In October 2023, the Supreme Court ended the practice of race-conscious admissions in public and private universities with its ruling in Students for Fair Admission (SFFA) v. Harvard and SFFA v. University of North Carolina (UNC). The court found that race-conscious college admissions practices, otherwise known as “affirmative action,” violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution. The Supreme Court concluded that, “Both [Harvard and UNC] lack sufficiently focused and measurable objective warranting the use of race, unavoidably employ race in a negative manner, involve racial stereotyping, and lack meaningful end points.” The court made one loud exemption in a footnote, writing, “this opinion does not address the issue, in light of the potentially distinct interests that military academies may present.” While race-conscious admissions practices have ended in civilian higher education, a footnote allows them to persist in the service academies.

Also in October 2023, the same advocacy group that brought the cases against Harvard and UNC filed similar suits against West Point and the U.S. Naval Academy, highlighting the academies’ persistent use of race-conscious admissions. These cases were brought in the Southern District of New York and the District of Maryland and would have to be appealed through the circuit courts before reaching the Supreme Court. However, they once again raise the question of whether the military service academies are prepared for race-neutral admissions.

Last year, I wrote that the service academies should be prepared for the end of affirmative action. While the holdings in SFFA v. Harvard and UNC do not affect the service academies’ admissions practices, the decisions should be a bellwether for the direction of legal jurisprudence about race-conscious admissions. In its footnote, the Supreme Court hinted that the military academies would be held to a different standard as the government’s interest in national security is both inherently compelling and deserving of a degree of judicial deference. However, a clear Supreme Court test can predict how Naval Academy admissions practices will be reviewed in the present case against it.

The SFFA v. Harvard Test

In SFFA v. Harvard, the Supreme Court establishes a clear test of whether race-conscious admissions pass the “strict scrutiny” standard necessary to justify deviation from the Equal Protection Clause. The strict scrutiny standard asks whether the racial classification is used to further compelling government interests and is narrowly tailored enough (i.e., necessary to achieve that compelling interest).

First, the Supreme Court required that any use of racial classification must have focused and measurable objectives. In other words, the government must state its compelling interests in a measurable way.

Second, the Supreme Court required that even if there is a compelling interest, the use of racial classifications cannot employ race in a negative manner (e.g., disadvantage any person because of their race) or involve racial stereotyping (e.g., assuming someone will have particular attributes because of their race alone.)

Third, and somewhat uniquely, the Supreme Court required the use of racial classification have a logical end point, after which racial classifications would no longer be necessary.

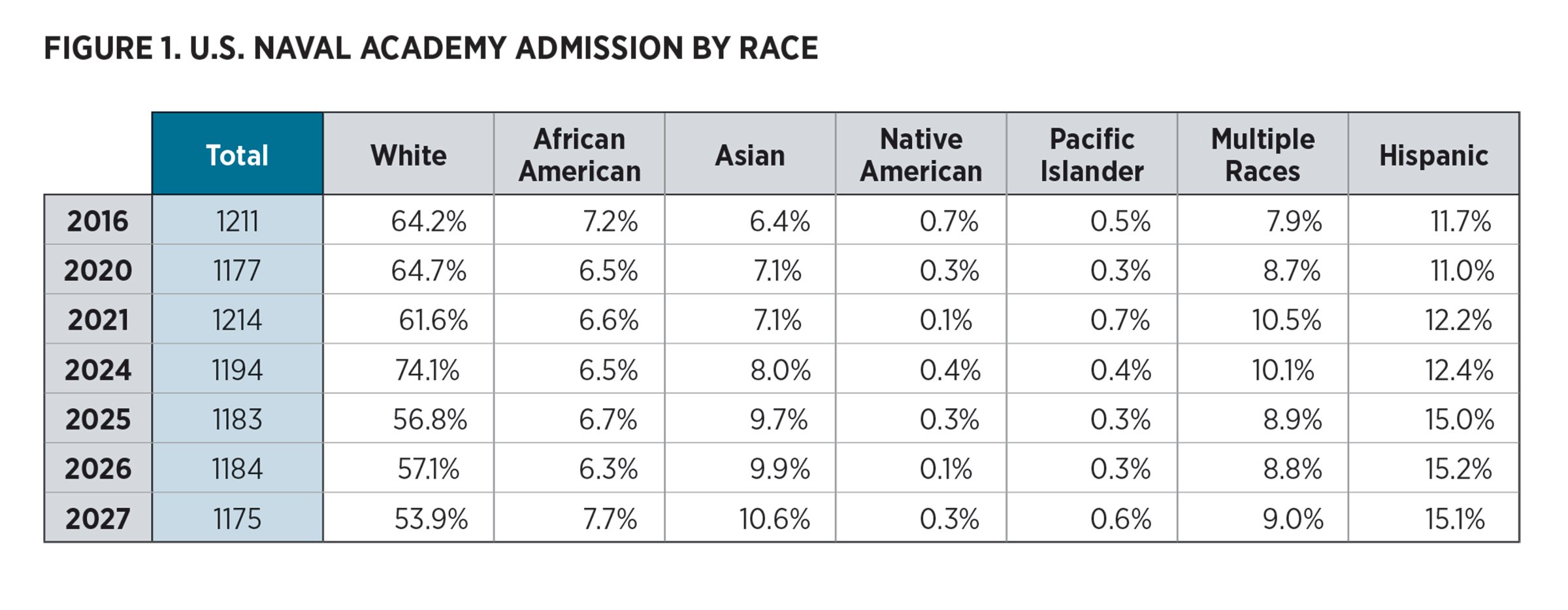

The Naval Academy uses race as a factor when admitting students. It does not use quotas, but rather uses race in a holistic manner. However, the Academy’s holistic consideration of race produces notably stable admission rates by race. See Figure 1.

To pass the SFFA v. Harvard test, the Naval Academy must show that the use of racial classification in admissions has focused and measurable objectives. The objectives of racial classification in service academy admissions differs from those of civilian universities. In a brief submitted to the Supreme Court, former Naval Academy superintendents, and other generals and admirals argued that racial classifications are necessary because the racial composition of the military officer corps needs to reflect the racial composition of its enlisted corps. In another brief, they also argued that the military has a powerful interest in developing an officer corps that is prepared to lead a diverse force and that shares the racial diversity of the enlisted ranks. Both interests are founded in the belief that equivalent racial composition among officer and enlisted populations are necessary to preserve unit cohesion and reduce racial tension. Alternatively, this group has argued that race-conscious admissions and other selection practices makes the Navy more effective at accomplishing its mission.

Seeking to match the racial composition of the officer population to the enlisted population is a clear and measurable objective. However, that objective is not clearly tied to a compelling government interest in either promoting trust between officer and enlisted member populations or to accomplishing the Navy’s mission. Implying that trust between enlisted member and officer populations can only be achieved with racial parity invokes a stereotype that enlisted service members form opinions of their peers and officers primarily based on an assessment of race rather than in terms of character or competency. Furthermore, the proposition of balancing the racial profiles of both populations implies that the Naval Academy will require the use of racial classifications in perpetuity. Despite these weaknesses, the court may nonetheless give it a degree of deference as it often does to matters of national security.

However, even if the Naval Academy gets deference because of its proximity to matters of national security, it will have a difficult time showing that these racial classifications do not disadvantage applicants based on race or involve racial stereotyping. In SFFA v. Harvard, the Supreme Court was clear that “college admissions are zero-sum.” It clarified that, “a benefit provided to some applicants but not to others necessarily advantages the former group at the expense of the latter.” Given this unequivocal statement, it will be hard to argue that race-conscious admissions that provide advantages to applicants of certain racial minorities do not disadvantage other applicants.

Looking Forward

Given these factors, the Naval Academy does not appear to have a strong case to continue to use racial classifications. However, the Academy may continue to argue that race conscious admissions practices are necessary to maintain national security and ask the courts to defer to the military’s expertise. With the rest of civilian academia moving away from race-conscious admissions and with public sentiment overwhelmingly in support of race-neutral admissions practices, the military academies will be outliers.

Beyond the service academies, these cases should prompt military leaders to consider how racial classifications are used in all facets of military recruiting and retention. If race-conscious admissions practices end at the service academies, the next question may be whether the military is prepared for race-neutral recruiting.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Marine Corps, Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.