When the United States entered World War I, the Allies viewed America as the world’s leading industrial power and a vast source of fresh manpower. Much of the U.S. contribution to the naval side of the conflict would be in line with the first view, of the United States as the home of mass production. The best-known examples are the floods of merchant ships, intended to make up for losses to U-boats, and of destroyers and subchasers.

Less well known was an imaginative U.S. naval initiative to produce and lay a mine barrier to close off U-boat routes out of the North Sea. The British were already blocking the Strait of Dover with mines and patrol ships. To get at merchant ships approaching western British ports from North America, U-boats had to cross the North Sea and make their way around Scotland. Similarly, U-cruisers had to take this route to reach America’s East Coast, where they attacked in 1918.

The Mine Section of the Navy’s Bureau of Ordnance (BuOrd) submitted the idea for a mine barrage less than two weeks after the United States entered the war. (It also suggested a barrage to close the mouth of the Adriatic, as U-boats operating in the Mediterranean were based in Austro-Hungarian ports there.) Not surprisingly, the proposal attracted considerable skepticism, initially within the U.S. Navy, but in May 1917 the Office of Operations (OpNav) formally suggested the barrage to the British, who found the idea of a 250-mile mine barrier ludicrous. They were finding it difficult enough to close off the much narrower Dover Strait.

BuOrd did not give up and developed an entirely new mine mechanism, the K-pistol. Existing mines exploded when a ship or submarine either broke a glass vial to activate a battery or moved the mine, triggering an inertia pistol. The British and Germans concentrated on horned mines using the vials, which are the type seen so often in movies. BuOrd realized that to cover 250 miles in sufficient depth multiple lines of such contact mines would be needed; otherwise a U-boat could slip over or under a line of mines, avoiding contact. The numbers required were unaffordable—even impossible—to produce in a reasonable time.

The K-pistol used copper wire antennae that streamed high above and below the mine. When a U-boat approached and made contact with an antenna, it and the boat’s steel hull, along with seawater acting as an electrolyte, formed a battery. Current running down the antenna activated the mine exploder. This indirect action allowed an antenna mine—BuOrd’s Mk 6—to cover not only a considerable vertical area but also a sizable horizontal one. In modern terms, the K-pistol was first to exploit the Underwater Electric Potential (UEP) effect. The device brought the 250-mile barrage from the realm of fantasy to bare practicality, but the barrier would still require an enormous number of mines.

U.S. Atlantic Fleet commander Admiral Henry T. Mayo pressed British First Sea Lord Admiral John Jellicoe to support the idea, and he in turn presented it during an Allied naval conference in London in September 1917. One advantage Jellicoe envisioned was that the barrage would be so far from German bases that the enemy could not hope to sweep its mines. When he returned to the United States, Mayo sold the idea to a skeptical OpNav, and Chief of Naval Operations Admiral William S. Benson directed BuOrd to produce 100,000 mines. By this time, BuOrd had designed the K-pistol and a mine case, but going from design to prototype normally would take a year, and producing a massive mine stockpile would require much more time. The Navy had both to build the mines and to create the capacity to lay them. BuOrd had enough faith in the project to let the first contract for 10,000 mines on 9 August 1917, which implies a very quick design process, and award a contract for the remaining 90,000 on 3 October.

The pace of the project suggests that the BuOrd mine section had been pondering the barrage idea for some months before the United States entered World War I; the Navy had certainly formed an antisubmarine section before then. BuOrd seems initially to have viewed the mine barrier as a way of preventing U-boats from reaching the United States, but when the Admiralty reviewed ASW measures for the War Cabinet in January 1918 it pointed to the North Sea barrage as a way of keeping U-boats out of the Atlantic.

To produce mines quickly enough, BuOrd contracted with the U.S. auto industry, the great innovator in mass production. Later the Navy would contract with the Ford Motor Company to produce steel subchasers (“Eagle boats”), but BuOrd was the first Navy agency to exploit this potential.

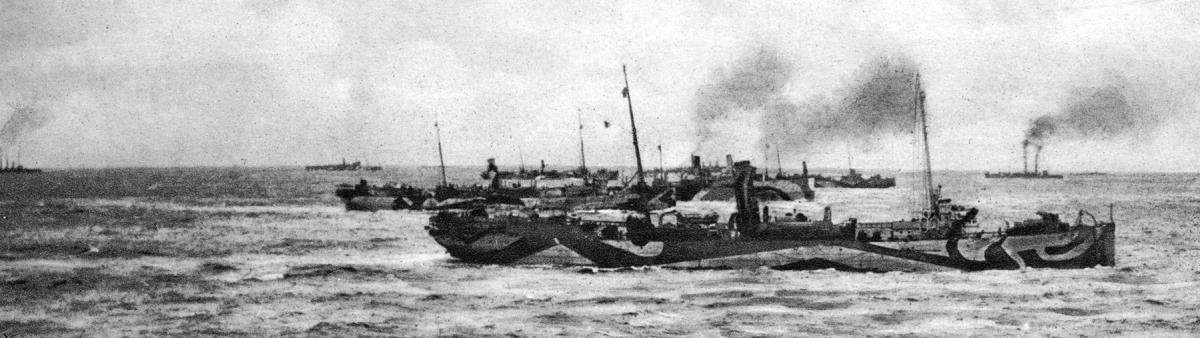

The project moved remarkably quickly, in part because it received the personal support of Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt. Minelaying began in June 1918. The British furnished the necessary bases, but the U.S. Navy used its two cruiser minelayers, the Baltimore (C-3) and San Francisco (C-5), and eight converted ships.

As designed, the barrier stretched more than 280 miles. A patrol force to deal with U-boats trying to cross the barrier on the surface was included in the barrage concept but never assembled. Necessarily, the mine barrier did not extend into neutral Norway’s territorial waters. After it became clear that U-boats were using that open flank to avoid the barrier, the Allies successfully pressed the Norwegians to mine those waters. By the time the Armistice went into effect on 11 November, 56,611 U.S. mines and 13,652 British mines had been laid in the barrage, and the U.S. part of the undertaking was complete except for 6,400 mines (which would have taken ten days to lay).

After the war, the U.S. Navy was eager to learn how effective the barrage had been, both in practice and psychologically; the hope had been that not only would a few U-boats be sunk but some submarine commanders would avoid entering the barrier. Given the limited endurance of a submarine, time spent carefully passing through the barrage on the surface at night would result in less time patrolling in hunting areas. U.S. naval commander in Europe Admiral William S. Sims claimed evidence showed that some U-boat commanders had hesitated before entering the barrage, but that is far from certain. It does appear that barrage mines sank at least six U-boats and severely damaged six more.

The U.S. mining project was born of a potentially disastrous technical problem: surface ships had no reliable way to detect submerged submarines. The one available technique was passive acoustics, but a hunter could not stay in contact once it began depth-charging a sub. Mines were attractive because they solved this problem. It might be necessary to lay tens of thousands to sink very few U-boats, but there were few other options. Conversely, without massive industrial-age production resources, mines were of relatively little value except in very confined waters.

Allied mine technology was extremely poor until 1917, when the British began mass-producing an effective horned mine (the H-6) and the U.S. Navy invented and then mass-produced the Mk 6 mine with its K-pistol. Mining became the most effective single antisubmarine warfare measure. It continued to be important in World War II, but by then active sonar had changed the situation dramatically, and surface and air units destroyed the great bulk of U-boats sunk in that conflict. Thus the great Northern Mine Barrage was very much a creature of its time—and of U.S. industrial power.