Russia withdrew its cooperation from the U.N.’s Black Sea Grain Initiative in July ostensibly on the premise that Ukraine might use civilian vessels to transport Western weaponry into the conflict zone, something Russia has been doing so since the early days of the war, as the case of the commercial ship Sparta IV illustrates.

Several months into the Ukrainian counteroffensive and after the Wagner mutiny, Russia withdrew from the Black Sea Grain Initiative following a second successful Ukrainian attack on the Kerch Bridge. Despite the mainstream narrative about the land-centric nature of the conflict, the Black Sea is one of the most strategic areas of the war.

The Black Sea Grain Initiative

On 19 July 2023, Russia announced that “it will consider all ships travelling to Ukraine ports as potential carriers of military cargo.” This decision could be explained as a retaliatory act for the Ukrainian bombing of the Crimean Bridge. Putin’s regime likely suspended the Black Sea Grain Initiative as a means of geopolitical leverage.

Although Ankara is not strictly geographically situated between Ukraine and Russia, it is positioned between their traffic movements at sea. But the sea is always a projection of the land and, with it, all political and geopolitical powers. Turkey continues to see the Black Sea and the Bosporus Strait as a chip to be used when appropriate. In the early days of the war, the Turkish government had not officially closed the Bosporus (even to warships).

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has tried to bring Russia and Ukraine to the table, as both must respect the conditions of freedom of navigation at sea, at least when ships must pass through the Bosporus—a strait that Turkey has closed to warships, thereby curtailing Russia’s capacity to move military vessels from other fleets to the Black Sea. As Ukraine does not have a significant navy, this penalizes Russia more, preventing it from bringing additional naval firepower to the conflict region.

The Black Sea

Russia has tried to take control of the Black Sea since the beginning of the war but has been met with limited success, as demonstrated by the sinking of the Moskva and the Ukrainian recapture of Snake Island. Since then, Russia has changed its approach tactically but not strategically.

Tactically, Russian naval power was limited to mainly strike-support operations or missile launches against land targets—crucially, Turkey’s limitation on warships significantly reduces Russia’s ability to bring more naval firepower to bear. Moreover, the Russian military tried to create a stronghold in Crimea and reinforce the port of Sevastopol, which has been hit by several Ukrainian drone attacks, including the relatively new “Maritime Drones.” These drones went as far as Novorossiysk, a critical hub for Russian military and civil logistics in the Black Sea beyond Sevastopol. Ukrainian tactics resemble guerrilla warfare at sea, but they were enough to force caution in the Russian operations at sea.

However, these tactics have limitations. Russia still has the capacity to shape the destiny of the Black Sea to some degree, with Turkey serving as a major limitation factor at a strategic level. Turkey has already closed the Bosporus to military vessels, but it could do more to restrict some special Russian ships and their cargos that still transit the Black Sea, such as the Sparta IV, Sparta II, Pizhma, and Ursa Major.1 These are all sanctioned ships, which Turkey so far has possibly declined to interdict.

First, the Kremlin’s political narrative is shaped by the need to still appear as a legitimate partner for all the countries interested in having relationships with Russia. For instance, even with the spike of the recent military actions along Ukraine’s coastline and the Ukrainian strike on the Crimean bridge, Russian tour operators did not cancel tourist movements in the region. Russia portrayed itself as a normal country pursuing business as usual and ready to reopen all the economic channels with the West. This is made particularly clear by the sanctioned owner of the Sparta IV, Oboronlogistics [which translates to “military logistics”] LCC. The company’s website tries to convey a sense of normalcy and rarely mentions the war.

Second, the strategic importance of the Black Sea is primarily its logistic value. While Russian military logisticians prefer railroads and have special brigades organized around them, these brigades struggled during the early days of the invasion of Ukraine and can only move a small fraction of the capacity of a ship such as the Sparta IV. Furthermore, “Each battalion can reportedly haul 1,870 tons of cargo (1,190 tons of dry cargo, 680 tons of liquid),” whereas the Sparta IV can bring up to 630 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs, or standard shipping containers) according to the owner.1

Moreover, the geography of south Ukraine’s occupied territories and its railways place Russian logistics under a perpetual risk of attack, as there is only one main access via railway, and it can be attacked at two points (the Crimean bridge being the most important). Intra-line movements are only possible between railways, staging points, and trucks, all readily targetable by Ukrainian systems.

Cargo Ships

Ships are the main way to transport heavy cargo from far places, and Russia is a big country. Moreover, Russia committed itself to several conflicts abroad, including Syria, where it has moved heavy military equipment since 2015—including trucks and tanks. The closest port to the front line is Sevastopol, but the most active and secure one is Novorossiysk, which has military and civilian facilities. When Turkey exercised the Montreux agreement, however, and limited the movement of ships in the Bosporus, Russia was severely restricted from moving military vessels and auxiliaries. Nonetheless, Russia must keep moving goods, and possibly military materials, from the shores of Syria to Russia. The tradecraft developed by a few ships controlled by Oboronlogistics LLC shows how this game is played.

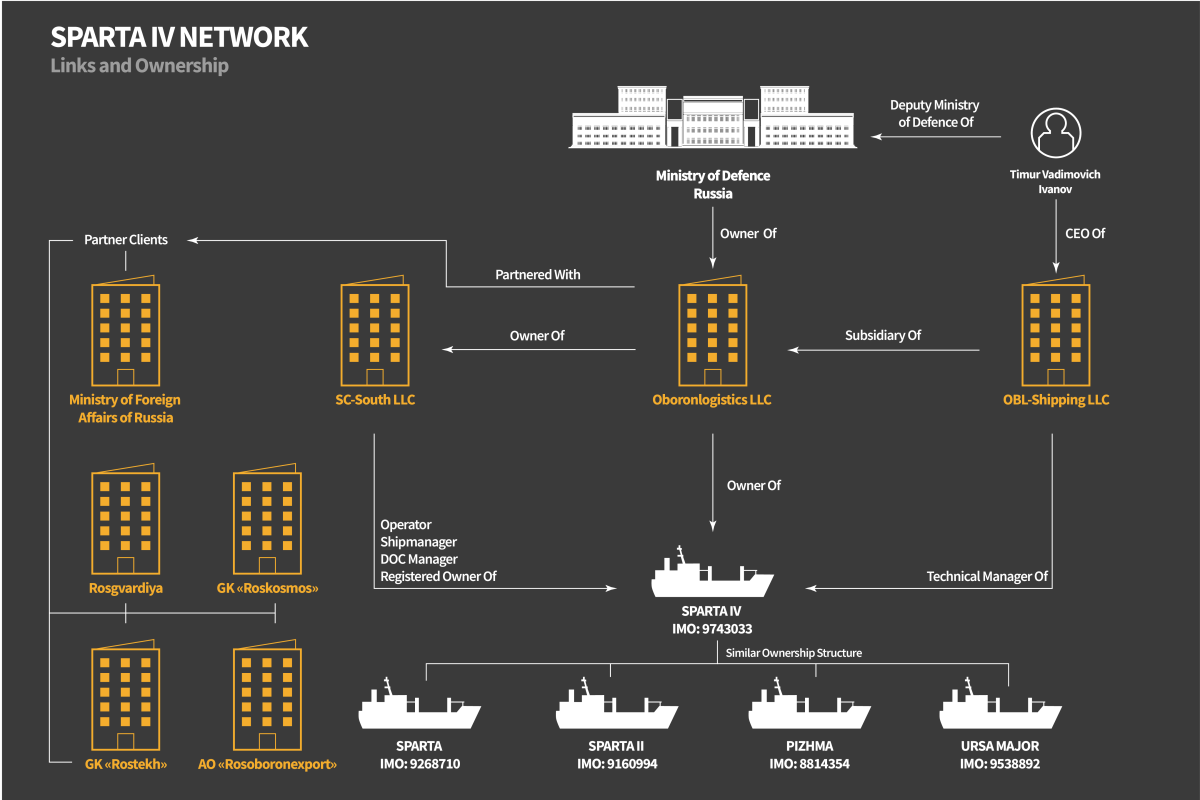

Oboronlogistics LLC has been sanctioned by the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, Australia, and Ukraine for providing logistical support to Russia’s 2014 and 2022 invasions of Ukraine. Furthermore, Oboronlogistics LLC makes no effort to hide its affiliation with the Russian Ministry of Defense; its website explicitly makes this point. The website also mentions the company’s “license to carry out works related to the use of information constituting a state secret,” suggesting the nature of the business carried out by the Sparta IV and the rest of Oboronlogistics LLC’s fleet, which includes the Sparta, Sparta II, Pizhma, and Ursa Major.

OBL-Shipping LLC is an Oboronlogistics subsidiary and is listed as the technical manager of the Sparta IV. The CEO and director of OBL-Shipping LLC is Timur Vadimovich Ivanov, Deputy Minister of Defense of the Russian Federation, and considered “responsible for the procurement of military goods and the construction of military facilities. He ranks tenth in the overall hierarchy of the Russian military leadership.” The EU has sanctioned Ivanov for allegedly profiting from the war in Ukraine.

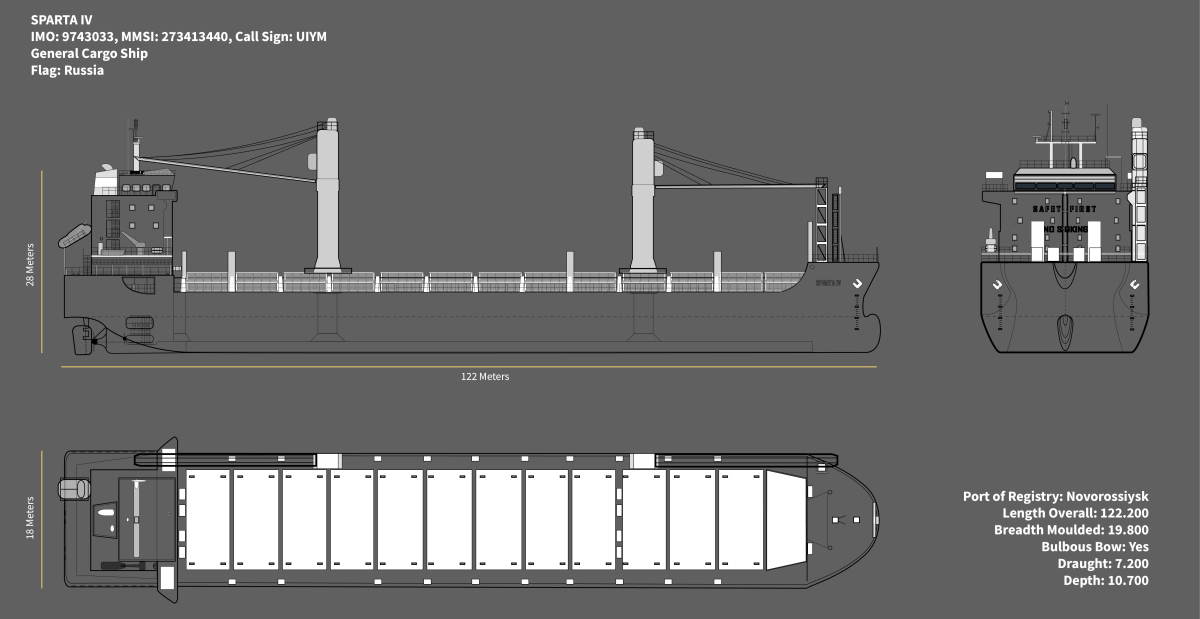

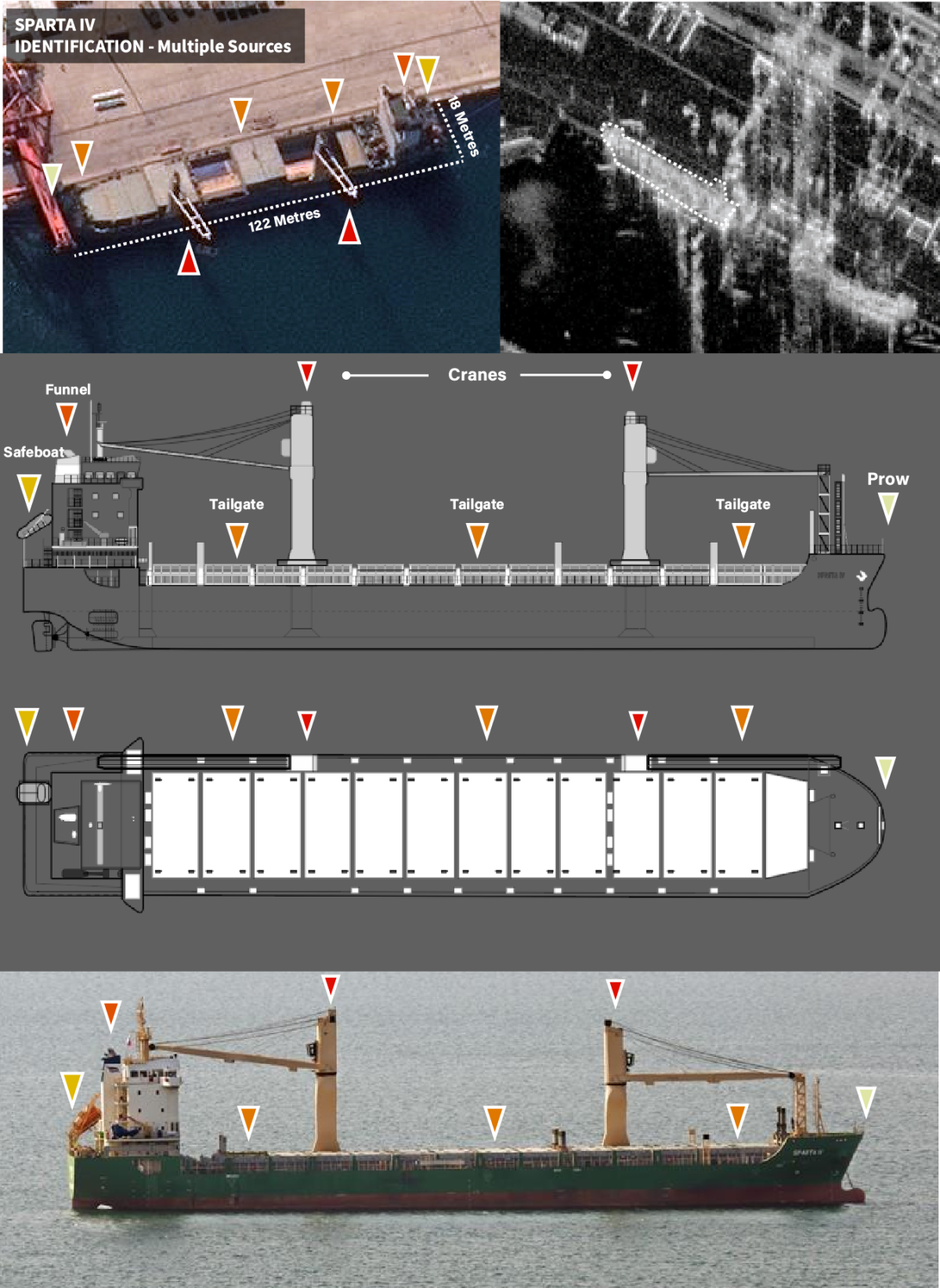

The Sparta IV is a Russian-flagged general cargo ship displacing 8,870 deadweight tons, measuring 122 meters long by 20 meters wideand capable of traveling as fast as 14 knots. The ship’s layout can be seen in multiple commercial and high-resolution satellite images of the ship in the port of Tartus, Syria, in February and July 2023. A recent report published by the Center for Strategic and International Studies convincingly showed that the ship is active and transporting military materiel.

The Sparta IV’s construction and capacity make it an excellent transit vessel for large military materiel, including tanks. The vessel is outfitted with “two cranes with a lifting capacity of 55 tons each,” and it “can transport 630 TEU, including 44 refrigerated containers.” Specifically, these measurements would mean the Sparta IV could transport KAMAZ-5350 tactical trucks.

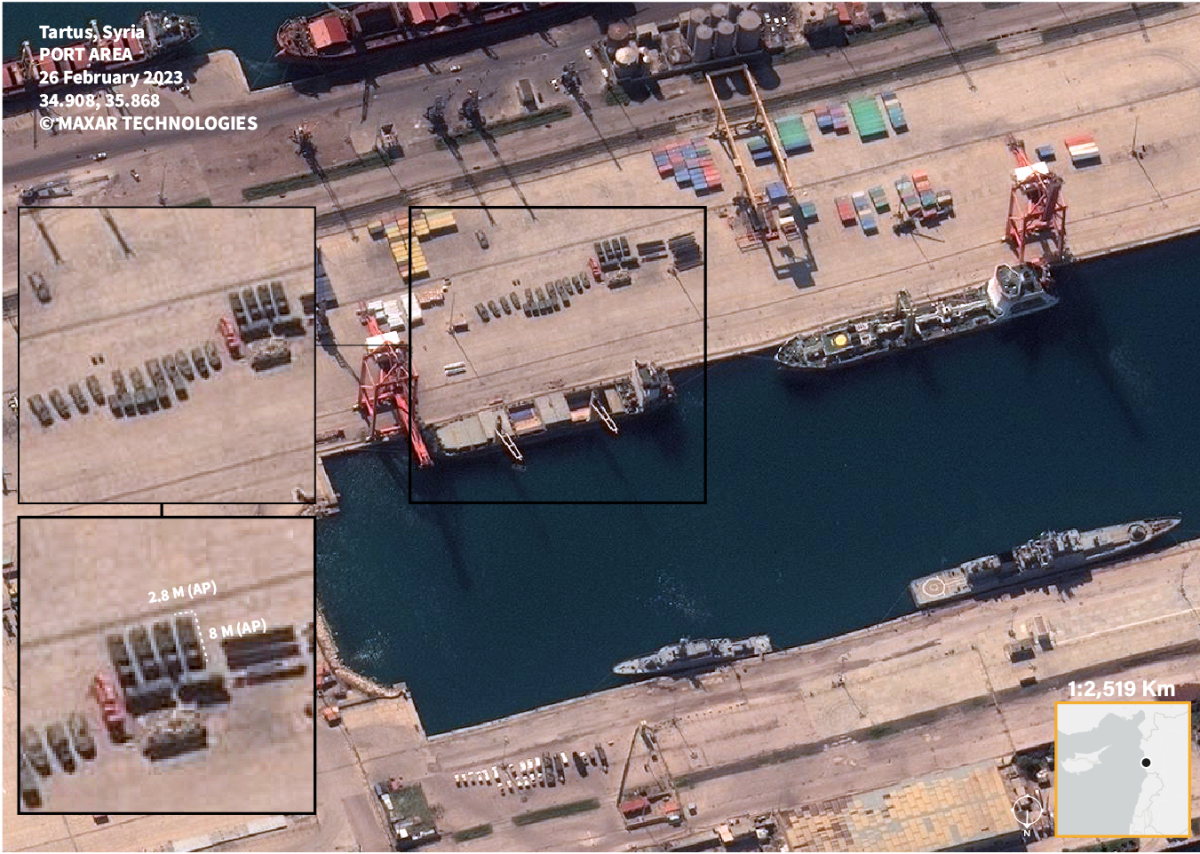

High-resolution satellite imagery over Tartus from 26 February 2023 seems to show 17 vehicles, some of which with measurements (approximately 8 meters long and 2.5 meters wide) compatible with those of a KAMAZ-5350.3

Oboronlogistics LLC is also involved with road transportation and employs the KAMAZ-6560.4 The Sparta IV is reportedly related to another vessel named the Sparta II, which was moving the S-300 air-defense system. This is a precedent for a similar ship with a similar ownership structure.

The Sparta IV’s pattern of life is also telling. The vessel would depart from Novorossiysk military port before approaching Syrian territorial waters, where it would cease Automatic Identification System (AIS) transmissions.5 It would then arrive at Russia’s Tartus naval base, possibly offloading equipment and setting sail again, recommencing AIS transmissions when clear of Syrian waters, before returning to Novorossiysk military port, where its cargo was unloaded.6

The Sparta IV’s AIS transmissions from 1 January to 21 July 2023 revealed that the vessel conducted several transits following this exact pattern between Russia’s naval bases in Novorossiysk and Tartus. High-resolution satellite imagery provided by Planet Labs show the ship in Novorossiysk on 15 July 2023. It seems to show that the Sparta IV brought back other military equipment from Tartus to Novorossiysk.

A Turkish analyst pointed out last year that “Russia is violating the spirit of Montreux by using civilian ships for war.” It is still doing it, and it could be stopped. The Sparta IV’s operations are an example of how Moscow is using what appear to be civilian merchant ships to solve its wartime logistical problems. The international community is aware of Oboronlogistics operations, and several countries have sanctioned the company. It is time now for the authorities find the right way to disrupt and possibly shut down Russia's military logistics operations in the Turkish Straits and the Black Sea.

1. The Sparta IV (IMO: 9743033), Sparta II (IMO: 9160994), Pizhma (IMO: 8814354), and Ursa Major (IMO: 9538892).

2. A TEU (twenty-foot equivalent unit [shipping container]) can carry up to 25,000 kg each, which means that the ship can move approximately 15,750 tons.

3. Satellite imagery provided by Maxar Technologies—RUSI OSIA.

4. The KAMAZ-6560 entered in service in the 2000s and very similar to the KAMAZ-5350, only slightly lengthier: “In February 2017, Oboronlogistics LLC delivered oversized equipment on chassis KAMAZ-6560 in the interests of AO Konstruktorskoe byuro priborostroeniya Akademika Shipunova (design bureau).”

5. AIS data and analysis provided by Geollect.

6. AIS data and analysis provided by Geollect.