The Coast Guard should consider rebranding its districts to better connect with and represent the people and regions they serve.

Few inside or outside the Coast Guard understand the current numbered naming convention. It originally was designed to align with Navy districts.1 With the passage of the Goldwater-Nichols Act in the 1980s, however, the Navy phased out its district system, and by 1999, there were no Navy districts to align with, yet, the Coast Guard remains wedded to the number system.

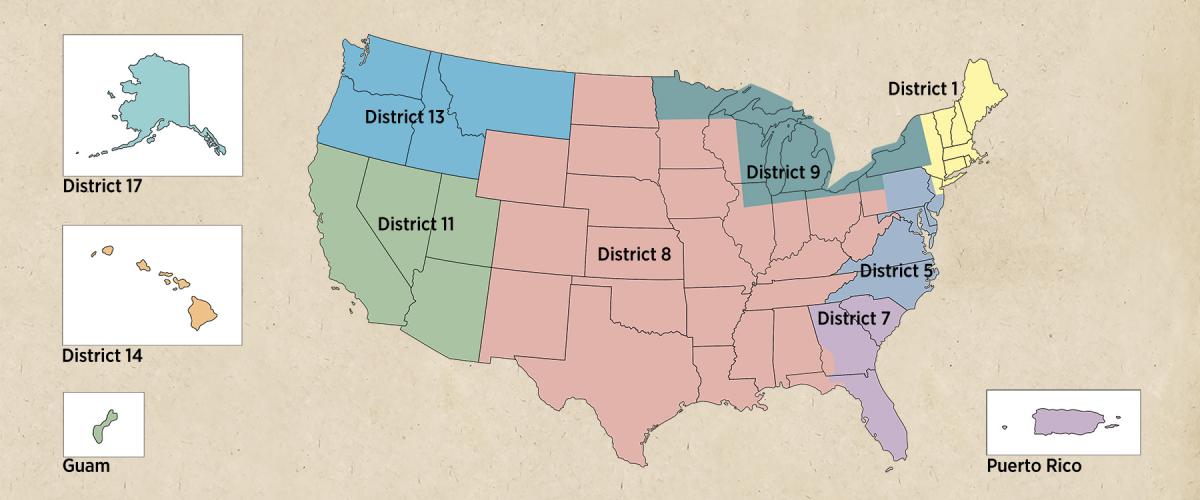

To an outsider, the numbering could look like prioritization, hinting that District 1 is the most important and District 17 the least, which is not true. Also, it begs the question what happened to Districts 2, 3, 4, 6, etc.

This needs to change. Let’s rebrand the districts to emphasize their partnership with and responsibilities to the unique communities they serve. As an example, in 2020, then-Commandant Admiral Karl Schultz renamed Sector Guam as Sector Guam/CG Forces Micronesia to better acknowledge and demonstrate commitment to the whole region (not just one island) it serves.

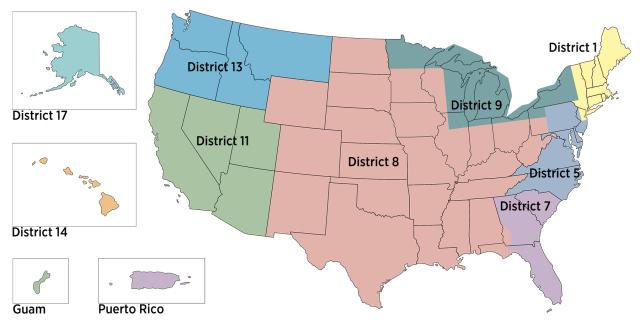

Potential ideas could include:

Coast Guard Forces Atlantic

(Currently Atlantic Area)

• Coast Guard Forces New England (Currently District 1)

• Coast Guard Forces Mid-Atlantic (Currently District 5)

• Coast Guard Forces South and Caribbean (Currently District 7)

• Coast Guard Forces Heartland and Gulf Coast (Currently District 8)

• Coast Guard Forces Great Lakes (Currently District 9)

Coast Guard Forces Indo-Pacific

(Currently Pacific Area)

• Coast Guard Forces California and the Southwest Border (Currently District 11)

• Coast Guard Forces Pacific Northwest (Currently District 13)

• Coast Guard Forces Pacific Islands (Currently District 14)

• Coast Guard Forces Alaska and the Arctic (Currently District 17)

As an additional step, the Coast Guard could time the renaming to align with a new recruiting initiative for both the active-duty and reserve force that offers candidates the opportunity to serve in their home regions or a region in which they would like to live and serve long-term. This could create a sense of purpose, build belonging, and also reduce barriers to accessions.

Acknowledging that certain regions have predicable surge operations—for example, during hurricane season and at the southern border—the Coast Guard could recruit reservists to serve the communities in which they live and work. So, within Coast Guard Forces South and Caribbean and Coast Guard Forces Heartland and Gulf Coast, the service could build reserve “Hurricane Units,” and in Coast Guard Forces South and Caribbean and Coast Guard Forces California and the Southwest Border, it could create reserve “Migrant Units.” These teams would be experts trained and equipped for these responses, serve their careers in their home states, and establish meaningful relationships with their states’ National Guard, FEMA, and other interagency partners that operate in their regional areas of responsibility.

This model would better support the Coast Guard in regionally predicable surge operations while also leaving active-duty operational units intact and reducing the need for surge staffing. To accomplish this, the service might need to consider what post-9/11 missions are less relevant and could be divested. The Marine Corps has done this, on a much grander scale.

There are not many resource-neutral modernization levers we can pull. This is a simple change to better tell the Coast Guard’s story to the nation it serves.

1. National Archives, U.S. Naval Districts and Regional Records, www.archives.gov/research/military/navy/districts.