Greenland is a semiautonomous region of the Kingdom of Denmark. The world’s largest island, it is three times the size of Texas. With a population of only 56,600, it also is the most thinly populated “nation” in the world.

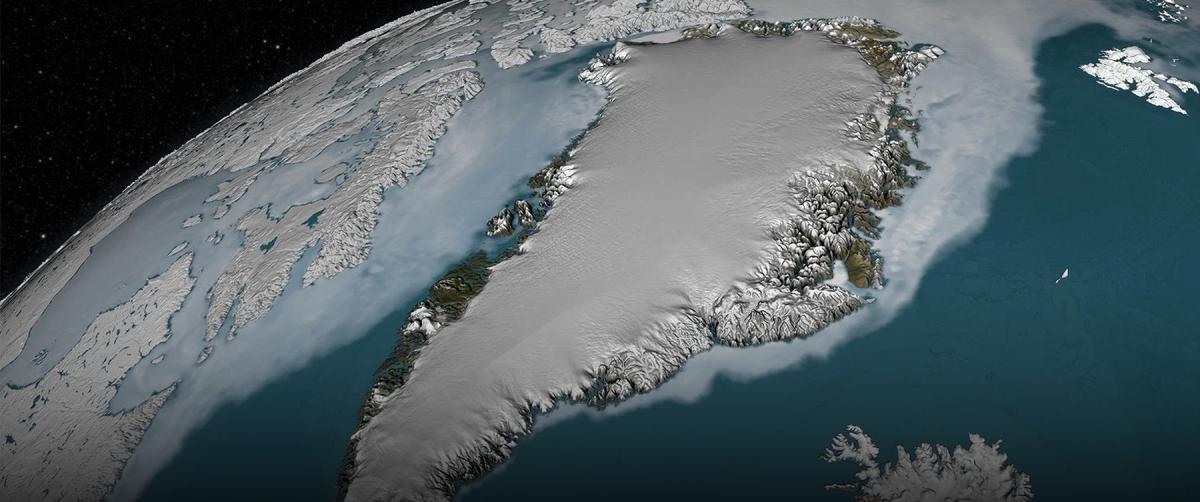

The last time it was ice free and green was about 1.5 million years ago. Since then, 80 percent of its surface (660,000 square miles) has been permanently covered by a sheet of ice up to two miles thick. After the Antarctic, Greenland has the second-largest on-land ice field on the planet. It contains 8 percent of Earth’s fresh water.

A brief exception to the permanent cold was the Medieval Warming Period from 800 to 1200 CE, when many of the southwestern coastal areas became warmer and relatively ice free. Robust vegetation then covered several valleys, a perfect setting for colonization.

In 985 CE, the Viking leader Erik the Red brought 500 pioneers from Iceland to the new land. To help recruit the settlers, he named the place “Green Land.” Eventually, the colony’s population was between 2,000 and 3,000 people living on 300–400 farms. According to contemporary historical accounts, the colony did well until the Little Ice Age began in 1300, when colder weather made the colonists’ lives increasingly difficult. Then, after 500 years of residency, the colony population disappeared in one of history’s great mysteries.

Until the early 1990s, Greenland’s seasonal ice loss was replaced during the winter months with little, if any, annual net loss. However, for the past 25 years, the massive ice sheet has been slowly melting away. It is estimated that if all Greenland’s ice melted, the global sea level would rise about 23 feet. While that would take place over a millennium, even only a few feet of sea level rise would have created catastrophic consequences for low-lying coastlines worldwide.

Sea level rise has three major contributors: ocean warming (water expands when it is heated), Antarctic melting (not a major factor at present), and Greenland melting. Until recently, ocean warming was the major cause. Today, ice loss from Greenland accounts for two-thirds of sea level rise—an estimated one-third of an inch per decade. This rate could easily increase, because scientists have consistently underestimated the nonlinear rate of climate change.

Global climate change is responsible for this seemingly irreversible situation. Overall, the Arctic region is warming three to four times faster than the rest of the planet. At the surface of the ice sheet, overlying warm air melts the ice and, as a result, flowing water percolates though the layers of ice to the rocky substrate below. There, it serves as a lubricant to facilitate faster movement of the ice downslope to the edge of the island. At the same time, the warming ocean water washing against the footings of glaciers along the coast accelerates calving of icebergs launched into the sea.

The numbers for ice loss are huge. Over the past quarter century, the average annual loss has been 308 billion tons of ice and fresh water that flows into the ocean. While some years it is more and others less, there is always an annual net loss. It has been calculated that just 20 years’ worth of Greenland’s meltwater could cover the entire United States with a layer of fresh water one-and-a-half feet deep.

While the annual rate of sea level rise may seem very small, by 2100 it will be sufficient to cause many populated coastal areas worldwide to be flooded and eventually abandoned. This is not a minor problem, as these areas are where more than 20 percent of the world’s population lives. An example is Florida, where scientists estimate the lower third of the state will be completely submerged by the end of this century. While that is nearly eight decades from now, many people born this year will be alive to witness those changes.

Another major concern is that the massive infusion of fresh water into the ocean will adversely affect the strength and direction of some currents. For example, the Gulf Stream could be severely weakened or even stopped. If that happened, there would be cascading climatological effects in the lands flanking the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans.

The future will be very challenging as rising seas continue to encroach on the world’s coastal areas. Infrastructure and populations will have to relocate, and it is not a question of if but when.