Historical anomalies, by definition, do not last forever. At some point, history rediscovers its baseline. Today’s Navy has seen a nearly eight-decade abnormality, during which no two great powers have clashed at sea—but something closer to normalcy may not be far off.

In East Asia’s littorals, the first island chain is the maritime frontier of the Sino-U.S. strategic rivalry. The littorals flanking China’s coast present the United States its toughest maritime problem: It is where China’s fleet can fight from its feet. No longer can one “define a fleet merely as a set of warships,” wrote the late Captain Wayne Hughes, “because land-based systems play a prominent part.”Thus, the littorals are not just “where the clutter is”; they also are “where the forts are.”1 And the closer China comes to concluding it has the maritime superiority to achieve its political ends by force, the closer the Sino-U.S. rivalry edges toward conflict.

History suggests there is an art to winning an uncertain contest in the littorals. The 1942 Solomon Islands campaign and the 1982 Falkland Islands campaign charted two paths to victory that merged at important crossroads and underscored three important principles of littoral campaigns: The winning side is the one that best integrates the home team, joint sea power, and trusted scouting.2 Having led to victory in both the Solomons and the Falklands, these principles warrant careful study and creative integration by today’s naval force as it readies for its next littoral campaign.

1942: The Solomon Islands Campaign

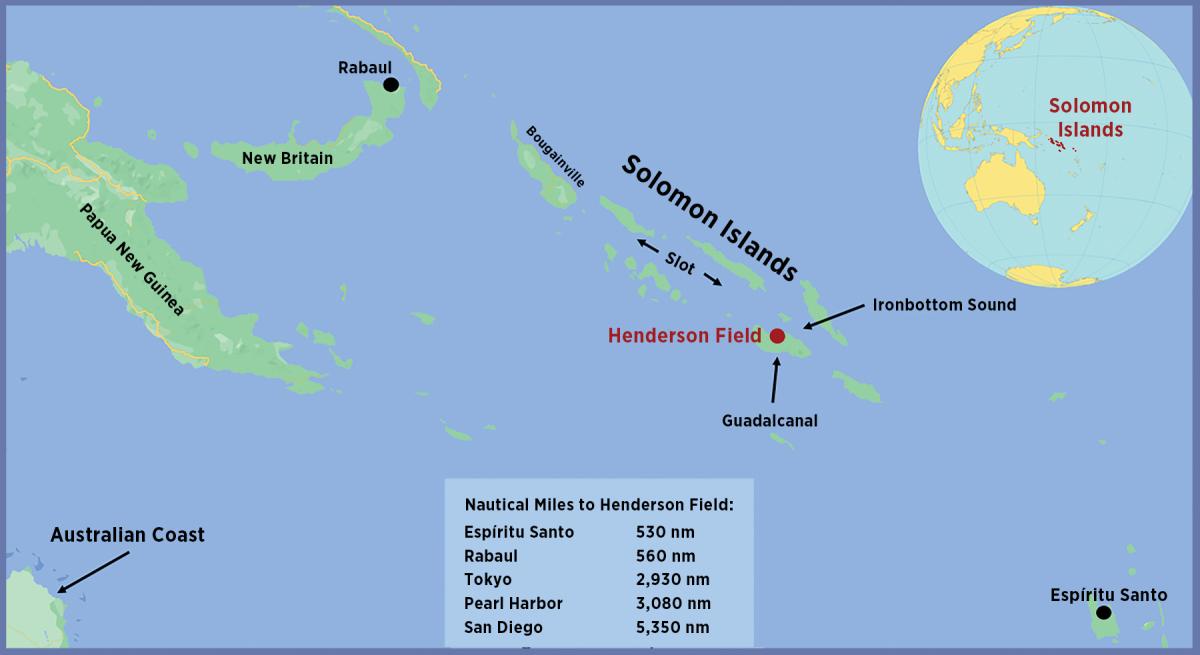

In mid-1942, in a South Pacific island chain equidistant from Imperial Japan and Pearl Harbor, U.S. forces scrambled to open a littoral campaign that would give them the home-team advantage over their peer adversary. With little time to plan, naval expeditionary forces hustled to seize the airfield on Guadalcanal to fulfill two greater objectives: establish maritime superiority to protect vital sea lanes to Australia and advance that superiority by attriting the irreplaceable naval power of an overstretched foe.3

Both U.S. and Japanese forces scrambled into the Solomons, but the Americans did so aided by Australian allies and Melanesian partners.4 With local reporting on enemy disposition, the first U.S. amphibious assault of the war landed on Cactus—Guadalcanal’s codename—“with the smoothness and precision of a well-rehearsed peace-time drill.”5 The Americans seized the airfield, which they named Henderson Field, within 36 hours.

With control of Henderson Field, U.S. air power fought as the home team, weaponizing time and space against the Japanese. Though the Solomons were equidistant from Tokyo and Pearl Harbor, and Guadalcanal was halfway between Rabaul and Espíritu Santo (each side’s nearest operating base), control of the airfield shattered this equilibrium. The Cactus Air Force, an “interservice brotherhood” of American pilots, consistently flew from Henderson Field on interior lines.6 As the home team, most “American pilots who were shot down survived to return to duty,” often helped back by local inhabitants.7

Conversely, Japanese pilots flew 1,200-mile round trips out of Rabaul “at the edge of their fuel envelope” and caged by daylight hours.8 Japanese Zeros could spare, at most, 15 minutes over Guadalcanal.9 Rarely did downed Japanese fliers return to duty, making Guadalcanal a “sinkhole” for irreplaceable pilots—the Imperial Japanese Navy’s center of gravity.10

The home-team advantage also enabled the Americans to integrate joint sea power better than their adversary. Interservice harmony was not preordained in the Solomons. That island chain straddled two Allied theater commands, often slowing time-sensitive reports.11 More acute was Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher’s controversial decision to pull the carriers away on the campaign’s second day.12 Once Henderson Field became operational, though, interservice tensions began to ease.13 Over time, Allied operations in the Solomons became an interdependent trinity of arms: infantrymen protected the Cactus Air Force, the pilots protected naval shipping, and the ships sustained and reinforced all who were ashore. The Americans had found a winning rhythm for the littorals, one that blended the power of the U.S. fleet over land and sea to yield maritime superiority—at least, when the sun was up.

Lacking joint sea power at night, the Americans proved vulnerable to naval night fighting and routinely ceded maritime superiority to Japanese surface forces in the deadly waters known as “Ironbottom Sound.” Like strange clockwork, there was “a change of sea command every twelve hours.”14 In daylight, U.S. air power reached out, letting U.S. sea power reach in. But with aviation grounded nightly, Japanese warships returned to bombard Henderson Field and rush reinforcements ashore in what Americans dubbed the “Tokyo Express.” Only round-the-clock bursts of local sea control by Allied surface forces could sever Japan’s operational sustainment.15 To do that, the Allies would have to out-scout their enemy.

The cramped littorals of the Solomons proved that the surest way to strike effectively first was to scout effectively first. The campaign began with displays of both the strengths and weaknesses of Allied scouting. Two hours after U.S. Marines began phasing ashore, 54 planes of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s 11th Air Fleet sortied from Rabaul to attack U.S. transports.16 A deep-scouting network of 64 Australian coast-watching stations, observing the enemy’s main approach known as the “Slot,” gave the Americans sufficient warning to defend against the attacks, at high cost to the Japanese.17 The following day, the Japanese tried a similar air raid and earned similar results, setting a trend in which Japan’s renowned aviators could not punch through an alert Allied naval defense.

On the campaign’s second night, though, fumbled scouting led to U.S. defeat at the Battle of Savo Island. As Japanese Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa’s surface strike force steamed from Rabaul, Allied forces detected it five times.18 But untrustworthy and delayed reporting misled Allied commanders in Ironbottom Sound.19 Moreover, with radar recently installed on only a few U.S. warships and understood by fewer commanders, the Americans were caught in a crucial technology transition.20 In short, the first of many confused night battles revealed that “Japanese eyes excelled American radar.”21 Admiral Mikawa’s force scouted effectively first, quietly sending Type 93 “Long Lance” torpedoes into Ironbottom Sound to strike effectively first.

Maritime superiority at night—that last obstacle to victory in the lower Solomons—demanded networked scouting. Ultimately, Allied success in this uncertain littoral contest came from integrating the home team, joint sea power, and trusted scouting—three elements that reappeared 40 years later in the South Atlantic.

1982: The Falkland Islands Campaign

In April 1982, much like the Solomons, the campaign for the Falklands opened suddenly, with Argentina and Britain each scrambling forces. Though maps show just how un-equidistant the Falklands are—275 nautical miles from Argentina and 6,700 from Britain—the British still managed to chart a path to victory that found them holding the home-team advantage.

This odd reality, wherein Argentina’s forces fought the away game, is explained at the strategic level by the Falklanders’ embrace of self-determination.22 Because Falklanders wanted to remain British, Britain had the advantage of fighting on the right side of an international norm. And right, it turns out, can also make might. For instance, the United States ceased being neutral and “firmly declared itself in favour of the British cause,” and with its support, the British turned remote Ascension Island into a vital “forward fleet and air base in a matter of days.”23 The United States then supplied Britain with critical air-to-air Sidewinder AIM-9L missiles, while France stopped selling equally critical air-launched Exocet sea-skimming missiles, limiting Argentina to the five it held when the war began.24 With Argentina isolated from meaningful third-party support, the British task force launched into an uncertain littoral campaign, one that had to gain maritime superiority to retake the Falklands.

At the operational level, Britain used integrated sea power to exploit Argentina’s disjointed armed forces. Britain’s Royal Air Force struck first on 1 May with Operation Black Buck, in which 18 Victor air-to-air refueling sorties fed a Vulcan bomber over its 7,800-mile round-trip flight from Ascension to bomb the runway at Stanley, the Falklands’ capital.25 Though some questioned this raid’s significance, the official British history concludes, “It ensured [Argentine] Skyhawks and Super Etendards could not use the airfield.”26 Argentina also recalled its Mirage III fighters, reprioritizing homeland defense, as Ascension-based bombers also could range northern Argentina.27 Through deft operational fires, Britain kept Argentina’s Air Force from basing out of the Falklands, slashing enemy time-on-station to two or three minutes.28 The Argentines would have no Henderson Field.

The next day, Britain’s joint sea power struck from under the sea, again using tactical actions for operational effect. HMS Conqueror, having tracked the Argentine cruiser General Belgrano for 500 nautical miles, was about to lose her prey to shallow waters.29 With this trusted scouting window about to close, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher authorized the sinking of the General Belgrano.30 The Argentine Navy, jarred by the subsurface violence, forfeited all sea lines of communication with the Falklands, “effectively taking itself out of the war.”31

The littorals certainly vexed Britain’s joint sea power, as commanders quarreled over carriers and murky command relationships in ways that echoed the Solomons.32 But the effects of Black Buck and the sinking of the General Belgrano made things worse for Argentina’s jointness. The “conditions were set for a professional joint force to close with a conscripted, disjointed adversary.”33 The British knew Argentina’s bid for success rested with its pilots flying from afar to try to create an Ironbottom Sound in South Atlantic waters.

Antiscouting actions to frustrate enemy scouting were Britain’s best chance to prevent Argentine pilots from sinking a carrier or massive troop transport. Without trusted scouting, Argentine pilots flew great distances to launch precious few Exocets at whatever first radar contact registered from “roughly the right bit of ocean.”34 One reason Argentine pilots failed to scout better was that British Sea Harriers dominated local skies, leading Argentina’s Air Force to withhold from battle until the British committed to landing operations.35 With Argentina preserving its air power as a form of sea denial in-being, and with the South Atlantic winter closing in, the British devised a bold plan that weaponized time and space to transition its center of gravity ashore.

Everything hinged on Britain’s task force applying each principle to make the littorals more dangerous for the enemy. Named after the commodore for amphibious warfare, Michael Clapp, the task force maneuvered into Falkland Sound before sunrise on 21 May to construct the “Clapptrap,” a multidomain defense in depth.36 British submarines held Argentina’s Navy at bay while scouting for air-attack sorties from mainland bases; missile-equipped surface pickets screened approaches inside Falkland Sound; Harriers patrolled local skies; and Rapier ground-based air defenses were helicoptered onto hilltops. Argentine pilots renamed the Clapptrap “Death Valley.”37 Some British picket ships still paid dearly, but the British were now a fleet on land and sea.38 By turning home-team advantages into joint sea power that could out-scout and defeat an isolated adversary—principles witnessed in the Solomons—the British won an otherwise uncertain littoral contest in the Falklands.

Today: The First Island Chain Campaign

The first island chain campaign has already begun, with Sino-U.S. strategies competing for maritime superiority. Should this competition erupt into conflict, U.S. naval forces must be enough at home in those distant littorals to win. And as the Solomons and Falklands illustrated, the home-team advantage goes to whomever shares the closest purpose with the local population, not necessarily the closest geography.

Today’s map puts the first island chain under the shadow of China’s maturing precision-strike regime and burgeoning fortress fleet. Viewed from another angle, though, this chain offers a geostrategic maritime perimeter that flanks China’s coastline from end to end. As one measure of home-team advantage, “U.S. allies or partners occupy the entire island chain,” with some 54,000 American service members living there.39 If China cannot, through competition, alter the fact that its Pacific access is contingent on U.S. allies and partners, it may try to alter that fact by force.40 It is the away team’s plight to have to show up to change the facts on the ground; home teams muster to defend those facts.

As in the Solomons and the Falklands, a conflict over the first island chain will see U.S. forces gain maritime superiority only if they can turn home-team advantages into resilient joint sea power—blending ships and forts to become more than the sum of the parts. The old adage, A ship’s a fool to fight a fort, ought to go a step further in today’s littorals: It’s also a fool to fight without forts. Thus, the People’s Liberation Army cannot have a monopoly on fielding a fleet that can fight from its feet.

Like Henderson Field, smaller forts on or near principal objectives will punch above their weight. They will be localized positions of advantage—static or mobile, persistent or temporary—that advance maritime superiority through any domain. By leveraging key maritime terrain through operational art, these well-positioned forts can make allies out of time and space.

Joint sea power will require an array of allied forts as an economy of force that denies local waters, freeing allied ships to concentrate effects at decisive points through local sea control. Maritime superiority will not come all at once, but through innumerable on-again, off-again sea-denial and sea-control actions set within a broader design. Littoral campaign and operational designs must lay out heavily scouted corridors that feed decisive points, just as the Slot fed Ironbottom Sound and Falkland Sound fed Death Valley. Put simply, allied joint sea power must make the littorals more dangerous for the away team.

Over the past 80 years, the value of trusted scouting has only increased. As a basic rule, when the range of a missile doubles, the scouting area to employ it quadruples.41 Along with covering all that space, scouting also covers “five of the six steps in the kill chain [that] center on sensing.”42 War’s evolving character thus pits a firepower surplus—a family of far-reaching missiles—against a scouting shortage. Tactical actions to reduce enemy scouting can yield operational results by fading threat rings long enough to mass effects. This will spark intense scouting-antiscouting contests that leave each side’s operational picture somewhere between blurred and blind. Echoing the day-night struggle around Guadalcanal, maritime superiority around the first island chain will ebb and flow with the back-and-forth exchange of scouting dominance.

Allied joint sea power, operating from the home field, must bring together a scouting mosaic while guarding against the two pitfalls in the catchphrase “any sensor, any shooter.” First, trust in the sensor matters. Overly inclusive, unvetted scouting exposes decision-makers to being misled by error or deceit. Trusted scouting must acknowledge confidence in the source as well as the source’s confidence in its report. Second, economy of the shooter matters. All targeting windows will have an expiration, driving the need for anticipatory permissions and authorities. And because the adversary can make mass a strength, shooter-to-target pairing will require operational-level efficiencies. Falling short of these nuances, “in the next war at sea we will see ships with empty missile magazines and little to show for the expenditure of what should have been the decisive weapon.”43 A trusted-scouting network, integrated across the force, must be at the center of campaign design and execution.

Lessons to Relearn

History is eager to reteach lessons unlearned. With “more than seventy years [having] passed since the U.S. Navy fought a fleet action,” there is temptation for the novelties of the present to crowd out the lessons of a distant past.44 But these principles of littoral campaigns are just as relevant today, 40 years after 1982, as they were 40 years before. By integrating the home team, joint sea power, and trusted scouting, today’s naval force can gain and maintain maritime superiority to achieve a greater end.

A century ago, Sir Julian Corbett professed to his seagoing countrymen, “Command of the sea is only a means to an end.”45 He based this claim on a simple truth: “Men live upon the land and not upon the sea.”46 Today’s naval force must think of maritime superiority in East Asia’s littorals as the means by which facts on land will be either altered or upheld. This Corbettian logic compels integrated thinking: America needs allies, fleets need feet, shooters need scouts. Such basic principles can give the United States the upper hand in the first island chain. And perhaps, by doing that, allied maritime superiority in those distant littorals can work against history to prolong a most worthwhile anomaly.

1. CAPT Wayne P. Hughes Jr. and RADM Robert P. Girrier, USN (Ret.), Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, 3rd ed. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2018), 161.

2. The first two principles, the “home team” and “joint sea power,” were inspired by and adapted from James Holmes, William Bowers, and Thomas Wood, “The Seventh Cornerstone of Naval Operations: The Home Team Has the Advantage,” Marine Corps Gazette, December 2021. Similar inspiration and adaptation for “trusted scouting” is most attributable to Hughes and Girrier, Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations.

3. Bradford Lee, “A Pivotal Campaign in a Peripheral Theatre: Guadalcanal and World War II in the Pacific,” in Naval Power and Expeditionary Warfare (London and New York: Routledge, 2011), 89.

4. Richard Frank, Guadalcanal (New York: Penguin Books, 1992), 28; Lee, “Pivotal Campaign,” 94; Samuel Eliot Morison, The Struggle for Guadalcanal: August 1942–February 1943, vol. 5, History of the United States Naval Operations in World War II (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1984), 11.

5. Frank, Guadalcanal, 61.

6. James D. Hornfischer, Neptune’s Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal (New York: Bantam Books, 2011), 124.

7. Frank, Guadalcanal, 208.

8. Hornfischer, Neptune’s Inferno, 124.

9. Lee, “Pivotal Campaign,” 94.

10. Frank, Guadalcanal, 209 and 214.

11. Craig L. Symonds, “Guadalcanal: Jungle Warfare,” lecture 8 in “World War II: The Pacific Theater,” The Great Courses; Frank, Guadalcanal, x.

12. Frank, Guadalcanal, 54; Hornfischer, Neptune’s Inferno, 33–36; Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, 27.

13. Marine Corps University, “How to Fight and Win the Single Naval Battle: Operation Watchtower’s Relevance Today,” a case study published, in part, in Marine Corps Gazette, April 2018, 18.

14. Frank, Guadalcanal, 210.

15. Trent Hone, “Guadalcanal Quintet,” Naval History, October 2021. Hone asserts that “resupply and reinforcement were the deciding factors in the struggle for the island.”

16. Hornfischer, Neptune’s Inferno, 46.

17. Frank, Guadalcanal, 28 and 69.

18. Frank, Guadalcanal, 89–96.

19. Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, 19–27.

20. Hornfischer, Neptune’s Inferno, 104; Harlan K. Ullman, “Is Cyber Where Radar Was in 1942?” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 145, no. 6 (2019).

21. Frank, Guadalcanal, 163.

22. Lawrence Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, vol. 1 (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2005), 18. Graham Bound, Falkland Islanders at War (South Yorkshire, UK: Pen & Sword, 2002).

23. Martin Middlebrook, The Argentine Fight for the Falklands (South Yorkshire, UK: Pen & Sword, 2003), 74; and Sandy Woodward, One Hundred Days (Annapolis, MD: Bluejacket Books, 1997), 86.

24. Peter Hore, “Logistics Miracle,” Naval History, April 2022, 25; Max Hastings and Simon Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1984), 142 and 207; Steven Iacono, “A Failure in the Falklands,” Naval History, April 2022, 16; Theodore L. Gatchel, At the Water’s Edge: Defending Against the Modern Amphibious Assault (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1996), 189.

25. Kenneth Privratsky, Logistics in the Falklands War (South Yorkshire, UK: Pen & Sword, 2016), 85.

26. Lawrence Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, vol. 2 (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2005), 284–85; Middlebrook, Argentine Fight for the Falklands, 78; “First Strike of the Falklands War,” documentary, October 2014, 44:55, www.youtube.com/watch?v=X2Yl8ntVS-4.

27. Freedman, Official History of the Falklands Campaign, vol. 2, 286.

28. Gatchel, At the Water’s Edge, 192.

29. Middlebrook, Argentine Fight for the Falklands, 105.

30. Freedman, Official History of the Falklands Campaign, vol. 2, 292; Hastings and Jenkins, Battle for the Falklands, 148–49.

31. Hughes and Girrier, Fleet Tactics, 149; Gatchel, At the Water’s Edge, 195.

32. Each of the top commanders wrote about the British command arrangements and aircraft carrier employment. See: Woodward, One Hundred Days; Michael Clapp and Ewen Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands: The Battle of San Carlos Waters (Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Books Limited, 2012); Julian Thompson, 3 Commando Brigade in the Falklands: No Picnic (Yorkshire, UK: Pen & Sword, 1985); and Freedman, Official History of the Falklands Campaign, vol. 2, xxx–xxxii.

33. Capt Dustin Nicholson, USMC, “Argentina’s Gray Zone Gambit,” Naval History, August 2019, 49.

34. Woodward, One Hundred Days, 12; Freedman, Official History of the Falklands Campaign, vol. 2, 303–4 and 490; Gatchel, At the Water’s Edge, 195.

35. Freedman, Official History of the Falklands Campaign, vol. 2, 445.

36. Clapp and Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands, 116; and Freedman, Official History of the Falklands Campaign, vol. 2, 448.

37. Middlebrook, Argentine Fight for the Falklands, 168; and Hughes and Girrier, Fleet Tactics, 150.

38. It is worth noting just how much fortune favored the bold here. Several bombs that hit British warships failed to detonate because of fuzing that had not accounted for Argentina’s pilots having to hug the sea inside Death Valley.

39. Holmes, Bowers, and Wood, “Seventh Cornerstone of Naval Operations,” 11.

40. Nozomu Yoshitomi, “How Japan Can Help Save Taiwan: Securing the First Island Chain,” War on the Rocks, 23 March 2022.

41. Hughes and Girrier, Fleet Tactics, 185–91.

42. The six steps of the kill chain are: find, fix, track, target, engage, and assess. Quote from Gen David Berger, USMC, “#DPC22—Gen. David H. Berger,” Defense Programs Conference, filmed 14 March 2022, youtube/WB2map2hLC4. See also, Christian Brose, The Kill Chain: Defending America in the Future of High-Tech Warfare (New York: Hachette Books, 2020), xviii–xxii.

43. Hughes and Girrier, Fleet Tactics, 195.

44. Hughes and Girrier, Fleet Tactics, xxxi.

45. Julian Corbett, England in the Seven Years’ War: A Study in Combined Strategy, vol. 1, 2d ed. (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1918), 6.

46. Julian Corbett, Some Principles of Maritime Strategy (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1988), 16.