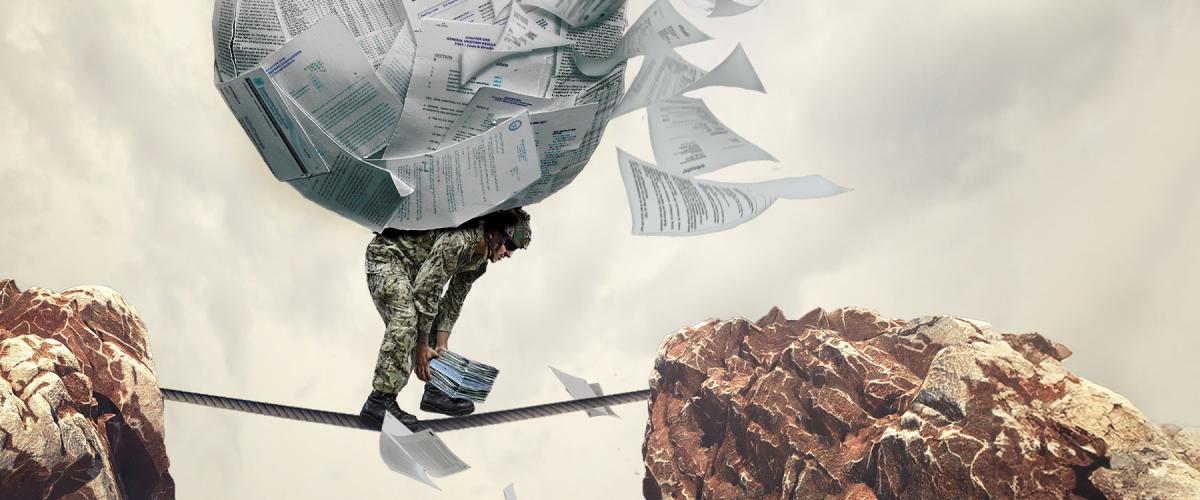

Today, service members may find themselves in situations in which they disregard or violate a regulation, order, or directive.1 Because of an overwhelming number of requirements, they sometimes must choose which ones to follow—or may not realize there is one they should be following. This not only normalizes deviation from the requirement that is unmet, but also inculcates a culture in which it is common to “work around” requirements if they are perceived as unnecessary or extraneous. In a military that prides itself on discipline and standards, this could be catastrophic to good order and discipline and degrade warfighting capabilities.

A Regulation Explosion

Imagine a destroyer at sea. She has been operating nearly continuously at high tempo. Some of the radar controls in the combat information center (CIC) are not working. This is somewhat immaterial, however, because the operators do not know how to use them properly. The CIC is strewn with trash. There are routine violations of standing orders on the bridge. This obviously is a suboptimal situation for a warship at sea.

But this is not a hypothetical scenario. It was described precisely this way in an initial investigation of the 2017 USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62) collision as reported by Navy Times.2 Did the crew neglect their assigned tasks because they were lazy or wanted the ship to fail? Almost certainly not. They lacked training, were fatigued, and lived in an environment where “cutting corners” and deviating from defined standards had become normal.3

The Navy’s Comprehensive Review and Strategic Readiness Review noted that service culture had normalized deviation from standards—a systemic problem arising from an excessive number of requirements. Indeed, every day within the military, individuals can violate established requirements without even knowing it.

The problem is far from solely military. In 2008, legal scholar Douglas Husak described more than 3,000 crimes scattered among the federal criminal code and other statutes and estimated that more than 70 percent of U.S. adults likely had committed a federal crime that could lead to imprisonment without realizing it.4

But it is a more critical issue for the military. Leaders often draw a direct line from basic discipline to combat effectiveness. If discipline is the “instant and willing obedience to orders,” as former Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps Troy Black defined it in 2021, the logical corollary is that an environment or a culture that encourages unwitting disobedience, neglect, or disregard of orders is corrosive and problematic for combat effectiveness.5

Accidental Deviance

In the military, the number of specific requirements to which service members are subject is probably beyond their capacity to manage or fully understand. For example, the Marine Corps Publication Electronic Library includes more than 5,000 unique documents, each with any number of discrete requirements, and the service releases approximately 700 Marine Administrative Messages every year, while canceling only around 20. Navy messages generally are fewer, but there are thousands of Chief of Naval Operations instructions, Secretary of the Navy instructions, and other such documents in the unclassified realm—each often including multiple tasks and requirements that apply to broad swaths of the service. Some are tightly focused but can have ripple effects beyond their specific communities.

In addition, there are at least hundreds of joint, interservice, and Department of Defense (DoD) requirements. And each echelon of command or staff tends to generate its own, many of which are additive. Layered on all these are cultural norms that are rarely specified in a directive yet carry the same force. For example, Marine Corps regulations do not specifically state that a male Marine must have a fresh haircut each week. Nonetheless, Marines are treated as “deviant” if they arrive to work on Monday without one.

Service members are likely to focus on trying to understand and adhere to those requirements most germane to their daily lives. Some might suggest this means the system is working as designed: Those most likely to interact with a given requirement are those most likely to know its specifics. The Naval Air Training and Operating Procedures Standardization program instructions, for example, will be familiar to aviation personnel but likely not submariners, and the regulations governing drill and ceremonies generally have little relevance for a public affairs officer. Nevertheless, the number of basic requirements each Marine or sailor is expected to know and obey is far too many to manage. And if they encounter a situation in which an order that previously did not matter to them now applies, the expectation is that they adhere to it—whether or not they know it exists.In practice, service members likely violate a multitude of requirements every day.6

Different requirements also can layer and interact in unforeseen ways. A salient one comes from the COVID-19 pandemic. Each echelon of command published its own guidance on required protective measures, while different portions of the bureaucracy continued to publish and update guidance based on their own changing knowledge and emerging understanding of the pandemic. Rarely, however, did the guidance at different echelons change simultaneously, so published requirements often contradicted each other.

With the rapidly changing guidance, leaders who had neither the time nor wherewithal to research every policy document produced by DoD, the joint force, the service, the Defense Health Agency, and other portions of the chain of command almost certainly knew they were violating some order somewhere yet had no ability or desire to figure out what it was. Most thus focused on only the most immediate and seemingly germane.7

In the worst instances, this sort of ignorance can have tragic results. Accidental deviation in safety incidents is all too common throughout the services.8

Deliberate Deviance

Far more pernicious than accidental deviance is falsifying or simply disregarding known requirements. Multiple Navy investigations after the Fitzgerald and John S. McCain (DDG-56) collisions noted regular and accepted deviation at all echelons of command. From the fleet commander to the individual sailor, service members “cut corners” and knowingly accepted additional risk to complete the assigned mission. Knowing the standard, knowing it is unachievable, yet still “finding a way” normalizes the idea that standards are malleable and can be circumvented when necessary to accomplish the mission.

A simple example of the “deliberate deviation” phenomenon is the Marine Corps regulation regarding what socks to wear with the Marine Corps Combat Utility Uniform. Until 23 March 2022, only “coyote brown” socks were authorized. Few Marines spent any time or effort adhering to this regulation. The change to allow different color socks simply recognized the truth of the situation: The regulation was neither useful nor enforceable, and Marines regularly ignored it. But ignoring even such a simple regulation can degrade military discipline by normalizing deviance.

A more egregious example is the Navy’s “Fat Leonard” scandal. While the blatant criminality here is qualitatively different from wearing the wrong color socks—those involved with Fat Leonard violated the law and put their own well-being above that of the Navy—the underlying issue is the same, just taken to an extreme. It is certainly possible that all these officers were just “bad apples,” but it is at least as likely that they became inured to deviance by cutting corners and disregarding regulations that seemed unnecessary and thus grew accustomed to thinking all rules and regulations were malleable. In this example, there also were surely others who had an inkling of something wrong but opted to disregard the steady accumulation of such indicators.

Normalize Adherence

In the name of discipline and predictability, the services seek to regulate everything from social media posts to large-scale troop movements. Were service members to attempt to obey every rule and regulation, they in all likelihood would have time for nothing else. However, every time a service member declines to follow a requirement—even wearing a different color sock than authorized—they contribute to the normalization of deviant behavior. Each time a fleet, corps, or component commander knowingly or unknowingly deviates from established service or joint requirements, they do the same.

There are of course times when one must deliberately disregard the rules. But if those instances become the norm and not the exception, the military will have a problem.

The solution is not to add more regulations or try to enforce adherence to all existing ones. Not merely counterproductive, overregulation becomes detrimental when members are unable to meet the requirements and just stop doing them. Instead, the best solution would be to reduce the number of requirements on service members, removing as many irrelevant or unnecessary ones as possible.9 Provide broad guidance, incentivize adherence to its spirit, and build a culture that normalizes adherence to discipline, accountability, and the inherent desire to do the right thing.

1. There are a number of different terms for the rules inherent in military life: policies, directives, orders, regulations, etc. While recognizing there are important differences among them, this paper uses “requirements” as a blanket term. The definition used for “deviant behavior” is behavior that “does not conform to norms and roles.” See Stuart Palmer and John A. Humphrey, Deviant Behavior: Patterns, Sources, and Control (New York: Springer Science + Business Media, 1990), 3

2. Geoff Ziezulewicz, “Worse than You Thought: Inside the Secret Fitzgerald Probe the Navy Doesn’t Want You to Read,” Navy Times, 13 January 2019.

3. Hon. Michael Bayer and ADM Gary Roughead, USN (Ret.), Strategic Readiness Review (Washington, DC: U.S. Navy, 3 December 2017), 22; and VADM Joseph Aucoin, USN (Ret.), “It’s Not Just the Forward Deployed,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 144, no. 4 (June 2018).

4. Douglas Husak, Overcriminalization: The Limits of the Criminal Law (New York: Oxford Academic, 2008), 25.

5. SgtMaj Troy E. Black, USMC, “Non-Negotiables,” Marine Corps Gazette 105, no. 1 (January 2021).

6. One common example is in requirements with periodicity built in. For example, every year when the fiscal year changes, thousands of Marines and sailors are no longer compliant with cybersecurity rules, yet they continue to access the services’ networks.

7. For an example of “requirement layering,” see “Complete Command Probe into USS Theodore Roosevelt COVID-19 Outbreak,” USNI News, 17 September 2020 (page 22 of report).

8. For example, see Government Accountability Office, Military Vehicles: Army and Marine Corps Should Take Additional Actions to Mitigate and Prevent Training Accidents (Washington, DC: GAO, July 2021); and National Commission on Military Aviation Safety, “Report to the President and Congress of the United States,” 1 December 2020.

9. See LtCol Thaddeus Drake Jr., USMC, “Trust Decay,” Marine Corps Gazette 106, no. 6 (June 2022): 65.