During the 20th century and into the 21st, mines have sunk more surface ships than any other weapon. In World War II, there were efforts to detect mines from aircraft, as well as attempts to detonate influence mines by aircraft fitted with magnetic devices.

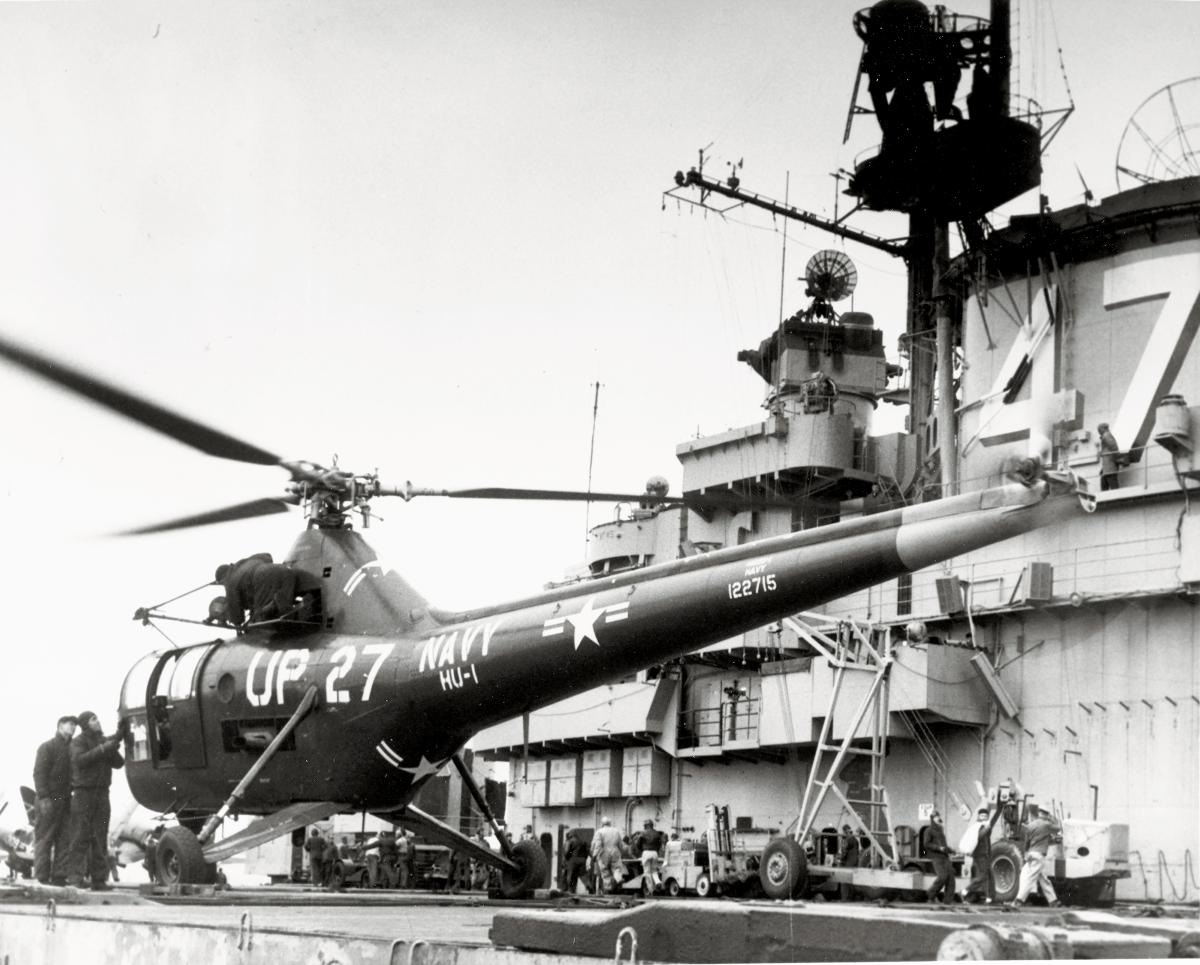

The United States and Great Britain employed fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters for mine-spotting during the Korean War (1950–53). The fixed-wing aircraft were Martin PBM Mariner and Short Sunderland flying boats, but more useful were Sikorsky HO3S-1 helicopters. Normally assigned to utility work on board battleships, cruisers, and aircraft carriers, in the mine-spotting role these whirlybirds flew from land bases and ships, including tank landing ships (LSTs), and from the British light carrier Theseus. They mainly sighted surface or near-surface mines, with a few airmen taking “pot shots” at mines with rifles.1

The promise of helicopters as mine countermeasures (MCM) platforms led to a series of trials at various U.S. Navy laboratories and bases. Following these trials, in 1962 the Navy selected the twin-turbine, tandem-rotor Boeing-Vertol HRB-1 Sea Knight (redesignated H-46A later that year) for the helicopter MCM role. But the Marine Corps wanted all available H-46 production for use in the Vietnam conflict, thus the Navy sought an alternative.

It selected the widely used Sikorsky HSS-2 Sea King (later SH-3), a large antisubmarine aircraft. In 1965, nine SH-3As were converted to the MCM role and redesignated RH-3As. Their antisubmarine gear was removed and provisions were made for towing MCM gear. In September 1966, Helicopter Composite Squadrons 6 and 7 were formed to provide RH-3A detachments to the fleet. These helicopters flew from the MCM support ships Catskill (MCS-1) and Ozark (MCS-2), as well as from land bases.

The Navy determined a more capable helicopter was required for the MCM role, and in 1971 it borrowed 15 CH-53A Sea Stallions from the Marine Corps and established the world’s first helicopter MCM squadron—HM-12—on 1 April 1971, at Norfolk, Virginia. The CH-53 was a twin-turbine helicopter that in the assault role could carry 38 troops or 24 stretchers or lift an external load of 25,000 pounds. Most CH-53s as built were fitted with hard points capable of towing MCM gear. For the mine countermeasures role, these Sea Stallions were provided with upgraded turboshaft engines and redesignated RH-53As.

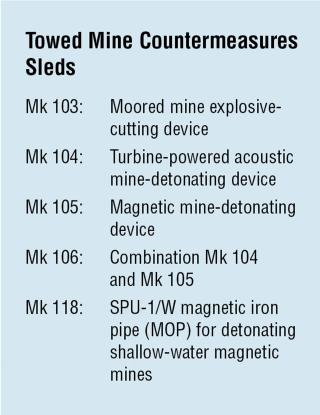

The Navy then ordered 30 specially equipped Sea Stallions, designated RH-53Ds, which were delivered in 1973–74. They had automatic flight controls for sustained low-level flight, AN/APN-82 Doppler radar for precise navigation, an in-flight refueling probe, an additional 500-gallon fuel tank fitted in each sponson, and two .50-caliber machine guns to detonate mines. A variety of MCM “sleds” could be towed by these aircraft (see box on page 11).

(LPD-1) about to lift a Mk 105 hydrofoil minesweeping sled in 1971. U.S. Navy

These helicopters operated off North Vietnam in 1973 (Operation Endsweep) and at the northern end of the Suez Canal in 1974 (Nimbus Star) and again in 1975 (Nimbus Stream).2 Because of their extended range and other features, eight RH-53Ds were deployed on the aircraft carrier Nimitz (CVN-68) in 1980 for Operation Eagle Claw, the attempt to rescue U.S. hostages from Tehran following the Iranian Revolution the previous year. Seven of those helicopters were destroyed in an accident in the desert, and the mission was aborted. (Ironically, six RH-53D helicopters had been produced for the pre-revolution Imperial Iranian Navy.)

The RH-53D also was employed extensively in fleet logistics support, again testimony to its range and lift capability. In 1979, an RH-53D set a nonstop, transcontinental flight record from Norfolk to San Diego, flying the 2,077 nautical-mile route in 181/2 hours with in-flight refuelings from Air National Guard HC-130 Hercules.

Helicopter MCM squadrons HM-14 and HM-16 were established in 1978 for operational fleet deployments with the RH-53. But HM-16 subsequently was disestablished in 1987, with HM-15 being established. A four-helicopter detachment of HM-15 was maintained at Cubi Point in the Philippines until U.S. forces withdrew from that country.

The much upgraded “E” variant of the prototype YCH-53E first flew in 1974; it differs from earlier CH-53s by being fitted with a third turboshaft engine, among other features; its payload capacity is 16 tons. The first flight of the prototype MH-53E Sea Dragon occurred in 1981, and 50 production aircraft eventually were delivered. Another 11 were produced for the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (the last of which was retired in 2017).

The MH-53E replaced the RH-53D in the Navy’s MCM squadrons. The lift capacity and flexibility of the MH-53E led to HM-15 deploying three of these aircraft with 100 men to bases in the Persian Gulf area in 1991–92 for logistics support of Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm.

In the late 1990s, the Navy experimented with laser-based sensor systems for mine detection. The two competing systems were the ML-30 Magic Lantern and ATD-111. They were evaluated on Kaman SH-2F Light Airborne Multi-Purpose (LAMPS) helicopters. The Magic Lantern previously had been evaluated in a combat area during the 1991 conflict in the Persian Gulf. A mine countermeasures “package” based on a laser mine-detection system was being developed for the ubiquitous H-60 Sea Hawk, which would have been designated MH-60S. However, in 2020, the MH-53E remains the U.S. Navy’s only helicopter specifically configured for MCM while awaiting development of the mine countermeasures package for the Sea Hawk.

1. During the Korean War mines sank three U.S. minesweepers and a fleet tug and damaged several other ships.

2. The Soviet missile cruiser–helicopter carrier Leningrad participated in the Suez Canal mine clearance at the southern entrance in 1973–74, with two Mi-8 Hip helicopters; in addition, the ship carried four Ka-25 Hormone utility helicopters.