Know your job. That was the first leadership lesson I learned when I reported to my first ship as a surface warfare officer (SWO) in training. Sailors, I quickly realized, will trust you until you give them a reason not to, and nothing will obliterate their respect for their chiefs and officers faster than finding they lack expertise. Unfortunately, that is the position the Navy puts first- tour division officers in: asking them to lead engineering divisions after a measly few weeks of PowerPoint-based classes at the Basic Division Officer Course. Why not create a corps of engineering officers distinct from the surface warfare officers who drive the ships?

SWOs today do not see themselves as mariners or engineers, but rather as generalists. As they advance in rank and eventually become commanding officers of ships, they believe they are better off knowing a little about everything rather than specializing in any one thing, be it engineering, communications, navigation, or warfighting. However, if the accidents in the surface force have taught the Navy anything, it is that today’s SWOs are overworked and undertrained, and in trying to be good at everything, they have become experts at nothing.

The service can start to solve this problem by separating mariners and engineers in its wardrooms. To try to be both is a burden no officer, let alone a brand new ensign, should have to shoulder.

Officers will have a difficult time being good leaders if they are not skilled at what they do. It is not fair to hand a binder full of qualifications to young ensigns reporting to their first ships, put them in charge of real sailors and real equipment, and say, “Figure it out.” The idea that chief petty officers will tram them also is misguided. Chiefs do not have enough time to devote to their division officers, and the hierarchy of rank is turned upside down if subordinates must hold their superiors’ hands as they do their jobs.

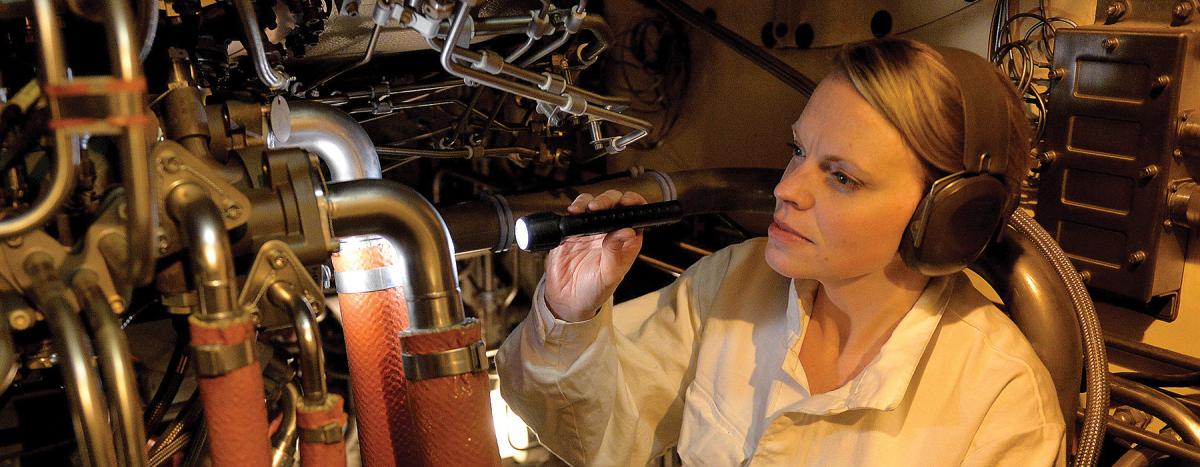

Ships’ engineering plants, with their high potential for mishap, require special attention and proper leadership. Today, though submarines and aircraft carriers benefit from a corps of highly trained engineering officers, surface ships largely lack qualified officers in their engineering departments.

The Royal Navy offers a model for a two-track system, as its surface officer corps is divided into engineering and warfare. More important, the British have a rigorous training program for officers to learn their craft in either field before they are ever put in charge of sailors. The U.S. Navy should do the same. This would further specialize officers on board ships and allow the Navy to seek and train more qualified individuals. And taking bridge watch and navigation qualifications off the shoulders of engineering officers would allow them to devote more time to their sailors and their divisions. In the long term, this would create more competent leaders and prevent the micromanaging style fleets and squadrons have adopted to inspect their ships’ engineering plants

Since the tragedies of the USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62) and John S. McCain (DDG-56), the Navy has taken small steps to improve standards in the surface warfare community. Yet, ask SWOs today, and most will admit that the surface warfare culture and training model are in need of serious reform. Splitting the community into two specialized fields—one comprised of mariners and one of engineers—is a logical start to solving current problems.