In the early hours of Thursday, 11 January, the United States and several partner nations struck targets in Yemen in response to Houthi missile and drone attacks on merchant and naval shipping in the Red Sea. The Houthis’ attacks are not only a gross violation of freedom of navigation, but their chilling effect on the willingness of shipping companies to transit the Red Sea could negatively impact an already fragile global economy if allowed to continue.

Why conduct these strikes? Such action will always be guided by the internationally recognized legal stricture of necessity. The strikes were determined to be necessary to restore freedom of navigation on one of the globe’s most important waterways. After numerous warnings, these partners clearly felt it was time to act to restore deterrence against the Houthis, who, with Iranian support, claim to be acting in protest of Israeli action in Gaza. Defensive actions at sea—including expending numerous costly surface-to-air missiles to defend against relatively inexpensive missiles and drones—were deemed inadequate to deter the threat to shipping any longer.

Why Strike Now? While everything is politicized in Washington, D.C., there are several appropriate reasons why the Biden administration waited as long as it did to bring this action together.

First, time was required to gather the coalition, produce the required intelligence on the correct targets, and coordinate the strike among the many players. Second, it was deemed important to give time for the Houthis to heed warnings for the United States and its partners to reach the standard of necessity and to achieve the moral high ground. Though under international law United Nations (UN) approval was not necessary in this case, because the coalition was acting in collective self-defense, it was useful to gain at least a condemnation of the Houthi action by the Security Council. This was achieved via an 11-0 vote on 10 January, with four nations, including veto-wielding Russia and China, abstaining.

Finally, the administration is attempting to prevent increased general instability in the Middle East from escalating into more open conflict and preferred to use offensive force only as a last resort. The final straw in necessity was the large Houthi attack conducted earlier this week, including against coalition military ships.

Who was involved? The U.S.-led coalition of nations includes the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Australia, Canada, and Bahrain. Building a coalition to conduct such an operation involves several variables and questions: Which nations have been affected by Houthi action? Which nations can provide strike or other assets? Which nations are willing to have their support attributed?

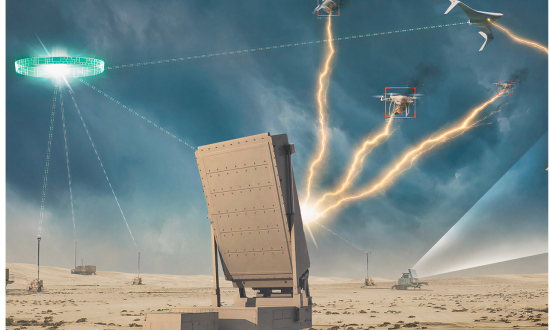

How was the strike conducted? The operation was likely orchestrated by U.S. Central Command’s Combined Air Operations Center based in the region. As USNI News reported, 60 targets were struck in 16 locations. Because such actions will always be conducted under the additional law-of-war stricture of proportionality, targets only included facilities most directly associated with Houthi offensive actions, as well as defensive systems that could impede coalition freedom of action. These included Houthi weapon magazines, command-and-control facilities, surveillance systems covering the Red Sea, surface-to-air systems, and areas from which the attacks were launched.

Targets and timing were likely also selected to minimize loss of life, especially collateral damage. The Houthi announcement that the strikes killed five fighters and wounded six seems to indicate that this consideration was successful.

A wide variety of strike systems allowed the burden of and responsibility for action to be shared among the various coalition partners. F/A-18 Super Hornet strike fighters from the the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69) and aircraft from the U.S. Air Force were involved, as well as Royal Air Force Typhoon fighters based in Cyprus. Interestingly, submarine- and surface-launched Tomahawk land-attack missiles were employed as well, perhaps to assist electronic warfare assets (such as the EA-18G Growler) in ensuring the safety of crewed aircraft against any Iranian-supplied surface-to-air missile systems possessed by Houthi forces.

What comes next? The Department of Defense is reporting an initial assessment that the strikes had good effect. However, because of the face-saving nature of regional culture, it is unlikely the Houthis will completely cease their attacks on shipping in the Red Sea, although their capability to do so has undoubtedly been diminished. Indeed, the Houthis defiantly announced in the wake of the strikes that they will continue to attack shipping in the Red Sea. More missile and unmanned air systems are likely hidden in Yemen’s mountainous regions, and Iran will surely attempt to resupply Houthi forces. So, more strikes may be necessary, although the coalition will not want to settle into a long-term operational rhythm.

Concerns have existed for decades regarding the vulnerability of the Red Sea as a choke point for global trade, particularly the narrow Bab-al-Mandab Strait at its southern end. (I commanded an amphibious transport dock there in the late 1990s in support of a potential evacuation of Eritrea, and we were constantly on alert for potential interdiction from both sides of the Strait, even in those relatively peaceful days.) Through their actions and the coalition response, the Houthis in Yemen have now catapulted themselves onto the world’s front pages. This ongoing skirmish only highlights the utility and importance of naval and air forces in maintaining freedom of navigation around the world.