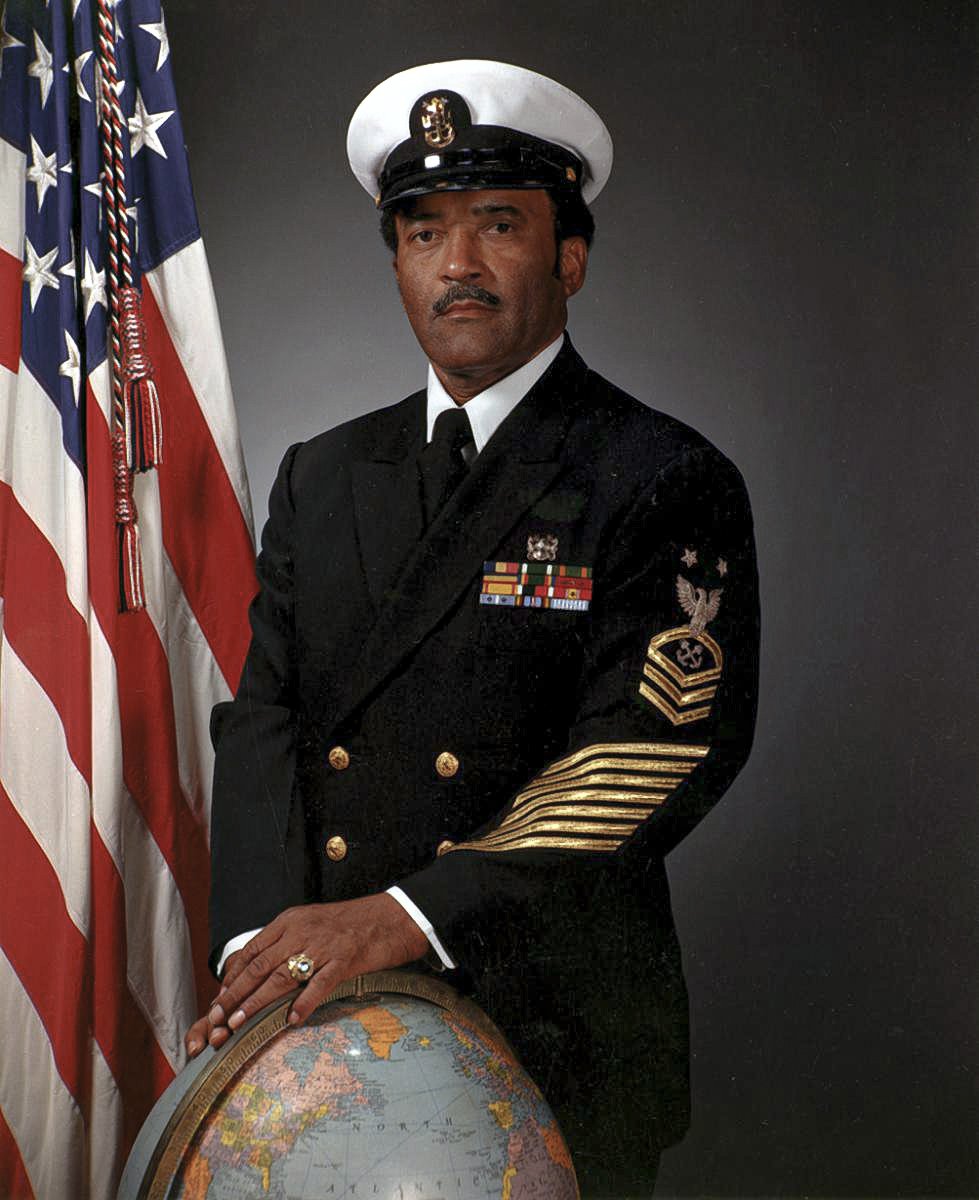

Brashear, Carl M., Master Chief Boatswain's Mate, USN (Ret.)

(1931–2006)

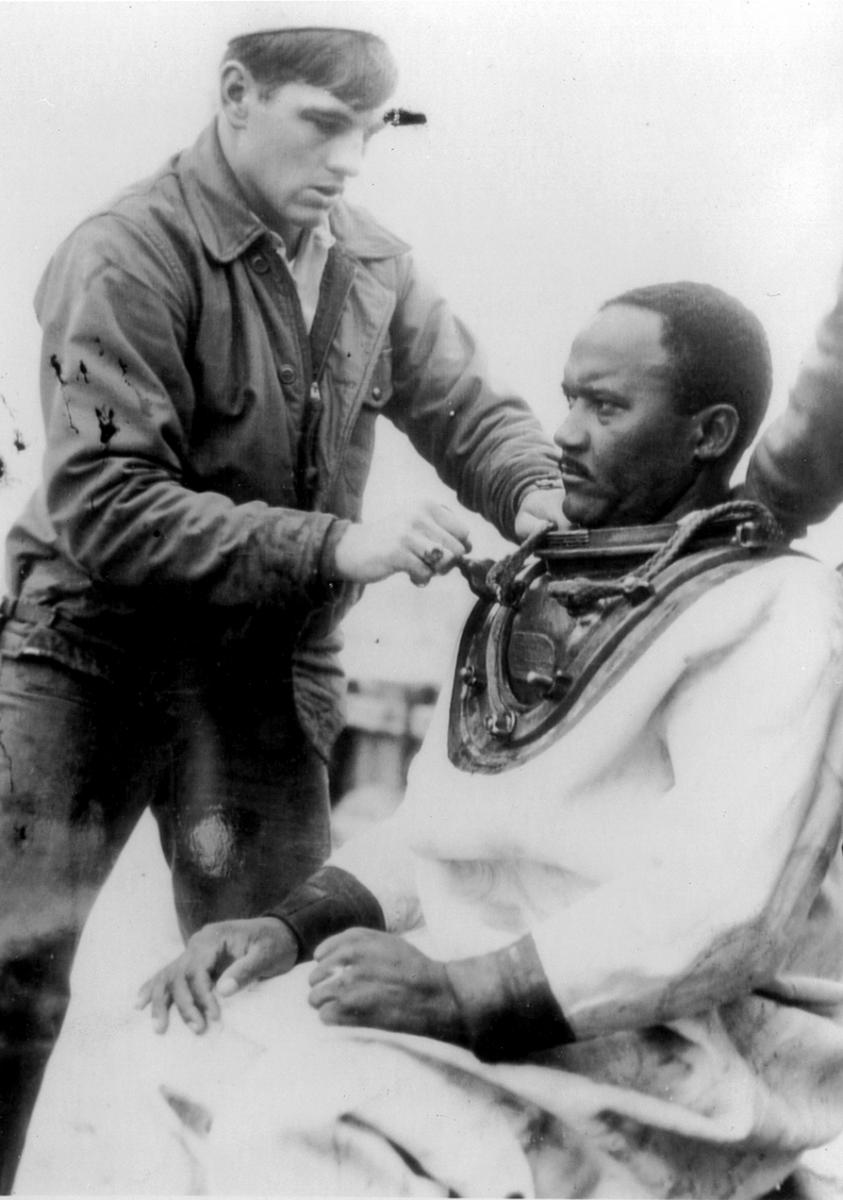

Master Chief Boatswain's Mate Carl Maxie Brashear used a rare combination of grit, determination, and persistence to overcome formidable hurdles to become the first black master diver in the U.S. Navy. His race was an obstacle, as were his origin on a sharecropper's farm in rural Kentucky and the modest amount of education he received there. But these were not his greatest challenges. He was held back by an even bigger factor: In 1966 his left leg was amputated just below the knee because he was badly injured on a salvage operation.

After the amputation, the Navy sought to retire Brashear from active duty, but he refused to submit to the decision. Instead, he secretly returned to diving and produced evidence that he could still excel, despite his injury. Then, in 1970, he qualified as a master diver, a difficult feat under any circumstances and something no black man had accomplished before. By the time of his retirement, he had achieved the highest possible rate—master chief petty officer—for Navy enlisted personnel.

Interview

In this clip from his first interview with Paul Stillwell at Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia, on 17 December 1989, Master Chief Brashear relates the incident that led to the loss of his leg in 1966.

Master Chief Brashear: Well, I got aboard the Hoist [1] and was working and studying and preparing myself to be a master diver. This was when the accident happened and I tore my leg off.

Paul Stillwell: Please describe that.

Master Chief Brashear: Well, in 1966, the Air Force lost a nuclear bomb off the coast of Palomares, Spain.[2] The Air Force asked the Navy to recover that bomb, and, of course, the Navy said yes. Admiral Guest formed the task force, and we started searching for that bomb in January of 1966.[3]

The reason the bomb dropped in the water was that two airplanes were maneuvering, and the fuel plane was fueling a B-52. According to what the people said, it gained on the B-52 too fast, and they collided in midair. Three of the bombs' parachutes opened and landed over on the land in Spain. One of the parachutes didn't open, and it fell in the water. So we searched for the bomb close to the shoreline for about two and a half months, and all we were getting was pings on beer cans, coral heads, and other contacts.

Paul Stillwell: This is with your sonar?

Master Chief Brashear: Yes. But every time we would get a contact, we would dive on it. And we dove around the clock for two months. So the fisherman that saw the bomb go into the water kept telling the officials, "You're too close! Too close! Out there! Out there!" He'd take his fingers and measure. So one day Admiral Guest said we would try it. So they made a replica of the bomb on the tender and then dropped it to see how it would show up on the screen, same dimension, same length, same diameter. Then we went out six miles, and the first pass, there the bomb was, six miles in 2,600 feet of water.

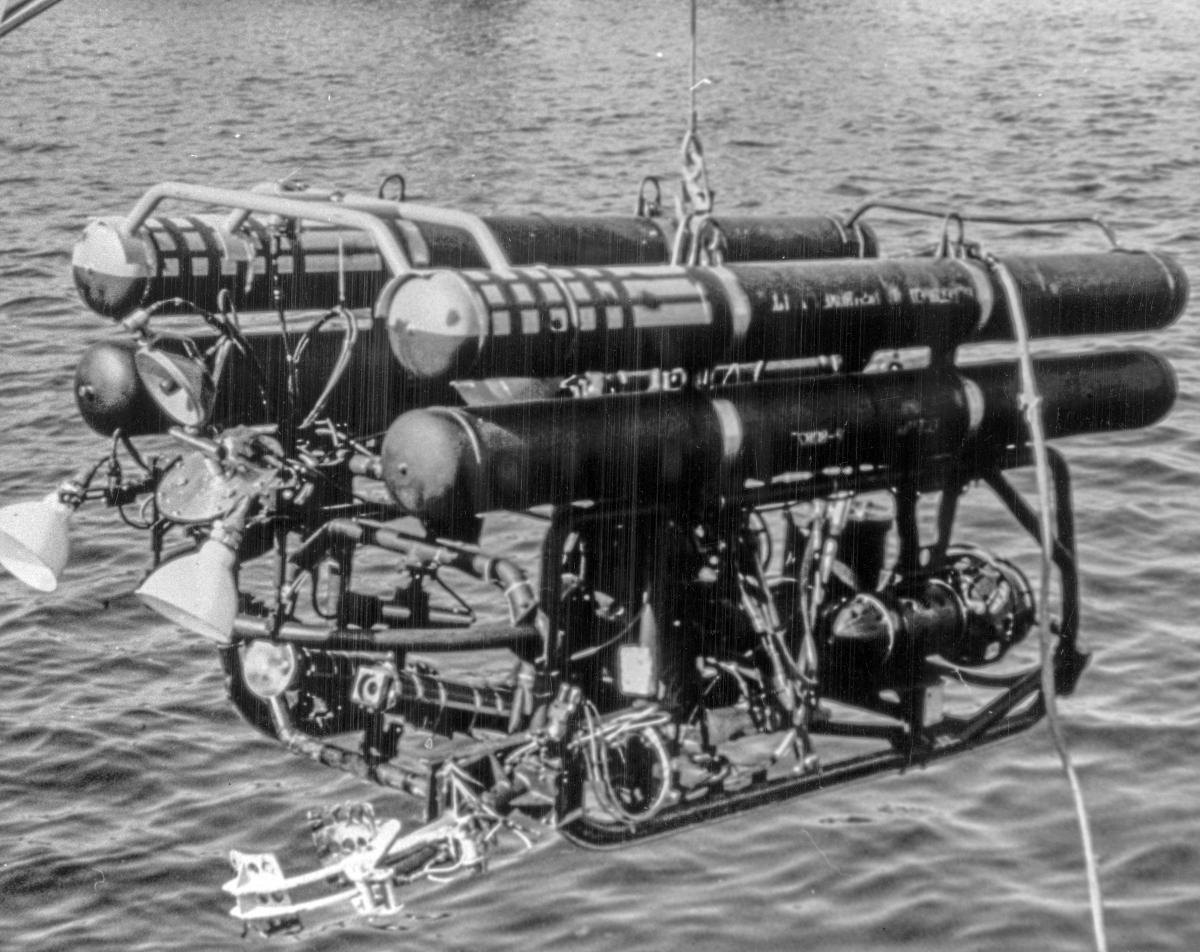

So we rigged to pick this thing up. The CURV, out of Woods Hole was going down to hook this thing up.[4] Stillwell, I rigged up what I call a spider. It was a three-legged contraption that I was going to drop for this bomb to be hooked up to. I had my grapnel hooks and everything, you know. So the Hoist had a very good skipper. Doggone, he was nice!

We dropped that equipment in 2,600 feet of water, and it landed 15 feet from the bomb. The crew of Alvin said it was amazing. The parachute on the bomb hadn't opened, so the Alvin went down and put the parachute shrouds in the grapnel hooks that I had on each leg of the spider. But the Alvin ran out of batteries and had to surface.

So Admiral Guest, through the radio conversation with our skipper, said to pick it up. So we picked it up to a certain depth. Then we brought a boat alongside to pick the crate up out of the boat and set it on the deck to when I picked that bomb up I'd put it in this crate. I was picking the bomb up with the capstan. I got the crate, picking it up, and the boat broke loose. It was a Mike‑8.[5] The engineer was revving up the engines, and it parted the line. I was trying to get my sailors out of the way, and I ran back down to grab a sailor, just manhandling him out of the way. Just as I started to leave, the boat pulled on the pipe that had the mooring line tied to it. That pipe came loose, flew across the deck, and it struck my leg below the knee. They said I was way up in the air just turning flips. I landed about two foot inside of that freeboard. They said if I'd been two foot farther over, I'd have gone over the side. I jumped up and started to run and fell over. That's when I knew how bad my leg was.[6]

[1] The salvage ship USS Hoist (ARS-40) was commissioned 21 July 1945. She was 214 feet long, 39 feet in the beam, had a draft of 14 feet, and a displacement of 1,360 tons. Her top speed was 15 knots.

[2] The collision of the two U.S. Air Force planes was on 17 January 1966. The bomb that fell into the sea near Palomares, Spain, was located by the U.S. Navy's deep-diving research vessel Alvin (DSV-2) on 17 March. Once lines were attached to the bomb, it was brought to the surface on 7 April by the submarine rescue ship USS Petrel (ASR-14). The Hoist took part in the recovery operation.

[3] Rear Admiral William S. Guest, USN.

[4] CURV — controlled underwater recovery vehicle.

[5] LCM-8, a particular model of the landing craft mechanized.

[6] The date of Chief Brashear's accident was 25 March 1966. The lower part of Brashear's leg was not torn off by the accident itself; instead he suffered compound fractures of both bones in the lower leg. A portion of his leg was amputated subsequently on 11 May 1966 because of persistent infection and necrosis.

About this Volume

Based on two interviews conducted by Paul Stillwell in November 1989 and March 1990, this volume contains 164 pages of interview transcript plus a comprehensive index. The transcript is copyright 1998 jointly by Carl Maxie Brashear and the U.S. Naval Institute; the interviewee has placed no restrictions on its use.