marginally better performance, was not placed in production. However, flown by now−Wing Commander Porte, the aircraft sank the German submarine UC-1 on 24 July 1917.

All British variants disappeared from service shortly after the war ended.

Back in the United States, the Navy decided to adopt the British improvements, resulting in the Curtiss H.8 flying boat, referred to as the “Large America.” It was larger than the previous H.4 and entered production for the U.S. Navy as the H.12. This was a four-man aircraft with open cockpits, including a gunner’s position in the nose with twin Lewis machine guns and a rear gunner position with a single Lewis gun. Two 230-pound or four 100-pound bombs could be carried under the wings.

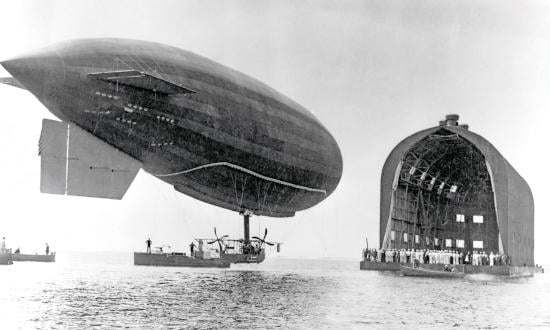

The U.S. Navy acquired 19 H.12s and the interim H.8, and the Royal Navy procured 50 from Curtiss. Later, the British acquired 21 H.12B models that were assembled in the United Kingdom. A British H.12 shot down the Zeppelin L.22 on 14 May 1917, and another sank the submarine UC-36 six days later, evidence of the aircraft’s effectiveness. During the war these flying boats sighted 67 U-boats and attacked 44 of them, with several sinkings recorded. To extend the aircraft’s range, Porte designed a lighter to carry it that would be towed behind a destroyer. This arrangement enabled the aircraft to be towed some distance before taking off.

The largest and most efficient variant of the Model H was the H.16, with the prototype flying in late 1917. The aircraft had an improved hull similar to the Porte design and larger-span wings. The armament was increased with side gun positions, and the payload was increased to four 230-pound bombs.

fleet exercises.

Orders were put forward for 480 of these aircraft from the Naval Aircraft Factory in Philadelphia, which built the prototype. Another 50 were contracted from Canadian Aeroplanes Limited of Toronto, and 60 more from Curtiss. About 125 of these aircraft were to go to Britain.

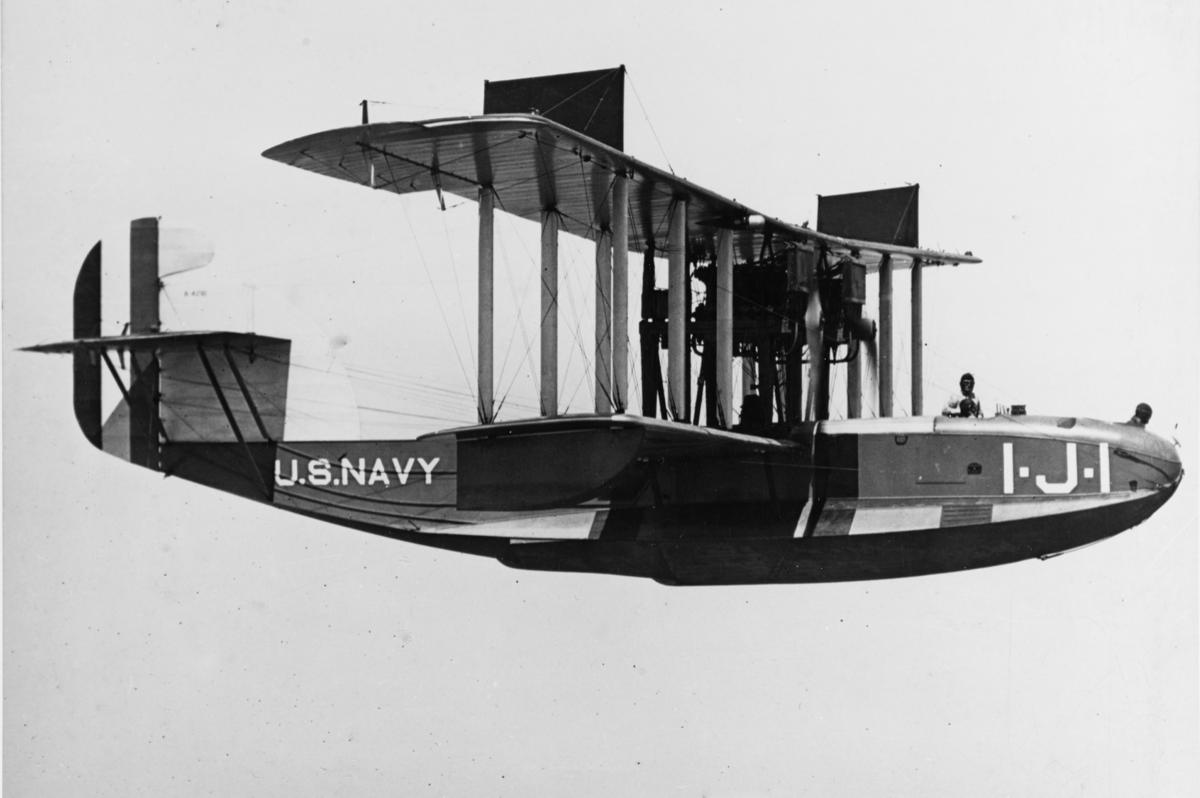

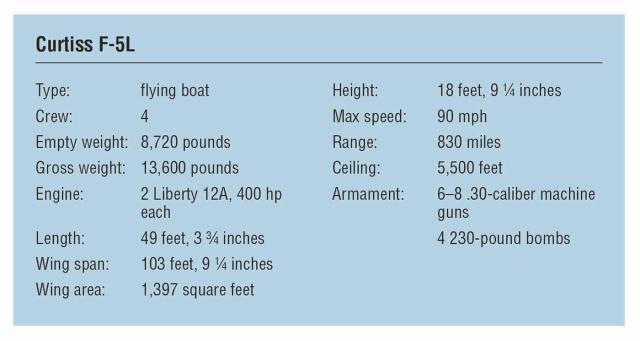

Production of these flying boats—designated F-5L—began in April 1918. The “F” was for the Felixstowe design and the “L” for the Liberty-series engines. When the war ended in November 1918, there were massive cancellations of aircraft orders. Accordingly, the Naval Aircraft Factory delivered only 137 aircraft; the Canadian order was cut to 30; and Curtiss delivered 60 of the flying boats. Two from the Navy facility had modified tail configurations and were known as F-6Ls. Only 75 were delivered to Britain, with 50 of those going directly into storage on arrival and the other 25 being refitted with British engines.

In 1921, the U.S. Navy introduced a new aircraft designation scheme, and the F-5L/F-6L flying boats became PN-5 and PN-6, respectively, “PN” indicating “patrol–navy.” But the aircraft were referred to by their original designations until the last were dropped from the Navy’s inventory in 1928.

The basic F-5L/Felixstowe configuration, especially the “Porte hull,” remained popular, and the Naval Aircraft Factory produced several derivatives designated PN-7 through PN-12, the principal difference being in their engines. After these 12 development aircraft, the PN-12 entered production, with Douglas building 25 PD-1s, Keystone producing 18 PK-1s, and Martin constructing 55 PM-1 and -2 aircraft. These were significant numbers for between-the-wars naval aircraft programs.

After the war, many of these aircraft were acquired by civilian airlines and converted to 16- to 20-passenger transports.

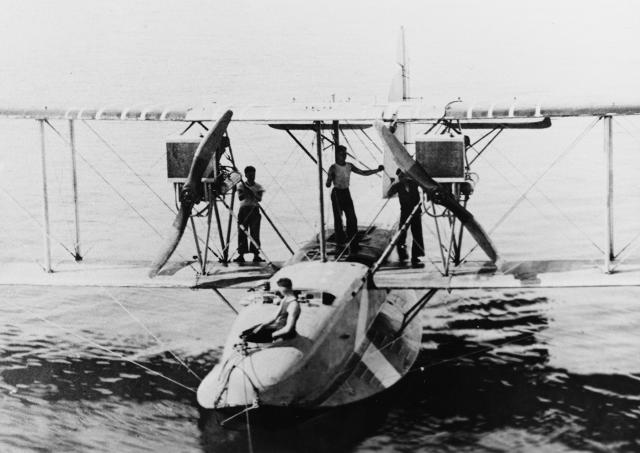

The basic F-5L was a biwing flying boat, with twin engines fitted between the wings, slightly outboard from the carefully shaped wood hull. Stabilizing floats were fitted on the outer section of the lower wing. The later PK-1 and PM-2 aircraft had twin tail fins and rudders.

Although the aircraft had a long and convoluted development from the Curtiss America flying boats to an effective naval patrol/antisubmarine aircraft, it was a tale of great success.

1. This column is based in part on G. R. Duval, British Flying-Boats and Amphibians 1909−1952 (London: Putnam, 1966); Kenneth Munson, Flying Boats and Seaplanes (London: Blandford, 1971), 113−15; and Gordon Swanborough and Peter M. Bowers, United States Navy Aircraft since 1911 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1968), 130−32.

2. Kenneth M. Molson, “The Felixstowe F5L,” Cross & Cockade: Great Britain Journal 9, no. 2 (1978): 49.

3. See “A Transatlantic Flying Boat” [America flying boats], Naval History (June 2008), 66−67.