China’s coast guard and maritime militia have mounted what essentially is an insurgency in the East and South China Seas for nearly 15 years, building artificial maritime features, blocking access to fishing areas, intruding into neighbors’ waters, and occupying disputed islands. This gray zone campaign at sea and ashore has brought China into tension with Indonesia, Japan, Taiwan, Vietnam, and the Philippines and helped Beijing set the terms of each confrontation.1

Since the end of the Cold War, the U.S. military has planned its forces against “worst-case” scenarios with regional powers such as Iraq, Iran, North Korea, and Russia.2 The Department of Defense (DoD) has continued using that approach regarding China, focused on a full-scale invasion of Taiwan. But with a significant advantage in the military balance, proximity to contested areas, and a comprehensive national military on par with the United States, China has a range of options for taking control of Taiwan.

Instead of pursuing a risky invasion of Formosa, leaders in Beijing are more likely to ramp up their insurgent tactics by seizing outlying islands, conducting cyberattacks or economic warfare, blockading Taiwan, or establishing a quarantine as the United States did against Cuba during the 1962 missile crisis.3 These protracted and lower-intensity campaigns would stress the capacity of U.S. and allied militaries, especially naval forces, and require less escalatory capabilities that do not enable the Chinese government to portray the United States as an aggressor. These tactics also would offer a more gradual transition from today’s gray zone, enabling China to increase the pressure on Taiwan without a defining event that could trigger a full-scale U.S. or allied response.

The United States and its allies have been preparing for a goal-line stand against a Chinese invasion of Taiwan while their opponents in Beijing have assembled a diverse playbook that circumvents the U.S. military’s strengths and exploits its vulnerabilities. To deter China, the U.S. Navy instead will need to address the full range of China’s options by directly undermining the strategy and processes at the heart of People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and Chinese government decision-making.

U.S. Navy ‘Death Stars’ Will Play into China’s Hands

Today’s U.S. Navy is not structured for protracted campaigns in contested areas such as the South and East China Seas. Large force packages such carrier strike groups (CSGs) that can defend themselves against the PLA’s substantial missile capacity are costly to build and operate, constraining the number that can be sustained on deployment. Individual platforms such as littoral combat ships (LCSs) or guided-missile destroyers are less expensive but are manned and not numerous enough to be attritable. As a result, they would need to be protected or move to more permissive areas when a gray zone confrontation turns to combat, constraining the options available to U.S. commanders and making their operations more predictable.

PLA doctrine is designed to exploit the anticipated approaches used by U.S. forces. Under the concept of “systems warfare,” PLA leaders build systems and plans to attack key vulnerabilities of an adversary’s expected tactics and capabilities.4 For example, the PLA’s system of systems for missions such as information confrontation and firepower strike are built to undermine U.S. power projection by amassing salvos that compel U.S. forces to aggregate for self-defense and operate from farther away, while degrading the communications U.S. commanders need to coordinate with headquarters at those longer ranges.

The PLA’s emphasis on systems warfare derives in part from its “home team” advantage. China’s proximity to likely areas of conflict such as the Taiwan Strait or disputed areas in the East and South China Seas allows the PLA to leverage precision missiles or strike aircraft based on its own territory for attacks, coordinated by hard-wired communications that cannot be jammed and interior lines of support that cannot be interdicted by U.S. forces without escalating a confrontation.5 These give the PLA firepower and sustainability advantages that, combined with China’s position as the aggressor, enable Beijing to drive the terms of an engagement and better anticipate how opponents will respond.

The Navy is addressing the PLA’s weapon range and capacity advantages by fielding refueling tankers that would extend the reach of carrier air wings, upgrading destroyers with improved radar and electromagnetic warfare systems, and developing unmanned surface vessels (USVs) that can carry missiles or decoy antiship missiles away from manned combatants.6 Unfortunately, these incremental efforts are unlikely to enable naval forces to fight effectively inside contested areas, which will reduce their ability to dissuade Chinese leaders from escalating a gray zone confrontation into a conflict.

Improvements to survivability and reach are fundamentally constrained by the size and power available per ship. For example, energy-based defensive weapons such as lasers have required the Navy to pursue a new, more costly ship design in the DDG(X) that will likely result in fewer surface combatants. Increasing a ship’s surface-to-air interceptors such as the SM-2 or Evolved Seasparrow Missile would necessarily reduce the number of vertical launch system cells available for offensive weapons.7 Extending the range of naval forces would require similar tradeoffs. Engineers could incrementally grow the range of existing aircraft or missiles by adding fuel at the expense of other payloads such as warheads. Larger jets and weapons could incorporate more fuel without sacrificing payload, but this would reduce the number of aircraft or weapons that could be carried per ship.8

Turning each Navy ship into a “Death Star” with formidable defenses and theater-wide reach would shrink the fleet by making each platform more expensive while playing into the PLA’s plans by making U.S. naval forces less flexible and more predictable. The Navy needs to break out of a symmetrical competition with the PLA over lethality and survivability by exploiting the “away team” advantages enjoyed by naval forces and evolving its force design around new metrics that account for attacking PLA strategy.

Attack China’s Strategy

The PLA’s ability to threaten large-scale systems warfare on short notice combined with insurgent-like operations by the People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia and China Coast Guard provide Chinese leaders options at multiple levels of escalation. Defeating this approach will require naval forces able to respond proportionally to gray zone aggression, undermine PLA commanders’ confidence in their plans for combat, and remain survivable in contested environments.

To pursue these objectives, Navy leaders will need to field a fleet that can execute a wider variety of effects per force package, sustain persistent presence overseas, and reduce enemy salvos to manageable sizes for each ship’s defenses without sacrificing offensive capacity or reach.9 A more distributed and disaggregated fleet would reflect these attributes. However, the Navy’s attempts to rebalance the force from dozens of large, manned, multimission ships to hundreds of smaller manned and unmanned platforms have fallen short because of requirements creep driving up the cost and complexity of smaller platforms, such as the guided-missile frigate, and congressional resistance to quickly fielding medium and large USVs.10

Although unsuccessful thus far, the Navy’s pursuit of a more disaggregated fleet is consistent with its distributed maritime operations (DMO) concept, DoD’s joint warfighting concept (JWC), and the U.S. Joint Staff’s joint all-domain command and control (JADC2) strategy. The JWC is classified, but unclassified reports and statements from DoD leaders emphasize its reliance on an approach called “expanded maneuver,” in which U.S. forces disaggregate for survivability or resilience and mass fires and other effects from long range. The JADC2 strategy is intended to support expanded maneuver by enabling data sharing and more dynamic recomposition of forces across all domains.11

The Navy’s failure to develop a more effective force for confronting great power insurgency is therefore not conceptual but instead the result of a lack of commitment and execution. Navy leaders could rebalance the fleet by embracing more fully the underlying principles of complexity, disaggregation, and sustainability in the JWC and DMO. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Mosaic Warfare concept and its overarching approach of decision-centric warfare reflect these objectives and could lead to a fleet better able to counter peer adversaries. Decision-centric warfare seeks to gain an optionality advantage over opponents, which includes a combination of a more disaggregated force design and a command-and-control (C2) process employing human command and machine control.12

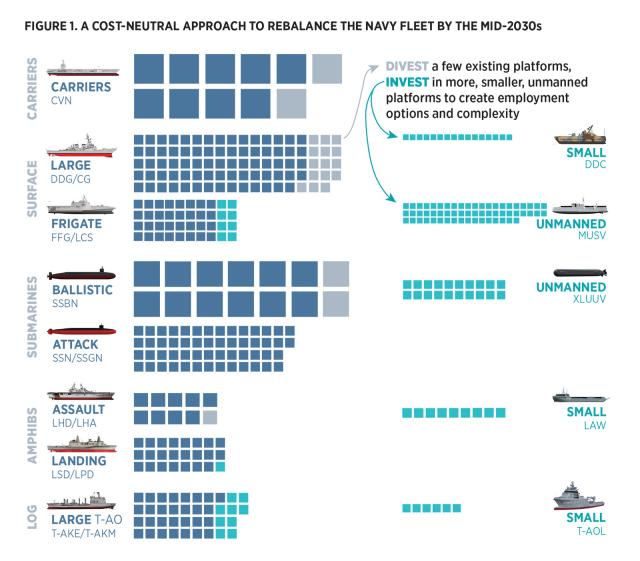

A disaggregated force design for the Navy (Figure 1) would replace some large multimission platforms with smaller, less multifunctional, and less expensive ships. Similarly, some amphibious transport docks would be replaced by light amphibious warships. Although a smaller portion of the fleet, large ships such as aircraft carriers would remain necessary for sustained offensive operations and to carry or support smaller platforms, which will likely lack the capacity or endurance to travel long distances into theater or conduct attacks while also defending themselves.

Disaggregated naval forces would provide commanders a wider array of options compared with today’s fleet. Smaller vessels can aggregate with each other for proportional responses to gray zone operations or combine with larger platforms at higher levels of escalation. And, most important, USVs or optionally manned vessels could operate independently in contested areas for high-risk missions.

To exploit the potential of a more disaggregated fleet, commanders would need decision support tools that help identify advantageous courses of action (COAs) and associated force packages. Today, these plans are developed by headquarters organizations such as maritime operations centers (MOCs), which rely largely on doctrine, history, and deliberation to formulate COAs. As a result, today’s COAs risk becoming relatively predictable to an opponent such as the PLA.

During a confrontation or conflict against China, communications with fleet headquarters likely will be degraded or lost, depriving naval commanders at sea of the benefit of the MOC’s planning staff. Automated decision-support tools such as those being developed in the Navy’s Project Convergence would help leaders execute mission command and expand the range of options a commander could consider, including unexpected COAs that an opponent is less likely to anticipate.13

The Navy’s posture also should change to take advantage of a rebalanced fleet design. With a larger number of smaller ships, the fleet’s deployed presence could consist primarily of forward-stationed LCSs, frigates, destroyers, and optionally unmanned USVs as a “deterrence force.” Larger force packages such as CSGs and amphibious ready groups, which are mainly based in the continental United States, would be free to operate throughout the Indo-Pacific region as a “maneuver force” that could spend more time on deployment preparing for high-end operations. This bimodal posture would improve the fleet’s sustainability by placing less-expensive vessels forward and keeping larger, more complex, costly platforms available in a higher state of warfighting readiness.14

Keep China’s Leaders on the Defensive

The Navy’s current path to address China is by pursuing dramatic improvements in ship lethality and survivability that do not change the underlying fleet architecture or operational approach. These efforts may help the Navy fight a Taiwan invasion more effectively but are unlikely to change Chinese leaders’ risk calculus. Deterring aggression through the risk of conventional denial is likely infeasible if the aggressor is China and the target Taiwan. Even if U.S. forces can stop the first attempt, China would still be only 90 miles away with 1.5 billion people and the world’s second-largest economy, allowing Beijing to try again, likely against little resistance.

Instead, U.S. Navy planning should accept more risk in the invasion scenario on the assumptions that such a conflict would be unlikely to be short, would entangle multiple U.S. allies and partners, and would require attacks on mainland China that could escalate to a nuclear conflict. The Navy should instead reduce risk in every other path China has to attain its objective of western Pacific hegemony, including maritime insurgency.15

The Navy could gain advantage across scenarios from maritime insurgency to invasion by establishing decision-making superiority. A rebalanced fleet would provide more force packaging options to commanders, allowing them to disaggregate, reaggregate, and recompose forces to increase the enemy’s uncertainty and adapt to the actions of Chinese military and paramilitary operations. Managing a more distributed naval force using human command and machine control would further expand the range of COAs available and allow leaders to choose options that maintain their decision space as a conflict progresses.

A naval force with greater adaptability, sustainability, and scalability would allow U.S. leaders to surprise Beijing and calibrate responses to Chinese hybrid or gray zone offensives. This would enable an approach to naval operations like that used by U.S. Cyber Command in its strategy of forward defense. By persistently engaging opposing operators and hackers inside their networks, U.S. cyber forces keep adversaries on the defensive, learn enemy tactics and capabilities, and create uncertainty for opposing leaders.16

Navy leaders should evolve the fleet and its C2 processes and enable it to persistently engage adversaries across the range of likely scenarios. The resulting naval force may sacrifice some capabilities in the unlikely worst-case scenario, but it will be better able to confront great powers across the full spectrum of threats they pose instead of mounting a goal-line defense against major power war and ceding the field against every other play.

1. Ronald O’Rourke, U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas: Background and Issues for Congress, Congressional Research Service, 26 January 2022.

2. Michael Mazaar, Katharina Ley Best, Burgess Laird, Eric V. Larson, Michael E. Linick, and Dan Madden, The U.S. Department of Defense’s Planning Process: Components and Challenges (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2019).

3. Robert Farley, “Could a ‘Cuban Missile Crisis’ Start Between the U.S. and China Over Taiwan?” 19fortyfive.com, 19 July 2021.

4. Jeff Engstrom, Systems Confrontation and System Destruction Warfare (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2018).

5. Ronald O’Rourke, China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress, Congressional Research Service, 8 March 2022.

6. Sam LaGrone, “Navy Releases Final MQ-25A Stingray RFP; General Atomics Bid Revealed,” USNI News, 10 October 2017; LaGrone, “Navy Unveils Next-Generation DDG(X) Warship Concept with Hypersonic Missiles, Lasers,” USNI News, 12 January 2022 and Ronald O’Rourke, Navy Large Unmanned Surface and Undersea Vehicles: Background and Issues for Congress, Congressional Research Service, 17 February 2022.

7. Bryan Clark and Timothy A. Walton, Taking Back the Seas: Transforming the U.S. Surface Fleet for Decision-Centric Warfare (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments [CSBA], 2020).

8. This effect is detailed in Mark Gunzinger and Bryan Clark, Sustaining America’s Precision Strike Advantage (Washington, DC: CSBA, 2015).

9. These metrics are also applied in Bryan Clark, Timothy A. Walton, and Seth Cropsey, American Sea Power at a Crossroads: A Plan to Restore the U.S. Navy’s Maritime Advantage (Washington, DC: Hudson Institute, 2020).

10. Megan Eckstein, “FY22 Shipbuilding Budget Could Do More to Pave the Way for U.S. Navy Fleet Transformation, Experts Say,” Defense News, 14 June 2021.

11. Christopher H. Popa et al., “Distributed Maritime Operations and Unmanned Systems Tactical Employment,” Naval Postgraduate School (June 2018), 7; Nishawn S. Smagh, “Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2),” Congressional Research Service, last updated 1 July 2021; David Vergun, “DOD Focuses on Aspirational Challenges in Future Warfighting, DoD News, 26 July 2021; and Chad Peltier, “Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing on China’s Military Power Projection and U.S. National Interests,” U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, 20 February 2020.

12. Bryan Clark, Dan Patt, and Harrison Schramm, Mosaic Warfare: Exploiting Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Systems to Implement Decision-Centric Operations (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2020) and Bryan Clark, Dan Patt, and Timothy A. Walton, Implementing Decision-Centric Warfare: Elevating Command and Control to Gain an Optionality Advantage (Washington, DC: Hudson Institute, 2021).

13. Mallory Shelbourne, “Navy’s ‘Project Overmatch’ Structure Aims to Accelerate Creating Naval Battle Network,” USNI News, 29 October 2020; also see Andrew Eversden, “A Weapon System ‘Raises Its Hand’ If Available under DARPA Program,” C4ISRNet, 16 June 2020; and Kimberly Underwood, “DARPA Offers Advanced Planning System to the Air Force,” AFCEA Signal, 1 June 2019.

14. For more details, see Bryan Clark et al., Restoring American Seapower: A New Fleet Architecture for the United States Navy (Washington, DC: CSBA, 2017).

15. Bryan Clark and Dan Patt, “The Realistic Path to Deterring China,” National Review Online, 7 December 2021.

16. David Vergun, “‘Persistent Engagement’ Strategy Paying Dividends, Cybercom General Says,” DoD News, 10 November 2021. This approach also is proposed in Clementine G. Starling, Tyson Wetzel, and Christian Trotti, Seizing the Advantage: A Vision for the Next U.S. National Defense Strategy (Washington, DC: Atlantic Council, 2021).