China’s strategic culture and historical mine-warfare capabilities have created a PLAN force today that puts significantly more resources into mine warfare than the U.S. Navy does. The modern Chinese Navy was born in the early 1950s to combat the much larger Kuomintang Navy. Led by Xiao Jinguang, a general under Mao Zedong during the Chinese Civil War, the PLAN practiced a policy of “sabotage warfare at sea.”1 A key tenet of this naval doctrine was the covert placement of mines in enemy harbors. In addition, the PLAN integrated Mao’s concept of “people’s war” by using civilian naval assets, such as fishing boats, to assist in PLAN operations.2

Under General Jinguang’s tenure, the PLAN also embraced Mao’s doctrine of “active defense.” This doctrine promotes the implementation of tactically offensive operations to support a strategically defensive strategy; offensively mining Kuomintang ports is a prime example of this policy.3 This tactically offensive yet strategically defensive approach is still visible in the PLAN today and forms the foundation of what Dr. Andrew Erickson, research director in the Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute, calls the PLAN’s “Assassin’s Mace Capability”—a weapon or system that gives an inferior military an advantage against a more advanced one. Offensive mining makes up a fundamental element of the PLAN’s capabilities and has traditionally played a prominent role in PLAN naval doctrine. For example, a mid-2000s Chinese strategic textbook stated, “[We] must make full use of [naval units] … that can force their way into enemy ports and shipping lines to carry out minelaying on a grand scale.”4

In a Taiwan scenario, China could use offensive mining to help blockade Taiwan and delay the interventions of the United States and other nations.5 Another realistic strategy is the offensive mining of key U.S. Navy ports in the Indo-Pacific region, such as those in Japan or Guam. These two scenarios would work in unison. For example, a Chinese National Defense University scholar stated that China could lay mines “in the enemy’s main ports and important channels . . . start[ing] about 10 days before the blockade [would] go into effect.”6

Since the early 2000s, the PLAN has assessed that “relative to other combat mission areas, [the U.S. Navy’s] mine warfare capabilities are extremely weak.”7 The PLAN has capitalized on this advantage by developing more extensive mine inventories and robust delivery methods than the U.S. Navy. China has an estimated 50,000–100,000 maritime mines (only Russia has more, perhaps some 125,000).8 In comparison, the U.S. Navy has fewer than 10,000 naval mines stockpiled, and most are the shallow-water Quickstrike general-purpose bomb-conversion weapons.9 China fields more than 30 different varieties of maritime mines. This diversity provides flexibility in the fuse type, mine type, and case depth required for a wide variety of missions.10

Effective mine delivery systems that can operate in contested areas are vital for the PLAN’s offensive strategy. To understand China’s delivery capabilities, it is useful to examine two hypothetical examples, which could happen near-simultaneously and are only separated analytically for the purposes of evaluating delivery methods.

Conducting a blockade against Taiwan with mines would require mine laying at a scale not seen since the end of World War II.11 Surface warships are still one of the most effective delivery platforms to lay a large quantity of mines. In 2023, the PLAN operates a variety of ships and craft capable of laying minefields in China’s near seas. Moreover, the PLAN can augment its mine-laying capacity with the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia, the China Coast Guard, or requisitioned civilian vessels.12 To rapidly establish a blockade and thereby limit potential interference by Taiwan or the United States, China could supplement surface-laid mines with ones delivered by air. Given China’s near-daily violation of Taiwan’s air-defense identification zone, it is likely China could lay hundreds of mines in one successful wave with little warning.13 These mining operations could also be conducted under the guise of a naval drill, as China regularly conducts mining exercises in the Taiwan Straits and South China Sea and operates surface groups north, east, and south of the island.14

However, once China’s intent becomes clear, the PLAN must have a method to replenish mines in a hostile environment. China’s submarine force is a possible solution to maintain the mine blockade, as submarines are well suited to lay a small number of mines in contested situations.15 Submarines are also ideal for clandestinely laying mines in the approaches to any U.S. Navy forward-operating port within the first and second island chains. Given both the clandestine requirements and need for surprise, submarines offer the only pragmatic method to mining U.S. Navy ports in the Indo-Pacific. Space constraints on submarines, however, are a key drawback to delivering a large number of mines. As a result, the PLAN has developed submarine mine belts—external containers that greatly increase submarines’ capacity to lay mines.16

In addition to PLA Navy ships and submarines, it is important to remember that the China Coast Guard is now the world’s largest fleet of “white hull” ships, and the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia numbers in the thousands. Both non-navy fleets can deploy mines as well.

U.S. Mine Countermeasures: A History of Neglect

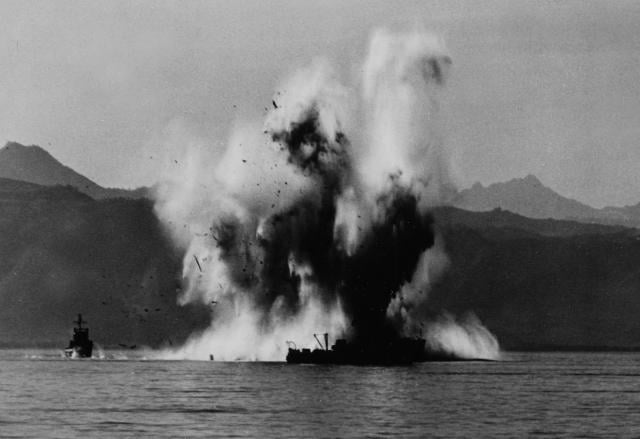

Since 1945, the U.S. Navy has underfunded mine warfare capabilities to its peril. The lessons of World War II minesweeping and the relevant equipment (the Pacific minesweeping fleet of World War II consisted of more than 500 ships) had virtually disappeared by 1950. That same year, the Navy had to relearn the importance of mine countermeasures (MCM) when a 250-ship amphibious task force, flush with victory from the Inchon landing, was forced to sail in circles off the approaches to Wonsan while mines were cleared. As a result, the planned amphibious landing was delayed by more than a week.17 As Admiral Turner Joy, Commander Naval Forces Far East, wrote later: “The main lesson of the Wonsan operation is that no so-called subsidiary branch of the naval service, such as mine warfare, should ever be neglected or relegated to a minor role in the future.”18

The admiral’s advice was ignored, and institutional mine-warfare expertise was lost again over the next 30 years. During the first Gulf War in 1991, the Iraqi navy laid approximately 1,200 mines, successfully thwarting U.S. amphibious assault plans, and sending both the USS Princeton (CG-59) and USS Tripoli (LPH-10) back to the United States for multi-million dollar repairs.19 The Princeton’s repairs alone totaled more than $15 million; the mine that caused the damage cost a mere $1,500.20 Once again, lack of adequate MCM allowed a weaker navy to constrain U.S. options in conflict.

Current Navy MCM capabilities are extremely limited and inadequate to ensure sea control of the approaches to naval bases in the Pacific (let alone break a blockade of Taiwan). Mine Countermeasures Squadron Seven (MCMRON-7) is the primary MCM element in the Indo-Pacific. Forward deployed to Sasebo, Japan, MCMRON-7 consists of Helicopter Mine Countermeasures Squadron 14 (HM-14) Detachment 1 and four Avenger-class (MCM-1) ships (the other four Avenger-class ships are forward deployed to Bahrain). However, all the platforms that make up MCMRON-7 will be decommissioned soon. Notably, HM-14 is scheduled to disband in July of this year.21 The Avenger-class are the only purpose-built surface mine countermeasures ships in the Navy. Yet, they are likely to be decommissioned by 2026 based on recent maintenance contracts for the eight remaining ships.22

Concern over the lack of MCM capabilities is further compounded by numerous assessments, including the “Davidson Window”—the prediction by the former Commander, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, Admiral Phil Davidson, that China could invade Taiwan by 2027.23 The Navy possesses expeditionary mine countermeasure (ExMCM) capabilities, but these assets are not suited for large-scale mine sweeping or hunting. To clear mines on the scale needed to counter the PLAN’s offensive mining capabilities, there is no substitute for dedicated MCM ships.

The Navy plans to replace the aging Avenger-class with the Independence variant littoral combat ships (LCSs) equipped with an MCM module, but these plans are far from solidified. For example, in fall 2022, the USS Sioux City (LCS-11) completed the first LCS MCM deployment to Bahrain.24 In January 2023, Vice Admiral Roy Kitchener, Commander, Naval Surface Forces, said the Navy could send two Independence variant LCSs to Bahrain to use in a similar manner as the four Avenger-class MCMs currently there.25 But in the same statement, he also indicated the Navy was “looking at other options” beyond the LCS to fill the MCM role in Bahrain.26

The Navy needs mine countermeasures capabilities rooted in pragmatism and an understanding of the scale of Chinese mining. Current U.S. MCM shortfalls are somewhat mitigated by the capabilities of allies and partners, notably Japan and South Korea. However, the Navy cannot be overly dependent on allies in such a critical theater because allies and partners’ threat assessments and risk tolerances may diverge from those of the United States. Witness the Philippine government’s gyrations from pro-Chinese to pro-American alignment in recent years. Hoping allies will respond quickly and in a way that supports U.S. operations is not a viable course of action. Without the ability to clear mines out of the approaches to forward-operating ports or around Taiwan in a timely manner, decision makers in Washington will be left with limited options to craft a successful response to Chinese actions in the Indo-Pacific.

Solutions

To remedy the deficit in the Indo-Pacific, the Navy should station more MCM assets in the region and think unconventionally about fielding new MCM vessels. To stage more MCM vessels at ports in the Indo-Pacific, ideally the Navy would build an upgraded version of the Avenger class as some in Proceedings have championed. However, this is unlikely to happen for a variety of reasons—indeed, the Navy’s current 30-year shipbuilding plan does not include such ships. The Navy is planning to replace the four Avenger-class MCM ships in Bahrain. Instead of decommissioning them, the Navy should station them at key naval ports in the Indo-Pacific and continue to maintain them as a stop-gap measure until more concrete solutions are fielded.

The possibility of Iran mining the Strait of Hormuz or parts of the Persian Gulf is a strategic concern, but it pales in comparison to the risk China poses to security in the Indo-Pacific. For this reason, the Navy should not use LCSs to fill the MCM role in Bahrain. Instead, ExMCM detachments could protect the Strait of Hormuz. Also, the nascent détente between Iran and Saudi Arabia slightly diminishes the risk of mine warfare in the Middle East.27 Using ExMCM in the Fifth Fleet area of responsibility would free more LCSs for operations in the Indo-Pacific, where the LCS has shown success conducting maritime counterinsurgency missions in the South China Sea.28 More LCSs in the Pacific in tandem with prepositioning MCM packages in multiple Indo-Pacific ports could allow the Navy to flex additional MCM platforms when needed. The redistribution of Fifth Fleet’s non-ExMCM assets to the Indo-Pacific, in combination with the prepositioning of LCS MCM packages, would allow the Navy to more effectively mitigate PLAN mine-warfare capabilities, while still retaining some MCM capability in the Middle East.

The Navy could also augment MCM capabilities in the Pacific by putting modules on ocean-going tugs. Mine warfare is not limited to traditional gray-hull naval vessels. Using non-naval vessels for MCM has historical precedent. For instance, the Royal Navy in World War II demonstrated the utility of using any oceangoing vessel to conduct MCM.29 In addition, unmanned underwater vehicle improvements offer the ability to operate from any vessel and provide robust MCM capabilities without designing new minesweepers.

If MCM modules are not practical, ExMCM forces, operating out of container express (ConEx) boxes, could be used instead or to further supplement MCM capabilities in the Pacific. More importantly, this idea has already been tested and proven to work on the LCSs. Rear Admiral Brendan McLane, Commander, Naval Surface Force Atlantic, stated at the January 2023 Surface Naval Association symposium, “one of the big advantages of the LCS is it has a big mission bay—you can put a ConEx box in it. And that’s exactly what they did. They put a ConEx box in it with a whole bunch of [MCM] toys and then they played with them.”30 Ocean-going tugs have the space required and are a much cheaper option than the LCS, but the Navy has only a few of them. Without further delay, the Navy needs to reposition MCM assets in the Indo-Pacific and find creative options to build and outfit inexpensive yet capable MCM ships.

Mine warfare has been a part of the naval warfare landscape since the Revolutionary War. After the end of World War II, however, the Navy has often chosen to ignore mine warfare—at its own peril. The PLAN’s offensive mining threat in a Taiwan scenario is anything but hypothetical. In addition to antiship cruise and ballistic missiles, the Navy will have to deal with large numbers of capable Chinese mines. Improving the quality and quantity of MCM capabilities in the Indo-Pacific should be a major priority now. The strategic stakes are high. If the PLAN were able to deny access to critical ports in the theater or the waters around Taiwan by mining, the United States would fail to maintain sea control.

To provide decision makers in Washington with a full spectrum of options in a Taiwan scenario, the Navy must maintain sea control. This is not possible if U.S. warships are moored in port while the Navy repositions MCM assets to clear PLAN mines. Meanwhile, with U.S. forces preoccupied clearing mines from its ports, the PLAN could successfully land a significant invasion force on Taiwan with limited resistance from the U.S. Navy. In such a scenario, the Navy would have to trade critical time to reestablish freedom of movement, while the PLAN could seize strategic terrain and gain the initiative. Only with significant investments today can this costly trade be avoided.

1. Toshi Yoshihara and James R. Holmes, Red Star over the Pacific: China’s Rise and the Challenge to U.S. Maritime Strategy, Revised, 2nd ed., (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2018), 120.

2. Yoshihara and Holmes, 121.

3. Yoshihara and Holmes, 119.

4. Andrew S. Erickson, Lyle J. Goldstein, and William S. Murray, “Chinese Mine Warfare: A PLA Navy ‘Assassin’s Mace’ Capability,” China Maritime Studies, no. 3 (Newport, R.I: China Maritime Studies Institute, U.S. Naval War College, 2009), 2–3.

5. Thomas J. Christensen, “Posing Problems without Catching Up: China’s Rise and Challenges for U.S. Security Policy,” International Security 25, no. 4 (Spring 2001): 29.

6. Erickson, Goldstein, and Murray, “Chinese Mine Warfare,” 29.

7. Erickson, Goldstein, and Murray, 1.

8. “Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2012” (Office of the Secretary of Defense, May 2012), 23; Erickson, Goldstein, and Murray, “Chinese Mine Warfare,” 11.

9. Scott C. Truver, “Not Your Grandfather’s Weapons that Wait,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 147, no. 5 (May 2021).

10. Erickson, Goldstein, and Murray, “Chinese Mine Warfare,” 11–13.

11. Scott Savitz and Scott C. Truver, “Invisible Blockades and Strategic Coercion,” War on the Rocks, 23 November 2022.

12. Andrew Erickson and Conor Kennedy, “Chapter 5: China’s Maritime Militia,” in Becoming a Great “Maritime Power”: A Chinese Dream (Center for Naval Analyses, n.d.), 67; Scott C. Truver, “Taking Mines Seriously: Mine Warfare in China’s Near Seas,” Naval War College Review 65, no. 2 (2012): 10; Erickson, Goldstein, and Murray, Chinese Mine Warfare, 25–27.

13. Ben Lewis, “China’s Recent ADIZ Violations Have Changed the Status Quo in the Taiwan Strait,” Council on Foreign Relations, 10 February 2023.

14. Kris Osborn, “China Is Dropping Bombs and Laying Mines in the Taiwan Strait,” The National Interest, 9 December 2021.

15. Erickson, Goldstein, and Murray, “Chinese Mine Warfare,” 29.

16. Truver, “Taking Mines Seriously: Mine Warfare in China’s Near Seas,” 13; Erickson, Goldstein, and Murray, “Chinese Mine Warfare,” 42.

17. CDR Malcolm W. Cagle and CDR Frank A. Manson, USN, “Wonsan: The Battle of the Mines*,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 83, no. 6 (June 1957).

18. LT Edward J. Rogers, USN, “Mines Wait, But We Can’t!” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 108, no. 8 (August 1982).

19. CAPT David Belt, USN (Ret.), “Damn! . . . The Torpedoes!” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 148, no. 7 (July 2022).

20. Jerry Dickerson, “Princeton Mine Strike…,” A Story Worth Telling, 12 November 2013; Steve Johnson, “Damn the Mines—Full Speed Ahead?” NBC News, 8 January 2003; U.S. Navy Salvage Report Operations Desert Shield/Desert Storm, vol. 1 (Naval Sea Systems Command, 1992).

21. CDR Nicklaus Smith, USN, “World-Famous Vanguard of HM-14 Fly Final Flight,” 9 December 2022.

22. Jan Tegler, “Navy Mine Warfare Teeters Between Present, Future,” National Defense, 17 January 2023; Fincantieri, “U.S. Navy’s ‘Avenger’-class Minesweepers Fleet Maintenance Program to Fincantieri,” 22 March 2022.

23. Mallory Shelbourne, “Davidson: China Could Try to Take Control of Taiwan in ‘Next Six Years,” USNI News, 9 March 2021.

24. Geoff Ziezulewicz, “This LCS Just Completed an ‘Historic’ Deployment,” Navy Times, 5 October 2022.

25. Mallory Shelbourne and Sam LaGrone, “Navy Wants Independence LCS in Bahrain for Mine Countermeasure Mission,” USNI News, 11 January 2023.

26. Shelbourne and LaGrone, “Navy Wants Independence LCS in Bahrain for Mine Countermeasure Mission.”

27. Parisa Hafezi, Nayera Abdallah, and Aziz El Yaakoubi, “Iran and Saudi Arabia Agree to Resume Ties in Talks Brokered by China,” Reuters, 10 March 2023.

28. Megan Eckstein, “Navy Considers Non-LCS Option for Mine Countermeasures in 5th Fleet,” Defense News, 10 January 2023.

29. LT John Miller, USN, “Revitalize Mine Countermeasures,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 145, no. 8 (August 2019).

30. Shelbourne and LaGrone, “Navy Wants Independence LCS in Bahrain for Mine Countermeasure Mission.”