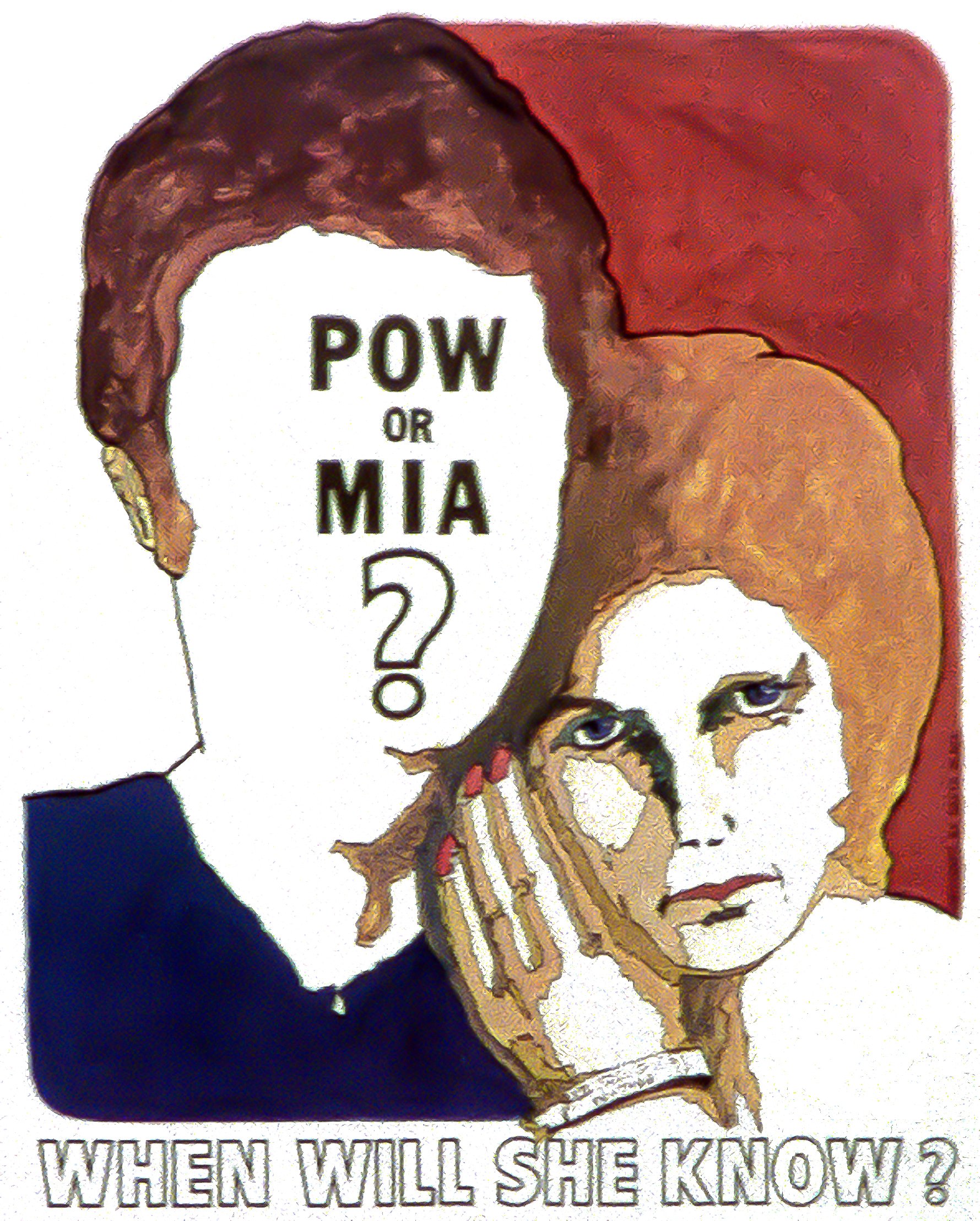

Vietnam POW Interviews

(Volumes I and II)

In 1975, as the Vietnam War was coming to a close with the fall of Saigon, the Naval Institute Oral History Program undertook a project to collect the firsthand accounts of U.S. Navy personnel who had endured imprisonment at the hands of the North Vietnamese during the conflict. From 1975 to 1976, Naval Institute oral historian John T. Mason Jr. took to the field along with Etta Belle Kitchen and Paul B. Ryan to record these memories while they were still fresh in the minds of the former captives. The result was a two-volume anthology filled with vivid recollections in the aftermath of the war — a vital resource for researchers and historians.

Fellowes, John H., Cdr., USN (1932–2010)

Fellowes, a pilot in squadron VA-65, was shot down in August 1966 while flying an A-6A Intruder on a bombing mission from the attack aircraft carrier USS Constellation (CVA-64). His target was Vinh in the panhandle area of North Vietnam. Fellowes' back was broken by the time he was captured on the ground by militiamen. His bombardier-navigator, George Coker, also was captured.

The oral history describes Fellowes's six-and-a-half-year ordeal in North Vietnamese hands and recounts incidents concerning many of his fellow prisoners. He particularly cited the leadership qualities of POWs James Stockdale, Jeremiah Denton, and Robinson Risner. Included is discussion of such issues as the quality of military survival training and the importance of moral development; interrogation and torture; minimum medical treatment; meager food rations; usefulness of cigarettes; physical fitness exercise; camp policies; deaths of other prisoners; communication procedures; entertainment the POWs devised for each other; visits to North Vietnam by war protesters such as Jane Fonda; being paraded in public in Hanoi; the futile Son Tay raid of 1970; B-52 raids on Hanoi; and concerns about his family members back home and limited correspondence with them. Fellowes was released from captivity in early 1973.

The oral history tells of his return, a description supplemented by his article "Operation Homecoming," which appeared in the December 1976 issue of U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings.

Based on two interviews conducted by John T. Mason Jr. in August 1975, Fellowes' portion of the volume contains 278 pages of interview transcript plus an index. The transcript is copyrighted 1976 by the U.S. Naval Institute; the interviewee placed no restrictions on its use.

Stratton, Richard Allen (Dick), Cdr., USN (1931–)

Stratton, a member of squadron VA-192, flew off the attack aircraft carrier USS Ticonderoga (CVA-14) in an A-4E Skyhawk on 5 January 1967. He was on a combination reconnaissance and weather hop when he was shot down that day near Thanh Hoa, North Vietnam. He spent the next six years as a prisoner of the North Vietnamese. From his experiences, he discussed the leadership structure among the prisoners and the North Vietnamese fear of that leadership; the role of officers such as James Stockdale and William Lawrence as leaders; communications methods; interrogation and torture; attempts to get him to defect; the value of religion; descriptions of the guards; the famous incident in which Stratton bowed stiffly to imply he had been drugged before being put on display for the media; his forced confession; the importance of returning with honor; escape attempts; Stratton's assessment of President Lyndon Johnson's handling of the war; the role of neutral countries; U.S. media coverage of POWs; comparison of the POW experience to Elizabeth Kubler-Ross's book On Death and Dying; no early releases were sanctioned except that of Seaman Apprentice Douglas Hegdahl in 1969 to carry prisoners' names back to the United States; and some of the common traits of the American prisoners. Stratton's wife Alice told the story from the family point of view in a July 1978 Proceedings article titled "The Stress of Separation."

Based on one interview conducted by Paul B. Ryan in September 1975. Stratton's portion of the volume contains 144 pages of interview transcript plus an index. The transcript is copyright 1976 by the U.S. Naval Institute; the interviewee's permission is required to cite or quote the material in a published work.

Denton, Jeremiah A. Jr., Rear Adm., USN (Ret.) (1924–2014)

Denton was shot down on 18 July 1965 near Thanh Hoa, North Vietnam, while flying an A-6A Intruder from squadron VA-75, based on the attack aircraft carrier USS Independence (CVA-62). In addition to covering his personal ordeal of torture, he assessed the rationale for the U.S. intervention in Vietnam and the methods employed there; positions of President Richard Nixon and advisor Henry Kissinger on conduct of the war; Communist versus democratic value systems; the Code of Conduct; views on marriage and the family; Communist propaganda; the importance of the command structure among prisoners, led by individuals such as James Stockdale and Robinson Risner; forced confessions; the difficulties of solitary confinement; religious activities in captivity, national security; and speeches to the public following his release.

Denton was the first American prisoner freed in the normal release procedure and thus was called upon to speak to the media when he reached the Philippines in early 1973. The oral history interviews are intended to supplement Denton's book When Hell was in Session.

Alvarez, Everett Jr., Cdr., USN (Ret.) (1937–)

Alvarez was the first U.S. pilot shot down in the Vietnam War. On 5 August 1964 he was lost while flying an A-4C Skyhawk of squadron VA-144 from the attack aircraft carrier USS Constellation (CVA-64). The mission was a retaliation strike on Hon Gay, North Vietnam, for the Gulf of Tonkin incident a few days earlier. In the oral history Alvarez discussed the lack of preparation at that time for rescuing shot-down airmen; injuries sustained in ejection; the makeshift nature of the early captivity; varying attitudes of different guards; initial period of solitary confinement; the Code of Conduct; his belief that visits by American protesters such as Ramsay Clark and Jane Fonda kept the war going; the value of prayer; propaganda and punishment meted out by the enemy; interrogation details; communication with his wife until he learned that she had divorced him; the limited food and medical treatment available; ways in which political events affected the treatment of prisoners; gradual improvement of conditions in the early 1970's; opportunities for sports and exercise; interaction among prisoners; the effect of U.S. B-52 raids on North Vietnam; and eventual release and delivery to the Philippines in early 1973.

The interviews are a supplement to Alvarez's book Chained Eagle.

Based on two interviews conducted by Etta-Belle Kitchen in March 1976, Alvarez's portion of the volume contains 134 pages of interview transcript plus an index and appendix. The transcript is copyright 1977 by the U.S. Naval Institute; the interviewee has removed previous limitations on the use of the material.

Commander Alvarez: Well, we’re military. We are trained to remain as a military unit and through our survival school in a normal POW environment you will maintain yourself as a military unit, so this is the way it is for us. And if you're the senior officer you will take command, just as in the Code of Conduct. Well, anytime we got a group together, whether we were physically together or were just in a building and we could communicate within walls, okay, I'm the senior officer or he’s the senior officer and here’s what we’re going to do. We’re going to follow these policies or we're going to follow the regulations as laid out by the camp senior officer if we happened to have contact with him, or just do the best you can. This kind of thing.

Etta Belle Kitchen: Who was the senior officer? Do you remember who they were at various times?

Commander Alvarez: When?

Etta Belle Kitchen: That's my point. When you were at the Hilton.

Commander Alvarez: Yes, I could name every single senior officer but it changed about every other month. The senior officers of the camps were changed. At the time we were there Robbie Risner was the senior officer until Admiral Stockdale was shot down. He was a commander at the time. He remained the senior officer of all the prisoners. He wasn't with us all the time. General Flynn of the Air Force came in in 1968 and we had other people who happened to be the senior officer in the camp. They would change sometimes almost daily, depending on the situation, depending on how active the Vietnamese were, this type of thing. But we found out.

Etta Belle Kitchen: Can you describe more about how the communications took place? You spoke of writing on the bottom of a tin plate.

Commander Alvarez: That was early stages. That was before we developed the tap code. Once we lived in a building and we were in separate rooms, we could tap from one room to the other. We could keep our line of communications open that way. At other times, we learned to communicate from building to building. We developed the hand alphabet code. You could see someone's hand or else tap the code so it could be heard by someone or other means, covert means, message drops and things like this.

Etta Belle Kitchen: Tell me what you mean. I'm interested in this.

Commander Alvarez: Some things I can't tell you.

Etta Belle Kitchen: Oh, because of some security?

Commander Alvarez: Yes, but, you know, message traffic. We'd leave a note in a message drop or a hand code, hand alphabet, the tap code, or just plain talking, if we could do it. Some way to send signals. If you could get hold of a piece of glass and make a mirror out of it, you could use that.

Etta Belle Kitchen: Building to building?

Commander Alvarez: Right.

Etta Belle Kitchen: What leadership training and disciplinary training in relation to the Code of Conduct had you had before?

Commander Alvarez: Just survival school. That’s general, there wasn’t anything specific. We had to make up and improvise our own method of communication, and we had to improvise our own policies as far as the way to go in this situation. Here's our situation and here’s what we’re going to do.

Etta Belle Kitchen: But you did have training, of course, in the Code of Conduct before you went over there?

Commander Alvarez: Yes, but the Code of Conduct is a very general directive. It’s to give you a guideline. When you're in a specific situation, you have to adapt yourself, you have to adopt a policy or course of action that’s within the guidelines or to the best of your ability. You have to decide, now, is this worth dying for? By God, I don’t think that this is worth dying for, but I’ll resist as much as I can do it.

Etta Belle Kitchen: Did you ever come in a situation where you had to make that decision? Many times?

Commander Alvarez: Yes, several times. When I had to give these propaganda tapes, I said, is this worth dying for? Who in the United States is going to believe this?

Etta Belle Kitchen: And you thought negative?

Commander Alvarez: I thought that nobody in the United States would believe that garbage when they listened to that, but nobody in the United States that I know of hears this, except perhaps some anti-war groups. Actually, what it comes down to is it's not the people in this country, it's for their own people as much as for other people in other parts of the world.

Etta Belle Kitchen: Did the training and the awareness of the Code of Conduct play any part in your interrogations?

Commander Alvarez: Oh, yes, continually. It was always the guideline. This is what you live by or you try to.

Etta Belle Kitchen: Do you think any changes ought to be made in it other than what I guess you perhaps have already said of adjusting to situations as they arise?

Commander Alvarez: I think the code as it exists now does give you the leeway to do that. It does enable you to look at a specific situation and say this is what I think I will do. The code has given me the guidelines and now I can apply myself to this particular problem. The code is under a lot of fire, but I don't think it's justifiably so. I think the code did a lot for us. People say the code didn’t do us any good. It did. It did us a lot of good. In other words, we weren’t able to live up to the code itself, but the code is just a guideline. We were able to live up to an objective that we set. You know, everybody’s different. What it did for us was to enable us to come back and not be ashamed of anything. I don’t have anything I’m sorry for or anything I'm ashamed of. In other words, I’m not going to hide my face from anybody because I did something I shouldn’t have done, because when I did do something I held out as long as I could, and I think that’s all anybody could ask of me and that’s all the code asks of you.

Etta Belle Kitchen: I’m curious to know whether you feel that when they did torture people or threaten them with things of that nature, did that harden their resistance, do you think? Did it actually accomplish anything for them?

Commander Alvarez: Well, everyone’s different, but as for myself I wouldn't say it hardened my resistance, but it hardened me to the point where when I gave in it angered me because they'd made me give in, to the point that when they came again I’d say no again and I’d keep saying no as long as I could. But then others, I think it scared them to the point where they were afraid to say no and it bothered them not to say no because they didn't want to do anything. Others did. It angered them and hardened them. Every person has his own limits and every person has his own reactions.

Psychologically speaking, it was a big psychological game.

Etta Belle Kitchen: The people who came over there, Ramsay Clark, Jane Fonda and their visits and their activities, the release of the Pentagon papers, things of that sort, do you think that had any effect on the length of the war?

Commander Alvarez: Oh, yes, I do.

Etta Belle Kitchen: Do you think you’d have been brought home sooner?

Commander Alvarez: I think that these people who went over there, all these things that happened here, did a lot to keep the Vietnamese going. They had told me before it even started that they were ready to fight a long protracted war, and when they say that they're talking about a war similar to the war they fought against the French, in which they just kept hammering and hammering, but hoping that eventually the French - and in this case we - would become disgusted, discouraged, and turn away, hoping that it would lead to dissension like it did with the French. They told me this before the war even started out there. They started their war with the French in 1945. When it got to the fifties the people of France were tired of this drain and it even caused a change in their government. This is what they had experienced before, so when we got involved this is what they were shooting for.

About Volume I

Based on three interviews conducted by John T. Mason Jr. and P. B. Ryan from August through September 1975, the volume contains 422 pages of interview transcript plus indices. The transcript is copyright 1976 by the U.S. Naval Institute; the interviewees placed no restrictions on its use.

About Volume II

Based on four interviews conducted by John T. Mason Jr. and Etta Belle Kitchen from March through November 1976, the volume contains 281 pages of interview transcript plus indices and appendices. The transcript is copyright 1977 by the U.S. Naval Institute; the interviewees placed no restrictions on its use.