The submarine, little more than an experiment before 1900, became a key instrument of U.S. sea power as the years passed. Its exploits came to the attention of the Commanders in Chief, and several of them spent time on board boats. Each President who made the extra effort to understand the men, mission, and capabilities of the Silent Service had a profound impact on U.S. submarine development.

By all accounts, 26 August 1905 was a terrible day for a boat ride; northeast winds and driving rain raised the seas in Oyster Bay, Long Island, forcing the passengers in a small boat to don foul weather clothing for their trip to the USS Plunger (SS-2). The Plunger’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Charles P. Nelson, was escorting President Teddy Roosevelt for the first presidential dive on board a U.S. submarine.

Roosevelt, ever a Navy man at heart, likely welcomed this intriguing distraction. He spent several hours in the Plunger as Nelson demonstrated machinery and maneuvers. The President used the boat’s rudimentary periscope and conning tower windows for a simulated torpedo run and experienced “angles and dangles,” an exercise that places the boat in steep up and down positions, showcasing her performance.

Roosevelt saw the professionalism of the Plunger’s crew. In recognition of the risks they bore and the technical proficiency required for submarine duty, he signed an executive order on 8 November 1905, authorizing submarine pay.1

To some, Roosevelt’s trip seemed to be a stunt, but the Washington Times reported: “Great results are expected to follow from the President’s trip in the Plunger. Every naval authority in the world, attention having been attracted by the President’s experience, will be looking into the construction and usefulness of the Plunger.”2

Forty-one years would pass before another sitting U.S. president made a submarine voyage. On 21 November 1946, Harry S. Truman spent a day at sea on board the former German U-2513, acquired as a war prize by the U.S. Navy. She and her sister, the U-3008, were assigned to Submarine Squadron 4 in Key West for evaluation of their advanced snorkel systems; the Type XXI snorkel was on a retractable mast housed in the boat’s conning tower. In addition, these boats pioneered streamlined design and had a high degree of automation.

Truman and several key staffers submerged in the U-2513, witnessing firsthand the tactical advantages of the snorkel over battery power. Later, the U-2513 dove to 440 feet. Reserve Navy Captain Clark Clifford, Truman’s naval aide, noted: “It was interesting to . . . see the efficiency with which the men handled their various assignments. I think the Navy personnel involved were delighted to have that opportunity of demonstrating their competence to the President.”3 The trip unquestionably emphasized the tactical advantages of the late World War II German submarine technology.

Truman made ten more trips to Key West during his presidency and spent considerable time on the submarine base. He visited the U-2513 again on 5 December 1947 and later inspected the USS Requin (SS-481) pierside on 28 February 1948. On the Requin visit, Truman was accompanied by his naval aide, Captain Robert Dennision (former commander of the USS Cuttlefish [SS-171] ). Truman’s last visit with the submarine force was near the end of his second term, to give the keynote address at the keel laying of the USS Nautilus (SSN-571).

The eight years of the Eisenhower administration saw the launch of 18 nuclear-powered boats. Nuclear technology enabled the Silent Service to make tremendous leaps forward. In the late 1950s, U.S. nuclear-powered submarines crossed under and surfaced at the North Pole; circumnavigated the globe submerged; and conducted the first Polaris strategic deterrent patrol.

Eisenhower’s naval aide, noted World War II submarine veteran Captain Edward “Ned” Beach, led the effort for First Lady Mamie Eisenhower to christen the Nautilus in 1954. The President then spent time underway submerged in the USS Seawolf (SSN-575) on 26 September 1957. Before his short cruise ended, he addressed the crew:

I suppose you know this is the first time I’ve been aboard an atomic reactor submarine. Everything was of interest to me—all of the gadgets and the machines—but more interesting to me was to see the United States Navy at work. I’m proud of every man aboard ship.4

Eisenhower later visited the USS Patrick Henry (SSBN-599) off Newport on 25 July 1960. After a brief belowdecks tour, he boarded the presidential yacht Barbara Anne and observed the surfaced firing of two dummy sabots simulating Polaris missile launches.5

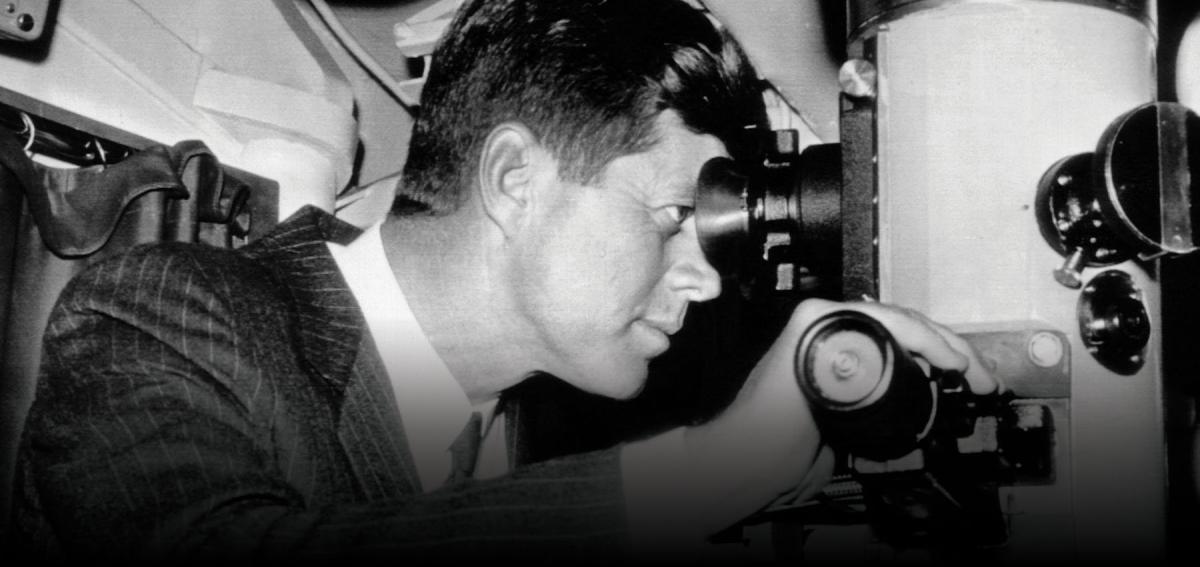

President John F. Kennedy’s World War II naval service undoubtedly gave him some understanding of submarine operations, but his association with the Silent Service was brief. As President, he visited the USS Thomas A. Edison (SSBN-610) as part of a fleet visit on 13–14 April 1962. He made a short surface transit in Hampton Roads before departing to tour additional ships. In November 1962, Kennedy visited the USS Chopper (SS-342) in Key West. The Chopper had recently returned from quarantine duty off Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Kennedy’s final contact with the submarine force was in November 1963, witnessing the firing of a Polaris missile by the USS Andrew Jackson (SSBN-619) from on board the USS Observation Island (EAG-154).

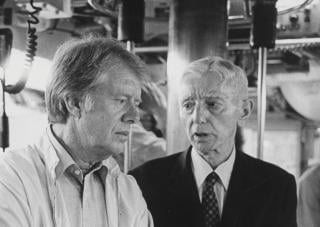

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter joined his former mentor Admiral Hyman Rickover on board the USS Los Angeles (SSN-688). During his active-duty Navy career, Carter had served in the USS Pomfret (SS-391) and Barracuda (SSK-1), and he was slated to report to the USS Seawolf (SSN-575) when his father’s death prompted him to resign his commission. He wouldn’t see the interior of a submarine for another 24 years, but what a submarine it was!

Shortly into his presidency, Carter and First Lady Rosalind Carter embarked the Los Angeles in Port Canaveral, Florida, for an overnight familiarization. The Los Angeles was the newest boat in the fleet and the lead vessel of the 688 class.

Carter was impressed with the Los Angeles and wrote to the boat’s captain thanking him for the “cruise on what is very likely the finest ship in the world. I was proud of your performance, which strengthened my confidence in the Submarine Force.”6 The trip was an opportunity for Rickover to showcase the Navy’s achievements in submarine design. It must have worked, as the Los Angeles- and Ohio-class submarines remained in the Carter defense budget while other services saw cuts to new programs.

Shortly after the commissioning of the USS Jimmy Carter (SSN-23), the Carters embarked for an overnight familiarization. To date, Carter remains the only chief executive “qualified in submarines” and entitled to wear the coveted Dolphins.

In November 1980, former President Richard Nixon was welcomed on board the USS Cincinnati (SSN-693) for an overnight trip. Nixon received a thorough familiarization on submarine operations, including steering the boat with the helmsman and controlling speed as throttleman. The crew provided all the usual submarine entertainment: angles and dangles, high-speed maneuvers, and the firing of simulated torpedoes.

The President held a lively and informative Q&A session in the crew’s mess, where he shared his thoughts on the opening of relations with the People’s Republic of China, the 1980 U.S. national elections, the economy, and the Iranian hostage crisis.7

Nixon knew the importance of the U.S. nuclear submarine fleet. In 1972, the USS Guardfish (SSN-612) trailed a Soviet Echo-class cruise-missile submarine for 28 days during a critical period in the Paris Peace Talks ending the Vietnam War. Nixon received daily updates on the Guardfish’s status and the proximity of Soviet submarines to U.S. vessels off Vietnam.

Although he never stepped on board a submarine as President, Lieutenant (j.g.) George H. W. Bush spent time on board the USS Finback (SS-230), which rescued the future President after his TBF Avenger torpedo bomber was shot down over Chichi Jima in September 1944.

Ronald Reagan also never embarked a submarine during his presidency, but while filming Hellcats of the Navy, he was topside on the USS Besugo (SS-321) practicing his lines, when, according to Hollywood legend, the crew thought his commands were real. The sailors responded to Reagan’s engine orders before the future President was isolated from the intercom and the command “All Stop” was passed.

Presidential interest in the Silent Service helped advance submarine technology; supported U.S. diplomacy and global vigilance; and improved pay for the Navy’s submariners.

1. Executive Order 366-B was codified by Navy Department General Order 9 on 9 November 1905.

2. “President Goes Far Underwater,” Washington Times, 26 August 1905. Navy Source Online, Submarine Photo Gallery.

3. Jerry N. Hess Oral History interview with Clark M. Clifford, Assistant to White House Naval Aide, 1945–46, Special Counsel to the President, 1946–50 (Washington, DC: 14 February 1973), 417–19.

4. “Eisenhower Takes First Dive in Atomic Submarine,” The New York Times, 27 September 1957.

5. “President Eisenhower Arrives on USS Patrick Henry in Newport for Inspection,” YouTube.

6. Naval History and Heritage Command: Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships; “USS Los Angeles IV (SSN-688) 1976–2011.”

7. Anecdotal information gathered from oral interviews with USS Cincinnati crew members EMCM/SS Luther Clark, ETC/SS E. Stewart Crick, and EMC/SS Michael Pajewski, 14–15 June 2019.