Compared to typical labor markets, retention is of particular importance to the Navy because its active-duty personnel system is one in which virtually all hiring is entry level and all promotions come from within the existing force. The loss of a skilled individual is acute given that the Navy must “grow” a replacement from within. Retention of optimally placed service members can alleviate time lags and mismatches between job requirements and job openings, while also saving money and boosting fleet performance.

As the nation’s demographics become increasingly diverse, the Navy’s talent will come from increasingly diverse sources. As Admiral John Richardson, former Chief of Naval Operations, stated, “Achieving top performance is enhanced when leaders tap into the energy and capability of an actively inclusive team.”1

As of 2015, Naval Academy graduates comprised roughly 20 percent of commissioned officers in the Navy and Marine Corps, although the number of female graduates is disproportionately smaller.2 In research conducted by the authors, more than 6,000 Naval Academy graduates from 1980 (the first class with women) through 2016 answered a series of questions relating to their lives before, during, and after the Academy.3 By matching the survey sample to administrative records collected by the Naval Academy, statistical analysis demonstrates that respondents are representative of all graduates. The data sheds light on factors that may explain the gender gap in length of service (LOS) and enhances the Navy and Department of Defense’s (DoD’s) understanding of how to “remain competitive and an employer of choice” for “talent in the global market.”4

At the Naval Academy, women were 27 percent of the Class of 2021.5 Like all midshipmen, they were immersed in a program designed to give all graduates a similar educational and leadership background. Yet, career outcomes differ substantially for male and female graduates. While many institutional barriers for women have been broken, female officers in the Navy and Marine Corps exit the service at higher rates than their male counterparts. For example, for the survey respondents from the class years 1988–2000, male graduates served on active duty for an average of 12.7 years while women served 10.3 years.6 The experiences of women from the Naval Academy may help DoD better understand past and present factors that determine the retention of women in the service.

A central question underlying this analysis is whether these gaps in LOS are driven primarily by “push from the Navy”—structural factors within the Navy that might compel women to exit earlier than men—or by the “pull of the private sector”—economic and social factors that make opportunities outside the Navy and Marine Corps more attractive.

Data and Analysis

The goal of this research is to help understand female retention in the Navy and Marine Corps. It begins with a retrospective question from the survey: whether respondents wanted to make the military a career at different points before and during their time at the Academy. Female Naval Academy graduates at each point reported being significantly less enthusiastic about that likelihood than their male counterparts, although both groups started out lower than expected.

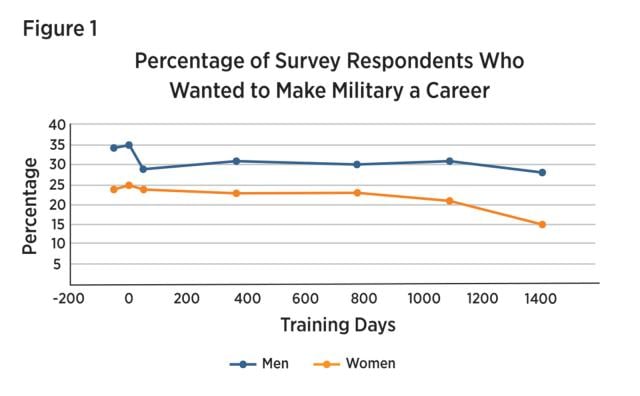

Figure 1 illustrates the percentage of survey respondents who expected to stay for a career at seven major checkpoints, starting with their decision to attend the Naval Academy (approximate training day T= -100—100 days before arrival at the Academy). The second milestone (T=0) is the first day at the Academy—known as “I-Day”—when incoming midshipmen start their freshman (or plebe) year with a seven-week indoctrination course called “plebe summer.” The remaining milestones are: the end of plebe summer (T=50); the end of plebe year (T=365); the “2 for 7 signing” (T=780)—a milestone halfway through midshipmen’s time at the Academy when they can leave or sign on for seven more years of naval service—the beginning of senior (or first class) year (T=1,100); and, finally, at commissioning and graduation (T=1,400).

Men had a higher expectation to serve a career compared with women at each milestone. While both trendlines decline as midshipmen get further into their time at the Academy, on graduation only 15 percent of female respondents cited a desire to serve out a career compared with 28 percent of male respondents. Although both trend lines generally decline, the line for women falls off somewhat more sharply toward the end of their time at the Academy.

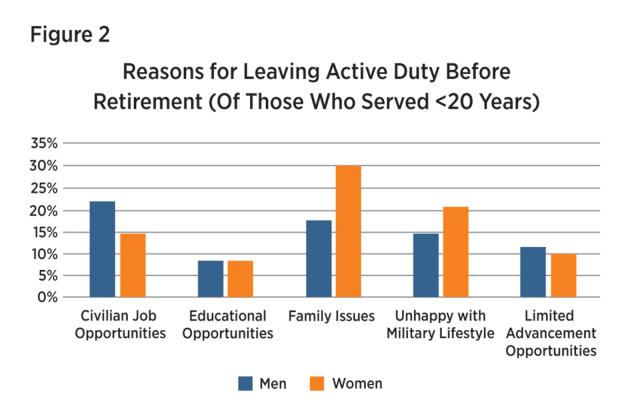

In addition, total years of service broken down by each major service assignment in the Navy and Marine Corps helps illuminate the gender gaps for officer retention. To remain consistent, this analysis is limited to the classes of 1988–2000, to capture only those who could have served a sufficiently long career at the time the survey was administered in 2019–20.7 Figure 2 illustrates that female graduates serve fewer years than male graduates in all major assignment categories except for “other,” a category that includes noncombat staff positions such as human resources, medical occupations, supply fields, and other restricted line billets.

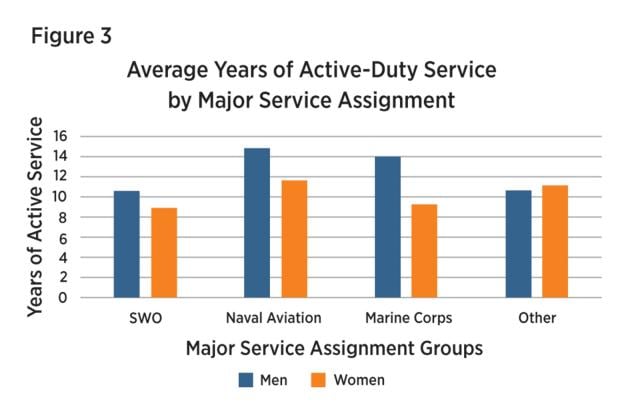

To identify possible reasons for these findings, Figure 3 shows the five most cited reasons in the survey for graduates to leave active duty before retirement. The first two (civilian job opportunities and educational opportunities) are “pull” factors, while the last three are “push” considerations, in which structural features of naval service compel officers to depart. The data shows women’s reasons for departures are starkly different from those of men. More than 50 percent of women cited family issues and military lifestyle (push factors) as reasons for leaving active duty prior to retirement, compared with less than 35 percent of men. On the other hand, of the men who departed prior to retirement, more than 20 percent cited civilian job opportunities (pull factors) as a reason, compared with 15 percent of women. Family planning and quality of (family) life considerations are clearly causes underlying lower retention of women.

There also are striking differences in Naval Academy graduates’ family composition by gender: 16 percent of men reported having zero children compared with 40 percent of women. Here, the sample is limited to respondents who were still on active duty at the time they took the survey, to better capture family planning decisions of those still affected by Navy/Marine Corps policies. Active-duty female officers are far less likely to have children than men, and, furthermore, among those who do have children, they are likely to have fewer. Specifically, among active-duty officers with at least one child, men on average have 2.3 children while women have 1.8.

Breaking down the number of children by gender and rank, even more stark contrasts are observed at the senior officer level. For example, among those who reached the rank of O-6 or higher, only 7 percent of men reported having no children, as opposed to 24 percent of women. This paints an even clearer picture: Female officers who built long careers in the Navy or Marine Corps are far less likely to have children. Furthermore, women who attained O-6 or above are more likely to forgo marriage; the survey shows that only 6 percent of men never married, compared with 16 percent of women.

DoD must address the challenges of family life with career development in the Navy and Marine Corps. If left unaddressed, these challenges will lead to more talent lost to the private sector, particularly as corporate America continues to improve parental leave and other related benefits for both women and men. The services can no longer afford to put women in the position of feeling as if they have to choose between family and service.

One final empirical observation highlights the importance and potential intractability of the retention issue, should it remain unaddressed. The survey asked graduates to assess how important the Naval Academy’s diversity and inclusiveness were to their decision to attend the institution. Only 12 percent of men held these factors to be somewhat important while 4 percent saw it as very important. These proportions were twice as large for women. Thus women, as they weigh the decision to attend the Naval Academy and eventually accept a commission into the Navy or Marine Corps, value diversity more than men. When viewed alongside the Navy and Marine Corps’ longstanding female retention challenges, this observation points to a trap in which the failure to retain women likely makes it more difficult to recruit women to the Naval Academy.

Policy Recommendations

In 2016, DoD made two major policy changes bearing on the retention of women. First, maternity leave was increased from 6 to 12 weeks. Second, dual-military spouses were required to be co-located within 90 miles of each other’s duty station given billet availability—a policy that affects only a small share of military families and would need to be expanded if DoD/Navy intends to support family-friendly careers. Any effects stemming from these policies, given their recency, are not reflected in the data. These changes are steps in the right direction, and the statistics and metrics discussed above should be used to assess their success or failure. But, given the intractability and scope of the retention issue, DoD should do more.

For the Naval Academy, leaders should fill billets with more senior female officers, particularly for visible and pivotal assignments. Most notably, to date, the Academy has never had a female Superintendent and only one female Commandant of Midshipmen. There are many other crucial, visible billets, such as battalion officers, senior female officer instructors, and recruiters, that should become more gender balanced. Extensive economic and military research stresses the importance of mentorship in encouraging minorities to pursue certain career paths and remain on active duty longer. Relatively low senior female officer presence at the Naval Academy likely inhibits female midshipmen’s ability to “see themselves” as among those officers who are on a path to a 20-year career. Because the Academy provides a relatively large number of officers to the service, it might be worthwhile to use it as a location to test the hypothesis that an increased complement of female training officers can have a salutatory effect on the career expectations of female officers-in-training.

Two other broad policy recommendations arose from discussions of the survey’s findings with those who have operational and administrative experience. First, it likely will be many years before there will be a critical mass of women in senior positions in the Navy and Marine Corps, but the mind-set that men stand first in line for important/promotable jobs must be debunked. Unfortunately, given historical norms, there are many positions that women are unlikely to be selected for or will be reluctant to pursue. In this regard, men who are in positions of command must seek to fill major career “stepping-stone” billets in ways that are gender blind. Talent for the task should be the foremost consideration. Men can undertake more mentoring and role model initiatives, serving at a minimum as backups to the efforts of senior women.

Second, the findings point to the need for the naval service to initiate a “family track” that is designed to retain talented service members of both genders. Several retention policies already exist; for example, the Navy supports higher educational attainment in return for additional years of service. Such policies could serve as a model for new, manageable programs directed at retention of female officers.

Although different policies may be needed for the various service communities, consideration should be given to expanded sabbatical opportunities, leaves of absence, locational stability options, and even job-sharing, in return for extensions of active-duty time and/or flexibility around the 20-year career retirement standard. The Navy and Marine Corps should implore both genders to take advantage of such opportunities, including leave opportunities that are granted to new parents.

Finally, further research is needed into these retention challenges. Undoubtedly there are other gender-gap issues that have the potential to improve retention of women in the Navy, Marine Corps, and DoD. Policies based solely on the use of exit interviews, however, may be suspect, as one reviewer noted, because women may be unwilling to state in a formal interview that “the real reason [they left is because they never felt] they truly ‘belonged.’” One female senior officer commented that “there are multiple stories from women who were treated horribly.” While divisive attitudes likely have ebbed over the years, their perpetuation remains supported by this data analysis. The combination of impactful reforms and meaningful, lasting advances in societal norms, both within and outside DoD, are necessary to realize enduring change.

1. ADM John M. Richardson, USN, “One Navy Team,” Department of Defense, 27 September 2016.

2. Scott Beauchamp, “Abolish West Point—And the Other Service Academies, Too,” Washington Post, 23 January 2015.

3. ENS Jatin Khona, USN, Michael A. Insler, and Roger D. Little, “Gender and Career Outcome Differentials Amongst Officers in the United States Navy and Marine Corps,” Economics Department, U.S. Naval Academy (May 2021).

4. U.S. Department of Defense, Department of Defense Diversity and Inclusion Strategic Plan 2012-2017 (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 20 April 2012).

5. “Class of 2021 Statistics,” U.S. Naval Academy, 7 July 2017.

6. This topic is explored in greater technical detail in Khona, Insler, and Little “Gender and Career Outcome Differentials.” Comparable analyses observe the same findings while controlling for a host of characteristics such as class year, race, service community, family military history, academic and military GPAs, SAT scores, athlete status, prior enlisted, age entering the Naval Academy, public/private high school, family socioeconomic status, and personality metrics.

7. Assignment to submarines is not included in this graph because the first women served on submarines starting in 2010.