Bieri, Bernhard H. Sr., Vice Adm., USN (Ret.)

(1889–1971)

Bieri graduated from the Naval Academy as a passed midshipman in 1911. In the ensuing years to 1919, he served in the USS Delaware (BB-28), Nashville (PG-7), Montana (ACR-13), Virginia (BB-13), and Texas (BB-35). Among his further assignments were duty as aide to Rear Admiral Augustus Fechteler; command of the USS Bailey (DD-269) and Destroyer Division 29; sonic survey of the West Coast in the USS Hull (DD-330); survey of the Alaskan cable from Seattle to Seward; various staff duties; and command of the heavy cruiser USS Chicago (CL-29). He was on the staff of Admiral Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet. After World War II, as a vice admiral, Bieri commanded the Tenth Fleet in the Atlantic and then became Commander U.S. Naval Forces Mediterranean, a forerunner of the Sixth Fleet. He had a tour as Commandant of the 11th Naval District and then was senior naval member on a committee serving the UN Security Council. Vice Admiral Bieri retired in 1951. The final interview in his memoir is devoted to his service with Admiral King.

Excerpt

In this audio excerpt from his oral history, Vice Admiral Bieri describes the naval escort of a trip to Alaska by President and Mrs. Warren G. Harding and other dignitaries in 1923. While Harding was normally pleasant, the vice admiral observed, on this trip, “The President appeared very grumpy.”

Admiral Bieri: If they were, nobody was doing any work on it. We were the only Navy apparently that was doing any of that sort of thing at that time. This survey was completed in April of '23.

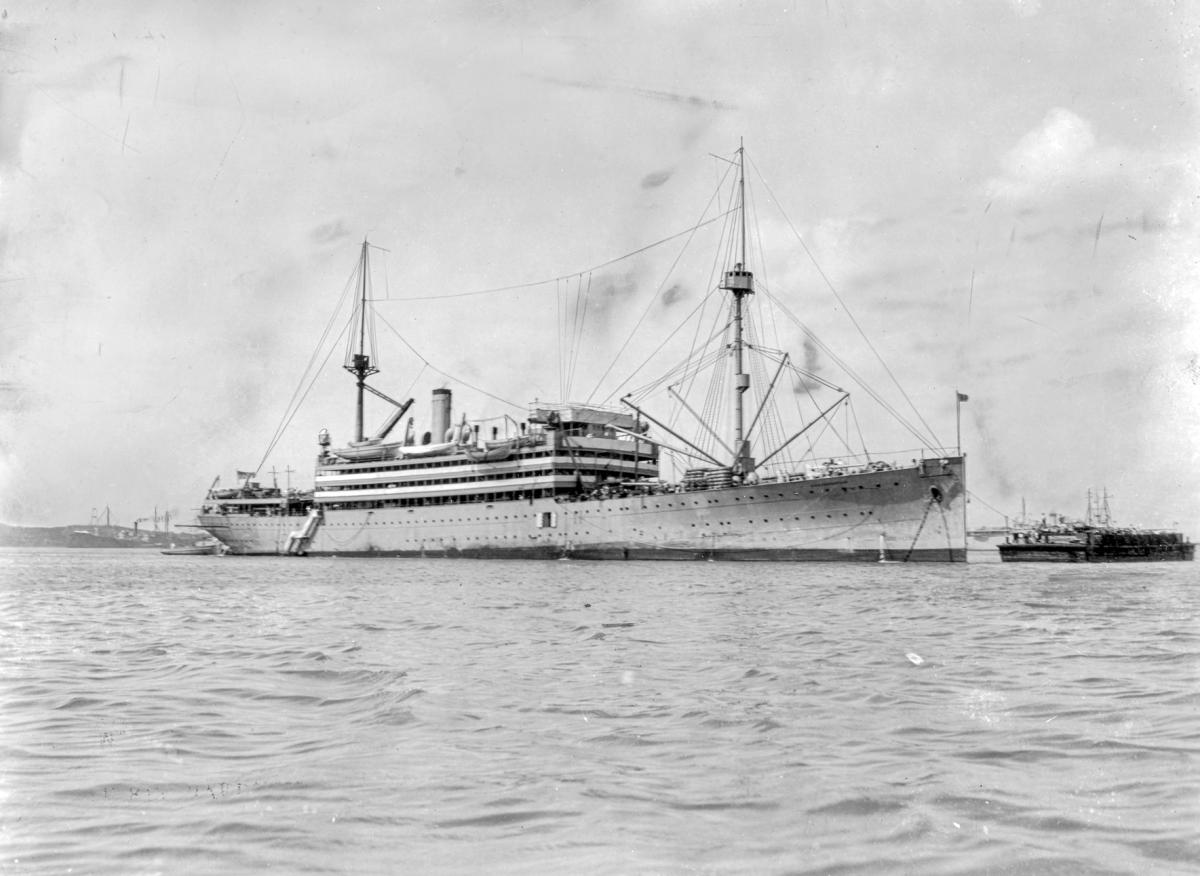

The early summer of that year, the Hull and Corry were detailed to make a trip to Alaska with a convoy carrying President Harding.‡ President Harding, some of his Cabinet, and their families had taken passage on the USS Henderson transport. The two destroyers that were equipped with the sonic range finders were detailed to convoy them to Alaska.

Paul L. Hopper: Was this a protective measure? Or was it also scientific?

Admiral Bieri: In a way, a protective measure, but it was just to have someone with them as escort. We had this sonic range finder so that we could be of use to them if they got into navigational difficulties.

We left Seattle and went up through the inside passage to Alaska. We stopped at all the ports in Alaska: Ketchikan, Juneau, or up and across to Seward. Then we came back through Cordova and stopped at Sitka. Then we turned down the coast again through the inside passage. The President made a visit to Vancouver.

The President's schedule was such that we arrived at all these ports in the early forenoon, as a rule. He would spend a day, and maybe two days in some of them. Then we would proceed again at night to run to the next port. So it got to be rather strenuous cruising for the officers and men on the destroyer.

Paul L. Hopper: Were you invited on board the Henderson at all?

Admiral Bieri: No, I never went on the Henderson. But on our return trip — when we stopped at Sitka on a weekend — President Harding and Mrs. Harding and one or two other couples that were with them came on board the Corry. They inspected the ship, and we had tea for them in the wardroom. The President appeared a little grumpy, but I had previously met the President when I was aide to the commandant at Norfolk and knew his peculiarities to a certain degree.

Paul L. Hopper: Was this a natural state with him, being grumpy?

Admiral Bieri: No, not as a rule. Mrs. Harding was most genial and very nice. I think he probably didn't want to visit any ship and was more interested in getting some sleep or something like that, maybe a game of cards.

We then came on back and stopped at Vancouver. There the Canadian citizens had a parade and a lunch for the President at the principal hotel in town. To this all the officers were invited. The rest of his stay in Vancouver used up the day until about sundown, when we left for Seattle.

Very shortly after we got out of Vancouver and headed south through the sound, we ran into a very, very heavy fog. The captain of the Henderson. Captain Buchanan, ordered the Corry and the Hull to drop astern and to take station one on each quarter.* He was going to proceed at 15 knots, regardless of the fog. In the interval sometime before that, the naval people had ordered out a squadron of destroyers from Seattle to meet the Henderson down at Juan de Fuca Straits and escort her into Seattle for the purpose of making a big show.

The fog continued. We had a Finn on board who was a pilot, and he was supposed to be acquainted with the Alaskan waters and was. We didn't have too much use for him, but we had him along. He came down about 4:00 o'clock in the morning and he heard a fog whistle, almost up ahead. The old pilot said to me, "That sounds like a 10,000-ton ore ship."

I thought to myself, "If that's a 10,000-ton ore ship and the captain of the Henderson doesn't slow down, we're liable to get in trouble with him. And I'm not going to get caught in too much of a mess."

So I took my station at the engineering telegraphs and followed along astern of the Henderson. This whistle continued without change of bearing. All of a sudden, there was a crash. The Henderson had hit one of these destroyers [the USS Zeilin (DD-313)] that had come up from Seattle.

The Hull was apparently also standing by, and we swung onto our engine room telegraphs for full speed astern. We cleared the melee and back in a couple of minutes we were lost in the fog. We didn't know where they were; the general direction was ahead. Then we received a signal from the Henderson that the Corry was to stand by the destroyer. And that the Hull would continue with the Henderson to Seattle.

Paul L. Hopper: Then neither one was badly damaged?

Admiral Bieri: The Henderson was not particularly badly damaged. She hit her bow line, so she just had a dent in her bow more or less.

The destroyer had been hit in the starboard fireroom tanks. She had taken considerable water aboard, she had a hole in her, and she assumed a bad list. By the time we found this destroyer in the fog, she had been abandoned.

Paul L. Hopper: Been abandoned by her crew?

Admiral Bieri: Been abandoned by all the officers and crew. The fog cleared somewhat at that time, but we had no idea what became of the officers and the crew. I had a discussion with my chief engineer. He said, "I think I can go over there with about four or five men. She isn't listing anymore, and she isn't going to sink. I think I can get the steam up on her, and we can steam her in."

I sent this officer over there with four or five men, and he got up steam. We were just about ready to take him in tow as well. The fog cleared off momentarily, and we saw this crew all around the place there in lifeboats and rafts, and so forth. Of course, when they saw us, and saw their ship making some smoke, they all came back on board.

Paul L. Hopper: Had they acted in accordance with Navy regulations in abandoning their ship?

Admiral Bieri: Hardly the best practice. They came back on board. About that time, a second destroyer of that squadron showed up and said he would take the destroyer in tow and take her down to the Navy yard. In the process of doing this, they got their towlines fouled in the destroyer's propeller. It was quite some time before the mess was finally straightened out, and we were able to proceed on our way. The other destroyer took the crippled destroyer in tow and took her to the Navy yard.

Paul L. Hopper: Pre-radar days were strenuous, weren't they?

Admiral Bieri: We went on down to Seattle and joined the part of the fleet that was there.

The President had arrived approximately on time in the early forenoon at Seattle, and they had a big parade for him. Immediately after the parade, he left by train for San Francisco. It was there that he died a day or so later.**

‡ Warren G. Harding was President of the United States from March 1921 until his death on 2 August 1923.

* Captain Allen Buchanan, USN.

** Harding died 2 August 1923.

About this Volume

Based on seven interviews conducted by Dr. John T. Mason Jr. from July through October 1969, the volume contains 257 pages of interview transcript plus an index. The transcript is copyright 1997 by the U.S. Naval Institute; the interviewee placed no restrictions on its use. This is a revised version of the original oral history, which was issued in 1970. The new version has been completely retyped, annotated with footnotes, and given a detailed index.