Polaris Program

From 1956, when the U.S. Navy first awarded the development contracts, to 1960, when the first UGM-27 Polaris missile was launched from Cape Canaveral, the Navy was in the thick of a pioneering project that forever would change the way such epic undertakings were approached. The Navy’s first submarine-launched ballistic missile, the Polaris upped the Cold War ante and played a vital strategic role — not only for U.S. forces but in the service of allied fleets as well — through the 1960s and beyond. From 1972 to 1974, U.S. Naval Institute oral historian John T. Mason Jr. interviewed numerous Polaris Program key players, from the CNO to the Secretary of the Navy to the project director to sundry civilians involved in manufacturing the groundbreaking weapon. Collectively, their oral histories recount the inside story of a remarkable technical achievement.

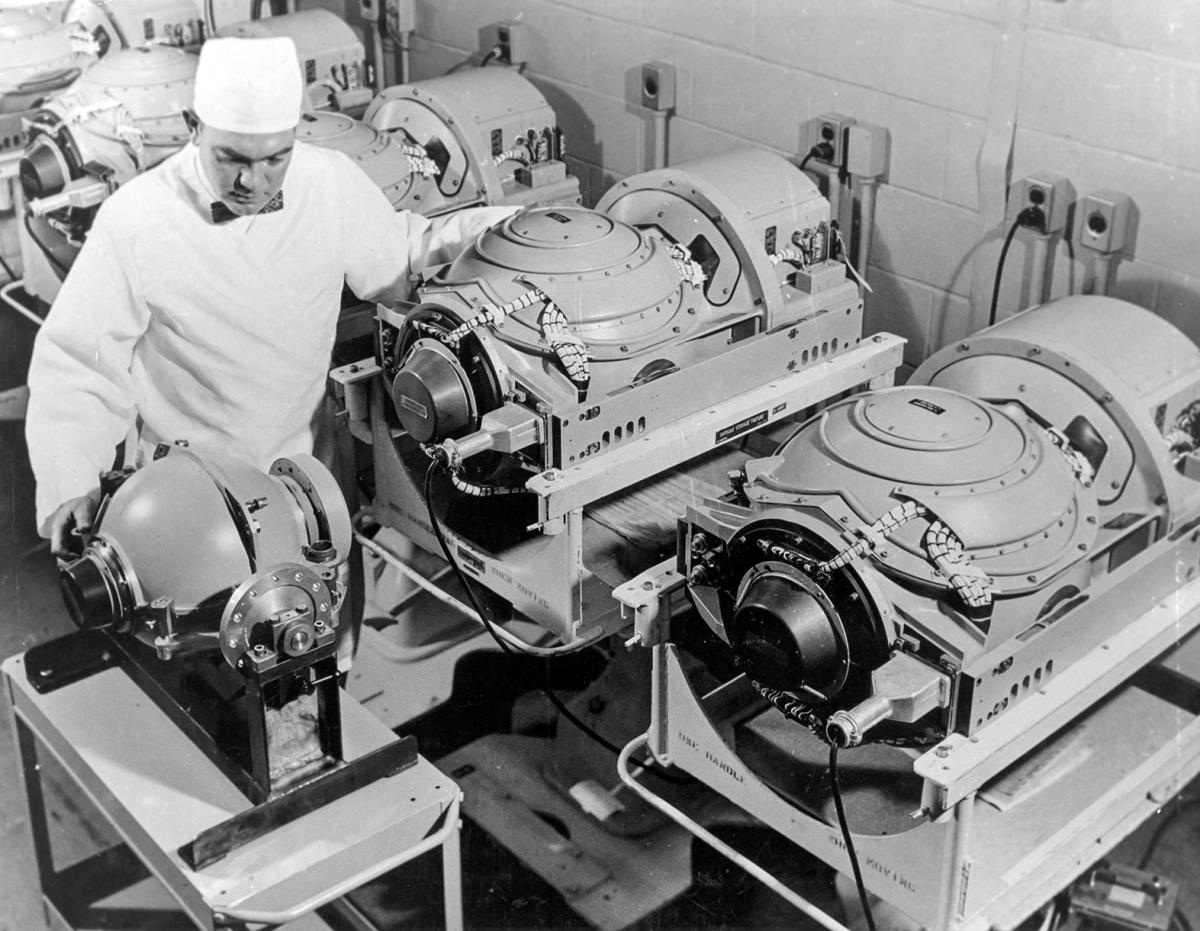

Adm. Raborn Visits the Polaris Assembly Line

In the clip below from his September 1972 oral history interview at his home in Arlington, VA, Admiral Raborn discusses a visit to the assembly line for Polaris SLBM components at the Hughes Aircraft Company.

Admiral Raborn: We wanted to have an alternate supplier for the guidance package, which includes the inertial table and the electronics. So we chose to team Honeywell and Hughes Aircraft. Honeywell was to build the stable table, and Hughes to build electronics. Well, in due time, as was my custom, I made regular tours of the industry team who were making the parts and I went by Hughes and our old friend L. A. “Pat” Hyland — he’s still out there and running a good show — he said, "Would you like to see your work.?" I said, "Sure."

So we went down and there on this very large floor was a Block of about 300 girls working, and they, were in assembly lines making the electronics that were going on this small inertial table in the missile guidance. I noticed as I walked through the line, being escorted by the supervisor, who was a woman, that all the girls at the work. benches were dressed in red, white, and blue middy blouses and skirts, I remarked on this and said, "Why is this that they're all in this patriotic uniform?" And she said, "We're so proud to be a part of the Polaris family that we decided on our own that we’d go buy these and we wear them every Wednesday.”

I said, “Gee, but this is Thursday.” She said "Well, we heard you were coming." "So we wore them to show you how proud we are to be a part of the Polaris program!”

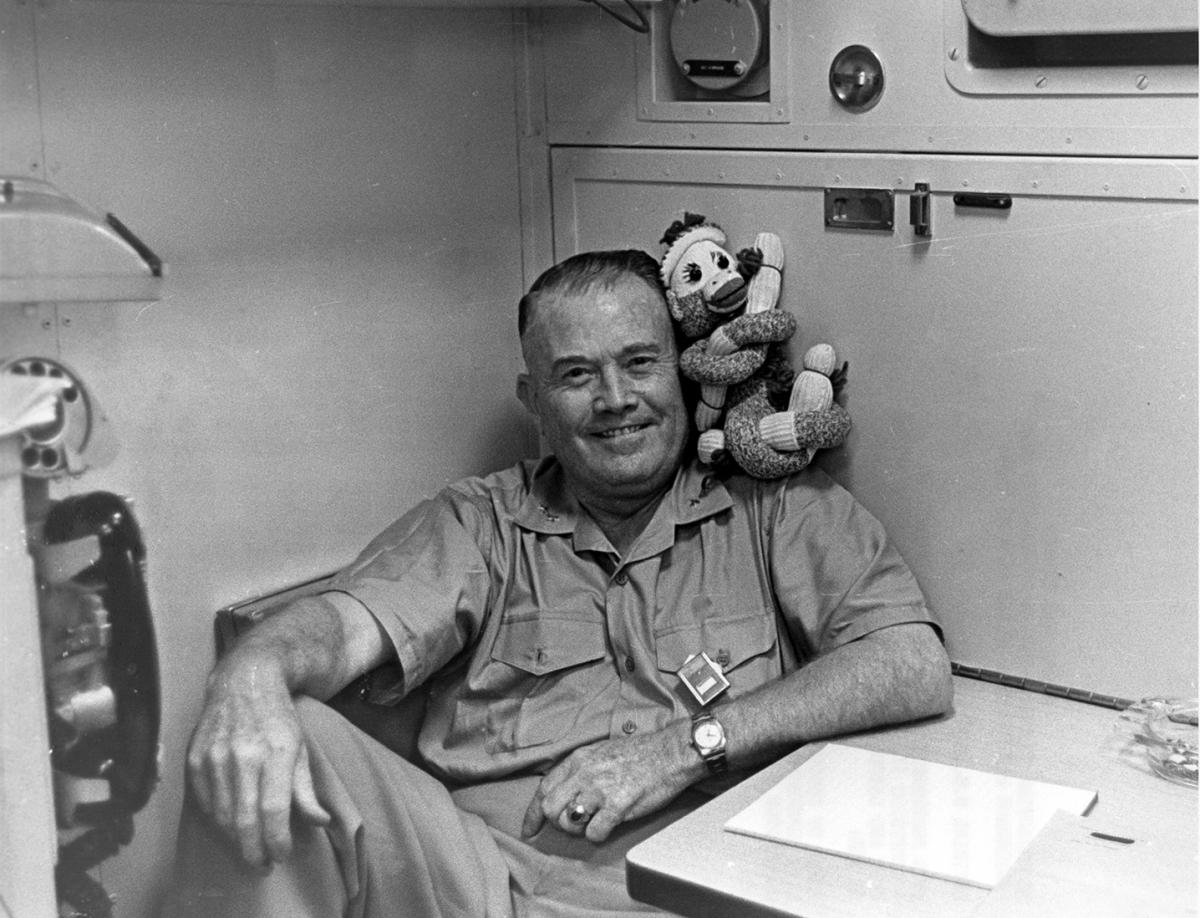

"Red" Raborn on the Adaptation of Man to Machine

Admiral Raborn: [In the Polaris program] it occurred to us that one of the real things that we had to explore and break ground in, was the adaptation of man to the machine. We were going to bring into existence machines and equipment which the Navy had not seen before, and had no experience with. The necessity for the maintainability of the equipment aboard the submarine by the people aboard the submarine and the operability of the equipment by the personnel, was very high on our worry list. We wanted to optimize the knowledge of the people to maintain it and to make the equipment easy to maintain, make it as self-diagnostic for trouble shooting as much as we could. We wanted to make it easily repairable and easily maintainable, because space aboard submarines is quite limited, as you know, and we wanted to put aboard spare parts and replacement parts for the equipment only to the extent absolutely necessary, because we just wouldn't have room for it. Something else had to "give", for everything we put aboard.

"Red" Raborn on the "Magic" Piece of Paper

In this selection, also from his 1972 interview, Admiral Raborn discusses the "magic" piece of paper given to him by Admiral Arleigh Burke in support of the Polaris Program.

Admiral Raborn: It was obvious to everybody that the initial funds would have to come from the existing Navy budget to get started until the new fiscal year came around. I'm sure that this played a major part in the attitudes of the admirals because they could see so many of their cherished programs going down the drain, which were quite important and no one can say that they weren't. It was not selfishness. They had a responsibility for a certain part of the Navy and it was obvious that it was important and proper that they speak up for their part of the Navy.

Doctor Mason: Were you invited to speak your piece at that conference?

Admiral Raborn: At the end of the meeting, as a sort of finale, Admiral Burke turned to me and said, “What do you think?” And, in my youthful enthusiasm, I said that "if the Navy didn't go ahead with it it would be making the biggest mistake it had ever made." With that we were dismissed, and Burke then decreed that we would proceed and proceed with top priority, and wrote a memorandum to that effect. He sent me a copy and it dictated, in effect, that I was to have absolute top priority on anything I wanted to do and everyone in the Navy would be responsive to my requests. If they found that they could not be, they were to come instantly to him with me and he would take it on himself to say no if he thought it was proper.

Obviously, this was a "magic" piece of paper. I carried it in my shirt pocket for days and weeks and months. I only had to show it once or twice and sort of apologetically, you know, the boss has told me to do this. And "gosh, this is something I've just got to do and I hope you understand." Of course, we were given carte blanche on everything, including people that we wanted to come in. We asked that people be ordered in from all over the United States. I got one gent off of a destroyer off the south coast of Africa. He was flown back and put to work.

Raborn, William F. Jr. (Red), Vice Adm., USN (Ret.) (1905–1990)

Director of Special Projects Division to develop Polaris. Raborn discusses the background, personnel, and progress of this project on which he was given carte blanche by CNO Arleigh Burke. Interviewed in September 1972; transcript contains 71 pages.

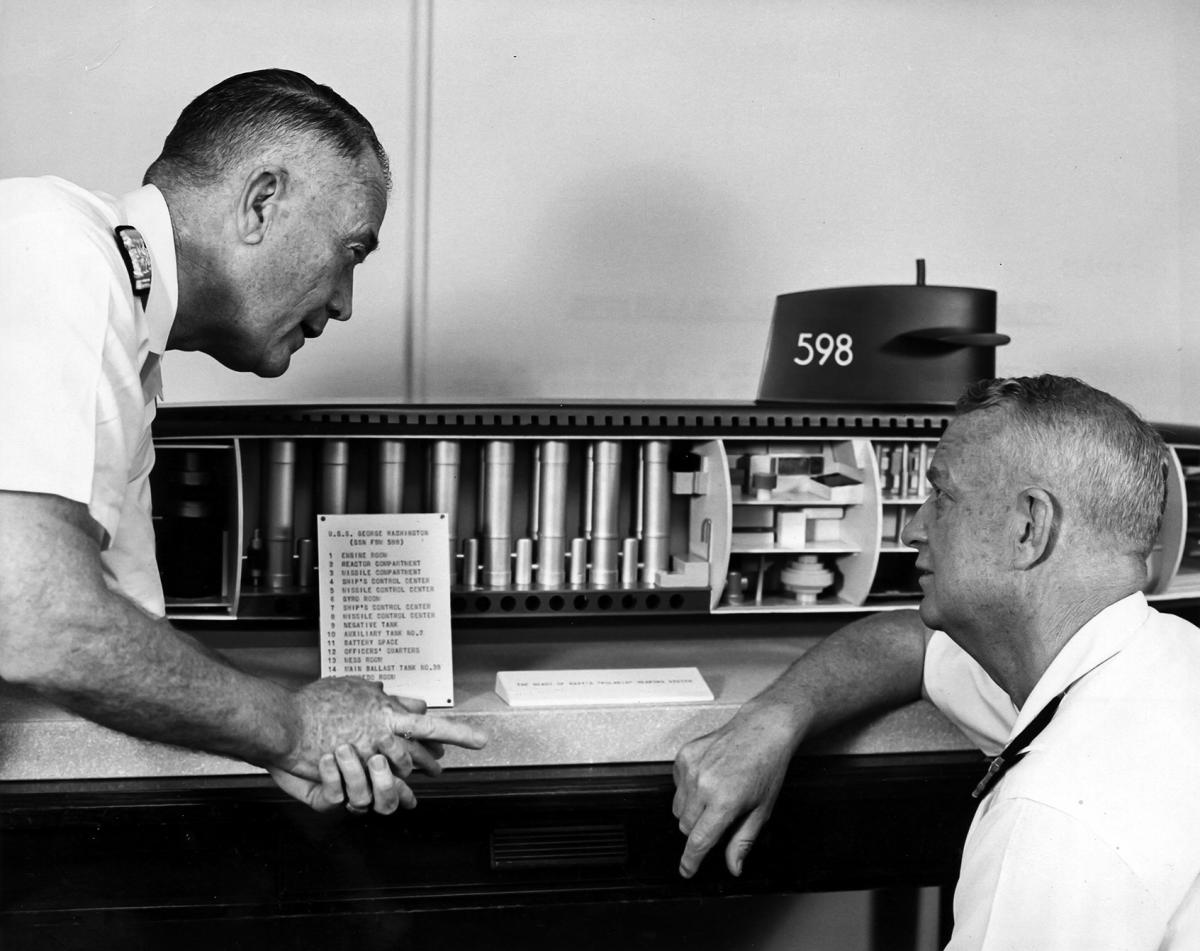

Burke, Arleigh A., Adm., USN (Ret.) (1901–1996)

Chief of Naval Operations, 1955 to 1961. Burke discusses the political overtones surrounding the program, and dismisses the idea that we were racing to develop submarine-launched missiles in response to Soviet advances in that area. Interviewed in September 1972; transcript contains 36 pages.

Gates, Thomas S. Jr. (1906–1983)

Secretary of the Navy from 1957 to 1959. Gates discusses objections to this program that came mostly from within the Navy and the surprising support from the Bureau of Aeronautics. He also covers the safeguards used to ensure a monitoring of the success of the program and proper managing of funds. Interviewed in October 1972; transcript contains 39 pages.

Shugg, Carleton (1899–1992)

Head of Electric Boat Company. Among other facets of the submarine construction aspect of the Polaris project, Shugg talks about security, shipyard logistics, and Admiral Hyman Rickover's role. Interviewed in November 1973; transcript contains 25 pages.

Dunlap, Jack W., Ph.D. (1902–1977)

Member of civilian steering committee for Polaris. Dunlap discusses the background of his selection to this committee, the role of the committee, and its proceedings. Interviewed in October 1972; transcript contains 32 pages.

Pehrson, Gordon O. (1906–1985)

Head of planning staff for Polaris project. Pehrson came to the Polaris program in 1956 as a high-ranking civilian in the Army Department, and describes the bureaucratic aspect of the beginning of the project from a civilian standpoint. His planning group was tasked with laying out program plans for creating the military capability needed for the project. Interviewed in February 1974; transcript contains 66 pages.

Watson, Clement Hayes (1898–1980)

Presentation/public relations contractor for Polaris. Watson was recruited to promote the Polaris project to Congress, the military, and President Dwight Eisenhower. He discusses the strategy used to overcome concerns about engineering feasibility, cost, and the length of time necessary for development. Interviewed in November 1972; transcript contains 65 pages.

About this Volume

Based on seven interviews conducted by Dr. John T. Mason Jr. from September 1972 through February 1974, the volume contains 334 pages of interview transcript. The transcript is copyright 1982 by the U.S. Naval Institute; any restrictions originally placed on the transcripts by the interviewees have since been removed.