Just as nothing focuses the mind like an impending hanging, nothing says a country has sovereignty like hauling someone into court for crimes such as piracy in its territory. China conducts state-sponsored extortion and military intimidation operations against U.S. allies and partners while remaining just below the level of armed conflict.1 In essence, China is operating a maritime insurgency in the form of state-sponsored piracy.2 The Marine Corps has proposed a partial solution to this problem in the form of Marine littoral regiments (MLRs).

An MLR can be effective in a conflict only if it is in place before the shooting starts, but current MLR designs offer few incentives for allies and partners to invite MLRs in. Further, the present structure does nothing to offset a Chinese economic or diplomatic backlash to countries that welcome an MLR.3 Therefore, the Sea Services must redesign the MLR to become part of a triservice integrated maritime force (IMF). An IMF can assist allies and partners in regaining and maintaining governance of and sovereignty over their territorial waters and rights in their exclusive economic zones, in keeping with the triservice maritime strategy, Advantage at Sea.4 It will fulfill the four essential goals of the stand-in force concept and thus be more likely to be invited in during peacetime competition, capable of competing in gray zone operations, and more effective when combat begins.5

An IMF will function better than an MLR alone because it will possess improved capabilities and authorities. Better organic sensors and abilities will allow an IMF to execute a wider range of missions to support U.S. friends and national strategy. It can be developed rapidly and deployed using existing platforms with some refinements obtained through a research cycle comprising wargames, analysis, and fleet experiments.6 The inclusion of Coast Guard personnel and assets will confer authorities that will enhance the IMF’s ability to contribute to low-end and gray zone competition compared with an MLR.

MLRs at Present

Commandant of the Marine Corps General David H. Berger developed the MLR concept as a means to support the joint force maritime component commander (JFMCC) in establishing sea control with land forces holding critical littoral terrain inside an adversary’s weapons engagement zone.7 To return the Marine Corps to its traditional maritime role, the 2019 Commandant’s Planning Guidance directed the Marine Corps to consider: “In the context of force design, we need better answers to the question ‘What does the Navy need from the Marine Corps?’” Specifically, how can the Marine Corps support establishment of sea control using landward forces that seize or control critical littoral terrain?8Force Design 2030 instructs Headquarters Marine Corps to comprehensively restructure the service and, specifically, to construct a formation “purpose-built to support joint maritime campaigning, inherently capable of facilitating other joint operations.”9

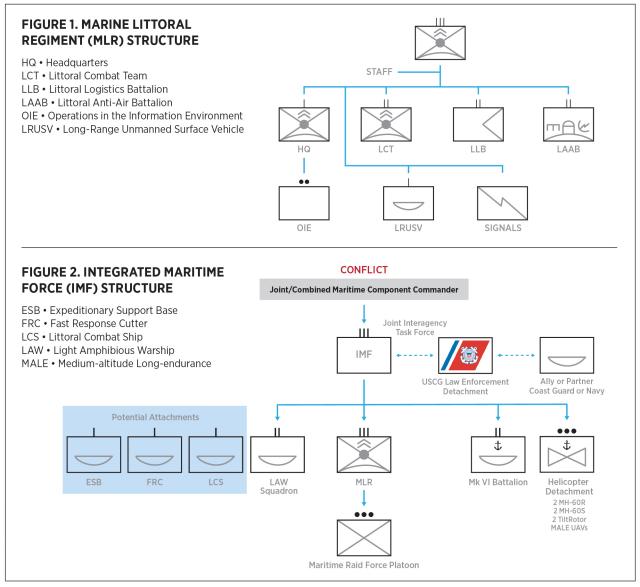

The MLR (see Figure 1) is designed for kinetic operations and deterrence and is conceived to maneuver and operate in critical terrain like that of the first island chain.10 Current designs for MLRs comprise a littoral combat team (LCT), a logistics battalion, and an antiair battalion. An LCT comprises a headquarters company, three infantry companies, and a medium missile battery. Infantry battalions provide shore-based security and can conduct offensive operations to seize and secure littoral terrain. The air-defense battalion provides what the name implies, while the logistics battalion supports all elements of the MLR. The missile battery will have shore-based antiship cruise missiles such as the Naval Strike Missile. MLRs will also include a long-range unmanned surface vehicle (LRUSV) platoon and a signals unit. Each MLR also could control a squadron of nine light amphibious warships (LAWs).11 The MLR can provide fires and other capabilities to the JFMCC to control that key terrain and the adjacent seas.12

The Integrated Maritime Force

Achieving the goals of the triservice maritime strategy requires incorporating Navy and Coast Guard assets with MLRs. This will give the joint force an integrated maritime force capable of challenging competitors during peacetime and gray zone operations while offering the joint force a more effective capability during armed conflict. Figure 2 illustrates the Navy and Coast Guard assets needed to enhance MLRs. These enhancements will enable each service to employ its core competencies and support allies and partners while providing critical organic sensors that enable full use of weapon systems.

In addition to the Marine Corps units already in the MLR, an IMF infantry battalion will need maritime raid force (MRF) platoons capable of taking down suspect vessels.13 Currently, MRFs deploy with Marine expeditionary units supported by Navy boats and helicopters.

MLRs should turn the antiship mission over to the Navy Expeditionary Combat Command. Navy fire controlmen and missile technicians can operate the IMF’s cruise missile systems, including coastal radars and other surveillance systems to enable coordinated fires, acting like the combat information center of a ship. The unmanned surface vessels should be replaced or augmented by long-endurance manned platforms like the decommissioned Mark VI patrol boats to enable boarding of suspect vessels and other maritime security operations.

A naval aviation detachment would greatly assist the IMF. An MH-60R would allow the IMF to see much farther, using the helicopter’s surface-search radar, sonar, electronic support measures, and other sensors, thus enabling its weapons to be used to the greatest effect at the longest range. An MH-60S would provide tactical medical evacuation, vertical lift for the MRF, and critical logistics support. MH-60S squadrons are integrating MQ-8C unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) as part of a Navy-wide manned-unmanned teaming effort that will bring additional capabilities to an IMF.14 Next-generation vertical-takeoff and landing UAVs would improve surveillance endurance and range while eliminating dependence on vulnerable airfields.15 The ashore aviation detachment can maintain its aircraft using small helicopter pads. Littoral combat ships could be attached to an IMF to provide maintenance support for rotary-wing aircraft. Expeditionary sea bases can offer additional aviation and boat support. Coast Guard cutters could be attached to support maritime security operations, with the IMF providing forward logistics.

Perhaps the most important element could be Coast Guard law enforcement detachments supporting a peacetime operational commander of a joint interagency task force (JIATF). Unlike the JIATF in U.S. Southern Command, which focuses on counternarcotics, the western Pacific JIATF would emphasize competing in the gray zone. In day-to-day contact with China in the South China Sea, the Coast Guard would lead the JIATF in helping local navies and coast guards maintain control of their territorial waters and exclusive economic zones.16 Navy helicopters and boats would provide operating platforms while the MRF provides security for boarding operations, and the Coast Guard ensures (with host-nation shipriders) the proper legal authorities are in operation—all under the protective overwatch of shore-based missile batteries and armed helicopters.17 In time, the JIATF will train local forces to execute protected governance and sovereignty missions themselves.

Improving Gray Zone Effectiveness

An integrated maritime force will offer allies and partners capabilities to address their most pressing and ongoing needs and the ability to protect and control their territorial waters and exclusive economic zones. The China Coast Guard and People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) gain effective control of places inside and outside the South China Sea and press China’s excessive claims into the territorial waters and economic exclusion zones of U.S. allies and partners.18 China’s coast guard makes possible militia harassment of local fishermen and seizure of critical geographic features, all of which in turn is supported by the implied threat of People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) military force.19 The presence of an MLR in the region by itself might deter the PLAN, but an MLR does little to deter the PAFMM or coast guard. On the other hand, an integrated force offers a broader range of capabilities and authorities to oppose China’s gray zone activities because an IMF puts the right personnel at the scene of action to support local allies and partners in a manner proportionate to the malign activities.

Unless it is augmented by the rest of the IMF, an MLR can offer little to no support in issues of sovereignty and governance. For this reason, many countries may be unwilling to host an MLR, making it less likely to be in position when a crisis starts. China’s counterintervention doctrine—commonly referred to as antiaccess/area-denial (A2AD)—is designed to make outside forces responding to a crisis fight to get into position. Thus, the best way to deter conflict is to have a presence in theater day-to-day.20 However, China’s counterintervention strategy includes elements for the competition phase of conflict, in which it employs a wide range of diplomatic, information, and economic levers alongside military ones against nations that host U.S. forces. A few community relations projects—repainting schools, building soccer fields, etc.—are insufficient to offset the economic pain China can inflict.

By having a broader set of capabilities, an IMF will be more effective in the competition phase and more welcome ahead of a crisis or conflict—and, thus, already present when the crisis arrives. An IMF will be an important contribution to enabling friends and allies to regain effective control of their fishing grounds and restore the livelihoods of their fishermen in a way an MLR alone cannot be. The mark of the IMF’s success in competition would be when revanchist China removes its maritime militias.

If necessary, the IMF will support a host nation in the arrest and prosecution of militias illegally operating in its waters or exclusive economic zone. The U.S. boats, ships, and helicopters will provide personnel at the scene of action and, if required, support the MRF’s boarding capability. The MLR element will provide overwatch for the maritime law enforcement elements, holding Chinese militia and other forces at risk. This would reduce or neutralize China’s strategy of gaining effective control by intimidation and grant the United States and its allies escalation dominance, crucial to winning the gray zone competition.

Improved Combat Effectiveness

In the event of open conflict, the IMF military commanding officer will become the operational commander in support of the JFMCC. Patrol boats, MH-60R helicopters, and UAVs will provide organic sensor support and augment antisurface fires from the missile batteries and LRUSVs. The helicopters and UAVs also will provide antisubmarine surveillance and prosecution, all under the protection of the antiair battalion.

These organic sensors and capabilities will be crucial to the success of MLR and IMF forces against a peer competitor that regularly practices severing connectivity between inside and outside forces while disabling the airfields that could offer support.21 While China will desire to neutralize shore-based antiship cruise-missile batteries by severing communications, the use of organic sensors and meshed networks could ensure the batteries and unmanned systems remain available to local commanders. Just as important as the weapon systems will be the deterrent value of U.S. military personnel, whose blood China may be reluctant to spill.

With existing platforms and formations, an IMF could be deployed as a JIATF within a year. Such an effort will quickly demonstrate to allies and partners the U.S. determination to support their sovereignty, gaining access to confront China ahead of a specific crisis. Testing and research (including wargames, analysis, and fleet experiments) will refine the concept.

The Commandant of the Marine Corps has correctly identified the need for the Marine Corps to evolve, but, alone, the MLR lacks the forces and capabilities required to respond to the full range of possibilities in confronting China or other revanchist powers. U.S. allies and partners need help to push back against Chinese encroachment, and the United States needs better access in case deterrence fails. An integrated maritime force improves the chances of both.

1. Hunter Stires, “The Maritime Counterinsurgency Project Begins,” and Geoffrey Till, “At War with the Lights Off,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 148, no. 7 (July 2022). See also, “Philippines Accuses Chinese Coast Guard of Firing Water Cannons on Its Supply Boats,” Reuters, 18 November 2021.

2. The depredations against sailors described in the cited articles certainly meet the definitions of piracy listed in Part VII, Article 101, of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, but in this case, they are state sponsored.

3. Brent Sadler, “Win the Contest for a Maritime Rules-Based Order,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 148, no. 7 (July 2022).

4. Secretary of the Navy, Advantage at Sea: Prevailing with Integrated All-Domain Naval Power (Department of the Navy, December 2020).

5. LtCol Gary Lehmann and Maj Greg Lewis, USMC (Ret.), “The Role of Stand-In Forces in Maritime COIN,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 148, no. 7 (July 2022). The four goals are: 1. Seek and support efforts that incentivize compliance with international law; 2. deter escalation while responding to harassment; 3. empower allies and partners to defend and exercise their sovereignty; and 4. in conflict, help defend allies against aggression while enabling the introduction and employment of additional forces.

6. Peter Perla, The Art of Wargaming (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press 1990), chapter 9.

7. Headquarters Marine Corps, Tentative Manual for Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (February 2021).

8. Gen David H. Berger, USMC, Commandant’s Planning Guidance (U.S. Marine Corps, March 2019).

9. Gen David H. Berger, USMC, Force Design 2030, U.S. Marine Corps (March 2020).

10. Headquarters Marine Corps, Tentative Manual; and Mallory Shelbourne, “Marine Corps to Stand Up First Marine Littoral Regiment in FY 2022,” USNI News, 20 January 2021.

11. David Axe, “Meet Your New Island-Hopping, Missile-Slinging U.S. Marine Corps,” Forbes, 14 May 2020; Todd South, “Marine Corps Looks at Building 3 New Pacific Regiments to Counter China,” Marine Corps Times, 3 February 2021; David Larter, “With U.S. Marines Seeking Unmanned Logistics to Fight China, Textron Sees Opportunity,” Defense News, 15 January 2020; and “Hawaii 1st to Receive New Amphibious Warships as Part of Marine Littoral Regiments,” Marine Corps Times, 23 February 2021.

12. Shawn Snow, “New Marine Littoral Regiment, Designed to Fight in Contested Maritime Environment, Coming to Hawaii,” Marine Corps Times, 14 May 2020.

13. Cpl Jered Stone, USMC, “Sustaining in Jordan: The MRF Takes to KASOTC to Brush up on Tactics Proficiency,” Marines.mil, 24 April 2018.

14. Megan Eckstein, “Navy Fielding MQ-8C Fire Scout to Operational Squadrons Ahead of Deployment Next Year,” USNI News, 5 October 2020.

15. Mallory Shelbourne, “Admiral: Next Navy Helos Will Be Mix of Manned, Unmanned,” USNI News, 1 April 2021; and “DARPA Seeks Leap-Ahead Capabilities for Vertical Takeoff and Landing X-Plane,” DARPA.gov, 7 September 2022.

16. James Holmes, “You Have to Be There,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 148, no. 6 (June 2022): 34.

17. “U.S., Federated States of Micronesia Sign Expanded Shiprider Agreement,” Coast Guard News, 13 October 2022.

18. Sadler, “Win the Contest.”

19. Hunter Stires, “Win Without Fighting,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 146, no. 6 (June 2020). See also Till, “At War with the Lights Off,” on China’s “cabbage strategy.”

20. Holmes, “You Have to Be There.”

21. Jeffrey Engstrom, Systems Confrontation and System Destruction Warfare: How the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Seeks to Wage Modern Warfare (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018).