It has been slightly more than a year since, on 17 December 2020, the Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard released the latest in a long line of maritime strategies, visions, white papers, guidance, and operational concepts, harkening to at least Samuel Huntington’s iconic Proceedings article in 1954.1 Following a three-year gestation, the triservice maritime strategy, Advantage at Sea: Prevailing with Integrated All-Domain Naval Power, promises strategic guidance on how the Sea Services will prevail in day-to-day competition, crisis, and conflict during the next decade.

Advantage at Sea focuses principally on China and Russia, although Iran, North Korea, and other potential adversaries also are concerns.2 The value of Advantage at Sea depends on strategy, planning, and program stability and consensus among naval warfare communities. If the past 14 months mean anything, however, stability and consensus look to be in short supply. Indeed, as Representative Elaine Luria (D-VA) warned, “The Navy does not have, and has not had, a maritime strategy for the past 30 years. Moreover, the past 30 years have seen failures in ship class after ship class, resulting in a lost generation of shipbuilding.”3

The 2021 Strategic Discussion about the Future Fleet

The past year saw no shortage of debate and commentary on the triservice maritime strategy and the future of the fleet. This section captures some of that to provide context for the rest of the column.

“One of the key tenets [of Advantage at Sea] is the return to the thought process of control of the seas,” Rear Admiral James Bynum, acting Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Warfighting Requirements and Capabilities, underscored in December 2020.4 “We were just coming out of the Vietnam era where we had free, unfettered access to support operations in land-based warfare. We’re coming off a similar though much more prolonged set of time in the Middle East. As we look away from that and acknowledge there are global comprehensive actors out there where we no longer enjoy assured access in the sea, and assured access to the sea today because of those places where we need to go to confront those malign actors.”

Several months later, at the Oxford Talks, Bynum confirmed the new Biden administration’s focus.5 “China is the United States’ most pressing threat. It also represents a comprehensive threat to our allies and partners, and all nations that support a free and open system.”

“President Joe Biden might understandably treat the . . . triservice maritime strategy in a similar fashion to Trump’s proposed 2022 budget: with skepticism,” researchers Jonathan Caverley and Sara McClaughlin Mitchell mused.6 “America’s Sea Services have been at the forefront of the Trump administration’s last-minute national security maneuvers with the December releases of both a new 30-year shipbuilding plan [Battle Force 2045] and the new maritime strategy. Trump loved talking about building ships (although he did little to advance this goal) . . . despite this, the new administration should take the new strategy document seriously.”

With caution, however. “Don’t knock yourself out,” analyst Paul van Hooft warned in February 2021.7 “The United States should give up its quest for command of the maritime commons in the western Pacific. The struggle is based on a false premise—that if the United States loses command of the seas, China will step in to fill the vacuum. In fact, even if the United States loses command of the maritime commons, China is not positioned to gain it. However, by positioning China as an existential threat, the United States is boxing itself in politically. The United States courts disaster when it overextends itself by seeking military primacy in the region.”

Van Hooft explained, “In contrast to their U.S. counterparts, Chinese planners are essentially only solving one military problem against one adversary. As the United States looks to decisively defeat China, China simply focuses on raising the costs of U.S. power projection. By doing so, it can create fissures between the United States and its allies. China does not need to win a possible shooting war, but it must deny the United States a clear victory in one.”

And, as Evan Montgomery noted, “During the administration of Donald Trump, senior officials made it clear that although competing with China and Russia was their top priority, countering North Korea and containing Iran were not far behind.Indeed, over the past four years, maximum pressure campaigns against minor powers consumed the attention of U.S. policymakers and drew military resources away from more serious threats. Even if President Biden’s administration is more restrained when it comes to the Pyongyangs and Tehrans of the world, it is still inheriting the same set of rivals and will still struggle to manage them all.”8

Caverley and Mitchell suggest that “the same forces posited by the strategy (and its associated shipbuilding plan) for a Sino-American slugfest can also serve a less directly confrontational approach to great-power competition, and indeed, the strategy clearly lays out a liberal logic for seapower. Barring catastrophic war, competition with China will likely take place around the world over goods and issues held in common across many states. Managing conflict in this system, providing public goods, and protecting sea lanes is facilitated by building a larger U.S. Navy.”9

“Perhaps it is impolitic, or insufficiently optimistic in a strategy document, to mention that the inflection point has already passed, and we are in rapid decline,” Michael Sinclair, Roderick H. McHaty, and Blake Herzinger at Brookings cautioned.10 “The U.S. Navy’s seagoing fleet is too small to do the things being asked of it and may still get worse. Maintenance is suffering and peacetime deployment rates are unsustainable. Programs intended to replace decommissioning ships are foundering, from the troubled littoral combat ship to the three-ship white-elephant Zumwalt class. The first ship in the new Constellation class is not due to be delivered until FY 2026. In the background, the Navy’s 30-year shipbuilding plan calls for decommissioning 11 Ticonderoga-class cruisers by FY 2026, along with 37 other ships scheduled to leave service between FY2022 and FY2026. Today’s fleet is at ebb tide. An aggressive building plan released in December 2020 showed the Navy’s path to reaching a 355-ship battle force sometime between 2031 and 2033.”

On 29 November 2021, the Defense Department released the 2021 Global Posture Review (GPR).11 The review came at a key inflection point following the imminent end of operations in Afghanistan and ongoing development of the new National Defense Strategy (NDS). The 2020 Interim National Security Strategic Guidance shaped the GPR’s assessment of the Department of Defense’s (DoD’s) posture across major regions outside the United States and developed near-term posture adjustments, posture planning guidance, and analysis on long-term strategic issues. “Through these assessments, the GPR will help strengthen posture decision- making processes, improve DoD’s global response capability, and inform the drafting of the next National Security and National Defense Strategies that will provide frameworks for the future fleet.”

Meanwhile, the Navy and Pentagon were performing separate studies on the future fleet architecture.12 The Pentagon’s Office of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE) is assessing the fleet design for the FY2023 budget that will come out in calendar year 2022, while the Navy is analyzing the fleet architecture needed to counter future threats past the FY2024 budget.

“I think that the global posture will help give us a better understanding of where we stand right now to answer the secretary’s questions about implementation of the NDS and whether any changes are required,” Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Michael M. Gilday recognized.13

A Range of Force Levels

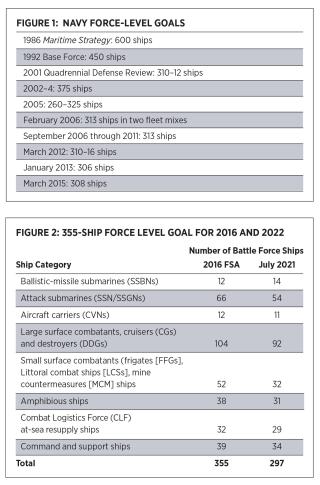

In 2016, the Navy conducted a force structure assessment (FSA) that recommended a 355-ship goal of certain types and numbers, according to Congressional Research Service (CRS) analyst Ronald O’Rourke.14 “In an FSA, the Navy receives inputs from U.S. regional combatant commanders (CoComs) regarding the types and amounts of navy capabilities they deem necessary for implementing the Navy’s portion of the national military strategy. . . .The [Navy] then translates [CoCom] inputs into required numbers and types of ships, using the current forces as a baseline.” Previous Navy force-level goals are shown in Figure 1.

These FSAs are not the Navy’s annual congressionally mandated 30-year shipbuilding reports. The December 2020 “Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels” reflects the result of a future naval force study (FNFS) that assessed competitive advantage in great power competition through 2045. The new goal is expected to introduce a more distributed fleet architecture featuring a smaller proportion of larger ships, a larger proportion of smaller ships, and a new third tier of large, unmanned vessels (UVs).

During 2020, the Navy, in conjunction with Pentagon civilian leaders, cost and analysis experts, a dedicated red team, and outside naval analysts developed a “foundational” future naval force structure assessment (FNFSA) that called for a dramatically larger fleet. This Battle Force 2045 plan was released in the waning days of the Trump administration.

Because the analysis was comprehensive and new, in January 2022 Admiral Gilday still viewed that plan as viable: “I think the Navy is in a really strong position right now to continue to argue for a bigger, better Navy based on, grounded on, the Future Naval Force Structure Assessment. . . . I think that [review] has very clearly allowed us to see what the composition of the future fleet has to look like in order to not only compete but to beat the Chinese.”15

The Navy’s December 2016 force-level goal—in early 2022 still the FSA of record—outlined reaching and maintaining by 2045 a fleet of 355 battle-force ships. On 15 July 2021, the in-service fleet numbered 297 ships, as shown in Figure 2.

Battle Force 2045 envisioned a distributed fleet architecture of 382 to 446 manned ships and 143 to 242 large unmanned or optionally manned vessels. Yet in June 2021, the Navy submitted to Congress an update to its 2020 long-range shipbuilding plan, stepping back from the 355-ship fleet and instead articulating priorities for a future distributed naval force.16 The new plan laid out a fleet as low as 321 and as large as 372 manned ships. The high-end fleet would counter threats from China and Russia in a future fight. The lower number reflects mid-2021 reality-based fiscal constraints and industry capacity.

The Heritage Foundation’s annual Index of Military Strength called for a 400-ship fleet, noting that the current 297-ship Navy is “inadequate and places greater strain on the ability of ships and crews to meet existing operational requirements.” The Index calls for a force composed of 13 carrier strike groups; 13 airwings (totaling 624 strike aircraft); and 15 expeditionary strike groups.17 The Index also notes that unmanned vessels are still in their infancy and their potential contribution to naval power is unknown.

Those 321 to 372 manned ships would be supplemented by a yet-to-be-determined force of between 77 and 140 unmanned surface and underwater vessels. The Navy’s 2021 update promised a detailed long-range plan with the submission of the FY2023 budget request in 2022. That effort only began in September, Admiral Gilday told a Defense One event, noting it will be informed by ongoing fleet experiments and exercises focused on new operating concepts such as distributed maritime operations, expeditionary advanced base operations, and littoral operations in a contested environment.18

“If the Navy adhered to the schedule for purchases and ship retirements outlined in its Battle Force 2045 plan,” the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO’s) Eric Labs explained, “the inventory of manned ships would rise from about 300 to about 400 by 2038. The force of unmanned systems would rise from just a few prototypes today to about 140 by 2045.”

However, that force will not come cheap. “The December 2020 plan would require average annual shipbuilding appropriations almost 50 percent larger than the average over the past five years,” Labs predicted. “CBO estimates that total shipbuilding costs, including costs for nuclear refueling and unmanned systems, would average about $34 billion per year (in 2021 dollars), 10 percent more than the Navy estimated. Annual operation and support costs for the fleet would grow from $74 billion today to $113 billion by 2051.” The bottom line: “The Navy’s total budget would increase from about $200 billion today to $279 billion (in fiscal year 2021 dollars) by 2051.”

Even that is increasingly optimistic, as the services confront the possibility of a year-long continuing resolution (CR). “A year-long CR is completely new territory that we have not dealt with before that will have significant impacts across our military,” Admiral Gilday warned a House Appropriations defense subcommittee hearing in January 2022.19 Gilday said a year-long CR would dangerously delay efforts to replace the Ohio-class ballistic-missile submarines (SSBNs) and upgrade its naval shipyards. “The once-in-a-century work we are doing on our public shipyards will come to a stop,” Gilday said, including on the new Columbia-class SSBNs. Gilday also said a year-long CR would force the Navy to reduce the number of new sailors by 75 percent and halve the number of planned personnel transfers around the fleet.

The Right Mix?

At a 17 June 2021 congressional hearing, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin called 355 ships “a good goal to shoot for” but said he was intent on fielding “the right mix of capabilities. Size matters, but capabilities also matter.”20 To get to the “right mix,” the Navy announced it would decommission 15 ships in FY2022—7 Aegis guided-missile cruisers, 4 littoral combat ships, 1 amphibious assault ship, 2 attack submarines, and 1 fleet tug—while adding 8 manned ships. Highlights of the FY2023 shipbuilding plan overview include:

• Continued funding for the Columbia-class SSBN program

• Full funding for two more Gerald R. Ford–class carriers (CVN-80 and -81)

• Continued funding for the Block V multiyear procurement FY2019 to FY2023 for ten Virginia-class attack submarines, nine of which will have Virginia payload modules

• Procuring one DDG-51 Flight III guided-missile destroyer, totaling 11 Flight III procurements from FY2018 to FY2022

• Planning procurement of one Constellation-class frigate (FFG-62)

• Procuring one John Lewis–class (TAO-205) fleet replenishment oiler

• Procuring a lead T-AGOS(X) ocean surveillance ship in FY2022

• Accelerating the Navajo-class fleet oceangoing tug (T-ATS) program by adding a ship in FY2022

• Continued recapitalization of the surge sealift fleet by adding five used vessels in FY2022

Ballistic-Missile/Guided-Missile Submarines

In January 2022, the Navy had 14 Ohio-class SSBNs. The new Columbia class will replace retiring Ohio-class submarines during the next 20 years. O’Rourke noted, “Navy officials have stated consistently since September 2013 that the Columbia-class program is the Navy’s top priority program, and that this means . . . the Columbia-class program will be funded, even if that comes at the expense of funding for other Navy programs.” The Navy estimates that the submarines will take seven years to build and test, so the Columbia (SSBN-826) would be commissioned in 2028 and go on her first patrol three years later.21

The health of the submarine industrial base also is a concern for both the Navy and industry, especially as that finite base is being hard-pressed to simultaneously execute the Columbia and Virginia programs. “Let’s face it, that supply base is brittle,” Electric Boat President Kevin Graney told Defense News. “I would say our critical suppliers are ready today for the work that we have on our plate,” Graney said. “How we extend that to get to serial production on Columbia, I think, is the next hurdle for us to get through.”22

In 2002–4, the Navy converted the first four Ohio-class SSBNs to a conventional configuration (SSGNs), each capable of carrying as many as 154 Tomahawk land-attack cruise missiles (TLAMs), or fewer missiles when embarking special operations forces. In 2042, the Navy looks to replace the SSGNs with a new-design, large-payload submarine for conventional

missile, special operations, and other covert missions.

Attack Submarines

In early 2022, the Navy had three classes of attack submarines (SSNs) in service. Twenty-eight improved Los Angeles–class submarines, each equipped with 12 vertical launch system (VLS) tubes for TLAMs. The fleet also has three Seawolf-class submarines—exceptionally quiet, fast, well-armed, and equipped with advanced sensors. And as the Navy continues to acquire Virginia-class submarines to replace the aging Los Angeles class, 19 Virginia boats have been commissioned.

Under the December 2020 plan, the Navy would acquire 77 attack submarines during the next 30 years, 16 more than previously planned. In 2034, the Navy intends to begin acquiring 42 new-design attack submarines—the SSN(X). CBO’s assessment of the Navy’s plan assumes SSN(X) submarines would be Seawolf-like submarines. The plan also would extend the service lives of improved Los Angeles–class boats to sustain a force of about 50 or more SSNs over the next 30 years. Otherwise, the attack submarine force would have fallen to 42 in the late 2020s before growing again.23

The surprise September 2021 announcement of an Australian, United Kingdom, and U.S. plan, called AUKUS, to build and provide nuclear submarines for Australia could affect the future evolution of the U.S. SSN(X) program. AUKUS marks the first time the United States has agreed to share nuclear submarine technology with any ally since the 1950s, when the UK was first granted approval. “This technology is extremely sensitive. This is frankly an exception to our policy in many respects,” an unnamed U.S. official said. “We view this as a one-off.”24

Aircraft Carriers

In December 2020, the size, shape, and cost of aircraft carriers were under scrutiny, again. In January 2022, the carrier force comprised ten Nimitz-class nuclear-powered aircraft carriers and the first-of-class Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78). CVNs-79 and -80 also are under construction.25 CBO’s Labs calculated the future carrier force under the December 2020 plan would require six Gerald R. Ford–class carriers between 2022 and 2051. The number of carriers in active service will remain at 11 through 2040, before falling to ten through 2051. Carriers have service lives of 50 years, so to reach and sustain a force of 11 active ships, the Navy would need to acquire one carrier every three and a half years between 2028 and 2051.26

Although Battle Force 2045 called for a study of conventional (non-nuclear- powered) light carriers (CVLs), it does not include acquiring light or so-called Lightning carriers. The June 2021 update also continued support for CVNs but notes that “new capability concepts like a light aircraft carrier continue to be studied and analyzed to fully illuminate their potential to execute key missions.”

Former Navy Secretary John Lehman, who championed the 1986 Maritime Strategy and the 600-ship Navy in the 1980s, has suggested the Navy should consider a new 65,000–75,000 ton, conventionally powered carrier that would be about the size of the post–World War II Midway class. Lehman maintains this design would provide the Navy more options, cost less than nuclear-powered carriers, and help diversify the industrial base.27

This is not new. Since the early 1960s, a gaggle of future carrier studies wrestled with the “big vs. little” and “nuclear vs. oil-fired” dilemma. Approximately 100 aircraft carrier concepts were assessed in two major studies—the Sea-Based

Air Master Plan and the Assessment of Sea-Based Air Platforms Study. At least since 1975, big and nuclear-powered carriers, complemented with big-deck amphibious ships, have been what the Navy has bet on.

Large Surface Combatants

“Decades ago,” CRS analyst O’Rourke recounted, “the Navy’s cruisers were considerably larger and more capable than its destroyers. In the years after World War II, however, the Navy’s cruiser designs in general became smaller while its destroyer designs in general became larger.” As a result, since the 1980s there has been substantial overlap in size and capability of Navy cruisers and destroyers. The Navy’s Zumwalt-class destroyers are, in fact, considerably larger than its cruisers.28

In late 2021, the Navy’s large surface combatant force numbered 92 warships—22 Ticonderoga-class guided-missile cruisers and 70 Arleigh Burke–class guided-missile destroyers. CBO’s Labs explained, “The December 2020 shipbuilding plan calls for 55 new destroyers, 21 fewer than the previous plan. That change is consistent with the FNFS objective to reduce the proportion of large surface combatants in the fleet.”

The Navy procured three Zumwalt-class destroyers in FY2007–FY2009 and plans no further procurement. Navy officials now envision equipping the class with the Conventional Prompt Strike hypersonic missile and removing the ship’s 155-mm gun turrets to make room for this advanced capability. Hypersonic missiles also will require the Advanced Payload Module launcher technology.29

Prior to 2020, the Navy had intended to extend the service lives of all Arleigh Burke–class destroyers to 45 years. “In the spring 2020,” according to the CBO, “the service discarded that idea, citing the high cost of maintaining and operating older ships. The Navy now expects that DDG-51s will serve for 35 or 40 years depending on their flight, or variant. The first 28 DDG-51s—Flights I

and II—would serve for 35 years; the later ships—Flights IIA and III—would serve for 40 years.”

The 2016 shipbuilding plan also showed a new-design DDG(X) guided-missile destroyer funded in 2025. The December 2020 plan delayed the first DDG(X) until 2028. According

to the Navy, DDG(X) will have combat systems like those on board the DDG-51 Flight III destroyers but will have a larger hull, more power, and more cooling.

Small Surface Combatants

The Navy’s active small surface combatant force comprises littoral combat ships (LCSs) and eight Avenger-class mine countermeasures ships. Thirty-five Freedom monohull and Independence trimaran hull LCS variants have been delivered to the fleet, are in construction, or are under contract. The numerous problems with the early LCS variants convinced Pentagon leaders to reduce the buy from an original 52 to 35 ships, and the Navy retired the first two hulls of each variant in 2021.30

There are no plans to acquire dedicated MCM ships to replace the Avengers. Instead, the Navy has been developing MCM mission modules to be deployed on board LCSs and other ships, and even from shore facilities.

The Navy stopped delivery of Freedom variants in 2021 following the discovery of a latent defect in the ship’s complicated combining gear machinery. Land-based testing followed by at-sea testing on board the USS Minneapolis-St. Paul (LCS-21) using a different bearing in the combining gear seems to have fixed the issue, and the Navy has resumed accepting delivery of Freedom variants. Plans for fixing the defect on already-delivered LCSs remain in flux.31

Following a year-long competition, the Navy awarded a contract to design and build the first ten next-generation Constellation-class guided-missile frigates. Navy plans call for building 20 frigates in total, with the second ten to be competed with a second shipyard. CBO noted that under the December 2020 plan, the service also would acquire 51 small combatants of an undetermined design.

Amphibious Warfare

The Navy’s 2022 amphibious warfare force includes 32 large ships—9 amphibious assault ships (LHAs or LHDs), 11 amphibious transport docks (LPDs), and 12 dock landing ships (LSDs). The 9 December 2020 plan has the Navy acquiring 16 large amphibious ships (LHAs and LPDs), 12 fewer than under the FY2020 plan. The CBO has the Navy standing up a major building program for smaller light amphibious warfare ships (LAWs). In 2020, Congress funded the LHA, and 36 LAWs would be acquired between 2022 and 2038. Because the LAWs would have only 20-year service lives, the Navy would start buying replacements in 2042, ultimately acquiring 55 LAWs.32

Marine Corps leaders have emphasized the need to diversify the current inventory of amphibious ships as part of their Force Design 2030 efforts. LHAs, LHDs, and LPDs are all great platforms with good capabilities, but the amphibious force of the future requires more ships on the lower end of the capability spectrum. “Those three families of pretty expensive, high-end ships are not enough. We need a more diverse family of ships in order to compete every day. . . . We know we need something that’s smaller, that doesn’t have as much draft, that can move us around from ship to shore or shore to shore over great distances, but is affordable,” Marine Corps Commandant General David H. Berger said in a September 2021 forum.33

The June 2021 update described the LAW as “an enabler of [Marine Littoral Regiment] mobility and sustainability. The overall number of amphibious warships grows to support the more distributed expeditionary force design, with LAWs complementing a smaller number of traditional amphibious warships.” According to the CRS, “as conceived by the Navy and Marine Corps, LAWs would be much smaller and individually much less expensive to procure and operate than the Navy’s current amphibious ships. The Navy estimates that the first LAW would cost about $156 million to procure, and that subsequent LAWs would cost about $130 million each to procure.”

A 17 June 2021 long-range Navy shipbuilding document envisions procuring a total of 24 to 35 LAWs, while other Navy documents refer to a requirement for 35 LAWs. This has the Navy meeting its minimum inventory goal of 61 amphibious ships by 2040. However, the number of large amphibious ships would fall to around 26 by 2024.

Unmanned Platforms and Systems

“In the years since the 2016 FSA,” O’Rourke noted, “the Navy has developed plans to acquire large USVs and UUVs. Because of their size and projected capabilities, these large UVs are to be deployed directly from pier, rather than from manned ships, to perform missions that might otherwise be assigned to manned ships and submarines. In view of this, some observers have raised a question as to whether these large UVs should be included in the top-level expression of the Navy’s next force-level goal . . . and the publicly cited figure for the number of ships in the Navy. Department of Defense officials since late 2019 have sent mixed signals on this question, but in September 2020 indicated that the Navy’s next force-level goal will include large UVs.”34

CBO’s Labs explained, “Unlike the Navy’s FY 2020 shipbuilding plan, the new plan would incorporate large numbers of unmanned undersea and surface vehicles into the fleet. The FNFS included inventory goals of 119 to 166 unmanned medium surface vehicles (MUSVs) and large surface vehicles (LUSVs) and 24 to 76 extra-large unmanned undersea vehicles (XLUUVs), for a total of 143 to 242 systems. The LUSVs would operate in conjunction with other ships, carrying offensive and defensive missiles that manned ships could employ as needed. MUSVs would serve as sensor or command-and-control platforms, providing information about opponents to other ships in the Navy’s fleet. Although the Navy’s plan is less specific with respect to XLUUVs, they could carry a variety of payloads to support naval operations. The Navy is still developing its concepts of operations for unmanned systems, which increases the risk for both cost growth and delays in their construction and operations.”

To accelerate the service’s knowledge and understanding of USVs, the Navy is growing an experimental fleet of prototypes operated by the Surface Development Squadron based in San Diego. The Sea Hunter and Seahawk prototypes are engaged in exercises and at-sea experiments and the Navy has taken delivery of two of four USVs funded by the Pentagon’s Strategic Capabilities Office. The Navy also has funded the first medium USV, which is being built by L3Harris. “Not only are we demonstrating increasingly capable unmanned surface vehicle technology, but we are rapidly advancing the Navy’s ability to conduct extended unmanned surface vehicle operations via a remote-control interface,” according to Captain Pete Small, program manager for unmanned systems in Program Executive Office Unmanned and Small Combatants.35

Combat Logistics Force and Support Ships

Combat logistics ships operate with or directly resupply combat ships at sea. According to the CBO, under the December 2020 plan the Navy would fund 104 new combat logistics and support ships, 47 more than under the previous plan. It would acquire 38 large combat logistics ships—22 T-AO oilers and 16 T-AKE dry cargo ships—and 42 new-design, smaller T-AOL oilers to support a larger fleet with a greater proportion of smaller ships. “Of the 24 support ships, nine would be large ships (2 tenders, 2 command ships, 2 expeditionary transfer docks, 2 AKEs for the Navy’s maritime prepositioning squadrons, and 1 expeditionary sea base) . . . and 15 would be new-design small ships (7 surveillance ships, 6 expeditionary fast transports, and 2 salvage/fleet tugs).” The Navy procured its first John Lewis–class oiler in FY2016, and a total of six have been procured thus far, including the fifth and sixth in FY2020. The Navy wants to procure a total of 20 TAO-205s.

The Navy’s Next-Generation Logistics Ship (NGLS) program envisages procuring a new class of medium-sized at-sea resupply ships. The Navy’s proposed FY2022 budget requests $27.8 million in research-and-development funding for the program. The issue for Congress is whether to approve, reject, or modify the Navy’s proposed funding requests and emerging acquisition strategy for the NGLS program. Congress’s decisions on this issue could affect Navy capabilities and funding requirements and the U.S. shipbuilding industrial base.

TAGOS ships support Navy antisubmarine warfare (ASW) operations. As stated in the Navy’s FY2021 budget submission, TAGOS ships “use the Surveillance Towed-Array Sensor System (SURTASS) to gather undersea acoustic data. They also carry electronic equipment to process and transmit that data via satellite to shore stations for evaluation.” The Navy wants to procure in FY2022 the first of a planned new class of seven ocean surveillance ships (TAGOS(X)). The Navy’s proposed FY2022 budget requests $434.4 million for the procurement of the first TAGOS(X).36

Tough Choices Ahead

The Navy confronts numerous fleet-architecture courses of action in early 2022 and beyond. Selecting one and seeing it through the inevitable changes in political and military leaders and shifting strategic frameworks and guidance will determine how successful the Navy is at growing the current fleet. Admiral Gilday stated, “The long-term global maritime contest we face today requires us to adopt competitive and sustainable approaches to deliver the Integrated All-Domain Naval Power America needs to win. The decisions and investments we make this decade will set the maritime balance of power for the rest of this century. We can accept nothing less than success.”37

As Representative Luria challenged, “It is this exceptional power––and responsibility––that requires exceptional thinking by the political and military leaders of our nation. This global maritime strategy can work, but the Navy will have to overcome substantial barriers to change in the Joint Staff, Combatant Commands, amongst the Services, and within the National Security Council, and Congress. However, one cannot argue with a good plan. All we need is the plan and a few champions on Capitol Hill.”

Stand by for Advantage at Sea Revision 2023, 2024, etc.

1. Samuel Huntington, “National Policy and the Transoceanic Navy,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 80, no. 5 (May 1954).

2. Erik Gartzke and Jon Lindsay, “Strategic Tradeoffs in U.S. Naval Force Structure—Rule the Waves or Wave the Flag?” War on the Rocks, 3 March 2021.

3. HON Elaine Luria, “A New U.S. Maritime Strategy,” CIMSEC, 12 July 2021. See also Loren Thompson, “Sizing the Navy: Why It Takes More Warships to Prevent Conflicts than to Win Them,” Forbes, 10 August 2021.

4. Richard Burgess, “Admiral: New Maritime Strategy’s ‘Control of the Seas’ Compares Well to Cold War Maritime Strategy,” SeaPower Magazine, 17 December 2020.

5. RADM James Bynum, USN, “Advantage at Sea: A Discussion on the Recently Released Tri-Service Maritime Strategy by the U.S. Navy, U.S. Marine Corps, and U.S. Coast Guard,” Oxford Talks, March 2021.

6. Jonathan Caverley and Sara McLaughlin Mitchell, “A Liberal Case for Seapower?” War on the Rocks, 25 February 2021.

7. Paul van Hooft, “Don’t Knock Yourself Out: How America Can Turn the Tables on China by Giving Up the Fight for Command of the Seas,” War on the Rocks, 23 February 2021. See also, Ronald O’Rourke, U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas: Background and Issues for Congress, 21 December 2021 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service).

8. Evan Montgomery, “Defense Strategy and the Empire State of Mind: How Preparing for the Best Can Leave Washington Vulnerable to the Rest,” War on the Rocks, 19 February 2021.

9. Caverley and Mitchell, “A Liberal Case for Seapower?”

10. Michael Sinclair, Roderick H. McHaty, and Blake Herzinger, Implications of the Tri-Service Maritime Strategy for America’s’ Naval Services, March 2021 (Washington DC: Brookings Institution).

11. Department of Defense news release, “DoD Concludes 21 Global Posture Review,” 29 November 2021; Heather Mongilio, “Pentagon Announces Completion of Global Posture Review,” USNI News, 29 November 2021.

12. Mallory Shelbourne and Sam LaGrone, “Pentagon, Navy Conducting Parallel Fleet Studies Ahead of Next National Defense Strategy,” USNI News, 21 September 2021.

13. Mongilio, “Pentagon Announces Completion of Global Posture Review.”

14. Ronald O’Rourke, Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issue/s for Congress, 9 December 2021 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research); O’Rourke prepares other CRS reports on specific programs. For a summary indictment of the combatant commander–centric approach, see ADM James G. Foggo, USN (Ret.), “Forward Naval Process: A Political, Not Military, Leadership Problem,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 148, no. 1 (January 2022).

15. Megan Eckstein, “CNO: Pentagon Global Posture Review Will Inform Future Carrier Missions, Arctic Presence,” USNI News, 29 November 2021.

16. Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2022, June 2021 (Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, Deputy Chief of Naval Operations Warfighting Requirements and Capabilities—OPNAV N9).

17. Brent Sadler, “U.S. Navy” Section in 2022 Index of US Military Strength, 20 October 2021 (Washington, DC: The Heritage Foundation).

18. Bradley Peniston, “U.S. Navy’s Latest Plan for its Future May Not Come Until 2023,” Defense One, 24 September 2021.

19. Marcus Weisgerber and Tara Copp, “Military Chiefs Sound Alarm at Proposal to Hold 2022 Spending to Last Year’s Level,” Defense One, 12 January 2022.

20. Martin Manaranche, “U.S. Navy Issues FY22 Shipbuilding and Decommissioning Totals to Congress,” Naval News, 18 June 2021. The shipbuilding discussions also rely on the various Congressional Research Service issue briefs and reports, U.S. Naval Systems Command Fact-Files, and the Naval Vessel Register.

21. Ronald O’Rourke, Navy Columbia (SSBN-826) Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program: Background and Issues for Congress, 8 December 2021 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service).

22. Megan Eckstein, “U.S. Navy Avoided a ‘Trough’ in Submarine Fleet Size, But Industry Challenges Threaten Future Growth,” Defense News, 3 January 2022.

23. Ronald O’Rourke, Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Program: Background and Issues for Congress, 8 December 2021 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service); In Focus: Navy Next-Generation Attack Submarine (SSN[X] Program: Background and Issues for Congress, 9 December 2021 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service).

24. Jacqueline Feldscher, “Australia Will Get Nuclear Powered Subs in New Partnership with US, UK,” Defense One, 15 September 2021.

25. Ronald O’Rourke, Navy Ford (CVN-78) Class Aircraft Carrier Program: Background and Issues for Congress, 8 December 2021 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service).

26. The carrier force dropped from 11 ships to 10 ships between 1 December 2012, when the USS Enterprise (CVN-65) was inactivated, and 22 July 2017, when the USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) was commissioned. Anticipating the gap between the inactivation of CVN-65 and the commissioning of CVN-78, the Navy asked Congress for a temporary waiver to accommodate the period between the two events. The FY2010 National Defense Authorization Act authorized the waiver, permitting the Navy to have ten operational carriers.

27. John F. Lehman and Steve Wills, “Where Are the Carriers? U.S. National Security and the Choices Ahead,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, 9 September 2021.

28. Ronald O’Rourke, Navy DDG-51 and DDG-1000 Destroyer Program: Background and Issues for Congress, 8 December 2021 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service); In Focus: Navy DDG(X) Next-generation Destroyer Program: Background and Issues for Congress, 9 December 2021.

29. Peter Ong, “Latest Details on Hypersonic Missile Integration Aboard Zumwalt-Class Destroyers,” Naval News, 28 October 2021.

30. Ronald O’Rourke, Navy Constellation (FFG-62)-Class Frigate Program: Background and Issues for Congress, 8 December 2021 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service).

31. Sam LaGrone, “Littoral Combat Ship Minneapolis-St. Paul Delivers to Navy after Combining Gear Fix; Navy Resumes Delivery of Freedom Class,” USNI News, 18 November 2021.

32. Ronald O’Rourke, Navy Light Amphibious Warship (LAW) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, 9 December 2021 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service).

33. Richard Burgess, “Berger: Marine Corps Needs More Diversity—In Amphibious Ships,” Seapower Magazine, 24 September 2021.

34. Department of the Navy, Unmanned Campaign Framework, 16 March 2021.

35. Megan Eckstein, “Navy to Expand Land-Based Testing for Unmanned Vessels, Conduct Offensive Firepower Analysis for USVs,” USNI News, 25 January 2021.

36. Ronald O’Rourke, Navy John Lewis (TAO-205)- Class Oiler Shipbuilding Program: Background and Issues for Congress, 9 December 2021 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service); Navy TAGOS(X) Ocean Surveillance Shipbuilding Program: Background and Issues for Congress, 22 December 2021 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service); In Focus: Navy Next-Generation Logistics Ships Program, 22 December 2021 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service).

37. ADM Michael M. Gilday, USN, CNO NAVPLAN, January 2021.