The U.S. Marine Corps’ 2021 Force Design Update and Commandant of the Marine Corps General David H. Berger’s Military Review article, “Preparing for the Future: Marine Corps Support to Joint Operations in Contested Littorals,” orients the Marine Corps toward a role in maritime reconnaissance and counterreconnaissance for great power competition.1 The Commandant describes the utility of the Marine Corps in these missions as follows: “A light, self-reliant, highly mobile naval expeditionary force postured forward in littoral areas within the adversary’s WEZ [weapons engagement zone] would provide naval and joint force commanders the ability to identify and track high-value targets.”2

To maximize effectiveness, this force must be capable of operating across the competition continuum, including a Westphalian (i.e., conventional) warfare scenario.3 Furthermore, the maritime reconnaissance and counterreconnaissance missions must span multiple domains, such as physical areas, the information environment, and the electromagnetic spectrum.4 This will enable success given the current character of war, which necessitates military actions in multiple domains. The end state is a force that persists “within a peer adversary’s weapons engagement zone to sense and make sense of what is happening at any point on the competition continuum.”5

Marine Corps intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) formations will have a prominent role supporting the stand-in maritime reconnaissance and counterreconnaissance missions, as they enable intelligence and counterintelligence. To succeed across the competition continuum in a multidomain maritime reconnaissance and counterreconnaissance mission, the Marine Corps must persistently forward employ ISR formations during the steady state.6

Adapting to the Current Operating Environment

At present, Marine Corps ISR employment is largely reactive, as ISR assets are postured to respond when a crisis occurs. However, given the current character of warfare, the state-on-state armed conflict military leaders envision likely will never occur.Meanwhile, the U.S. naval force cedes the advantage to its adversaries as they pursue malign competition during the steady state.7 To provide the best opportunity for success in this operating environment, the Marine Corps must always be collecting intelligence and countering adversary collection through persistent forward employment. Persistent forward employed ISR adapts to the most common operating environment of gray-zone steady-state competition, while still being capable of high-end state-on-state warfare.

Persistent forward employment means ISR formations—whether they be multidiscipline teams, unmanned systems, or a coordinated network of both with multidomain sensors—are directly employed to collect or counter intelligence collection at all periods across the competition continuum.8 It includes continual overt, low-visibility, and clandestine intelligence and counterintelligence operations oriented on key maritime objectives. Integration with the larger intelligence community and other government agencies is necessary to maximize effectiveness and unity of effort, by leveraging assets, coordination, and support not otherwise available.

Persistent forward ISR employment during the steady state will be enhanced by changes to deployments, command relationships, and authorities. For example, Marine expeditionary units (MEUs) historically employ ISR assets in a reactionary method for crisis response in support of MEU operations. While the MEU can be a capable platform, it cannot maximize reconnaissance and counterreconnaissance missions because it must prioritize competing missions based on geographic combatant command tasking.9 One solution is to deploy Marine Corps ISR formations to support geographic maritime component commands with the mobility to move around the area of responsibility.

A Historical Perspective

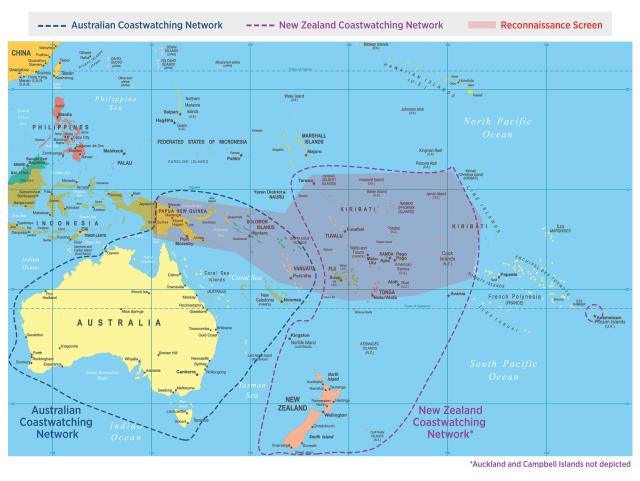

The Coastwatchers are a valuable historical example for multidomain intelligence operations in support of naval operations.10 The Coastwatchers were intelligence organizations controlled by the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) and the New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy (later the Royal New Zealand Navy) during the interwar years and World War II.11 Although Australia and New Zealand each controlled its own network, the systems were interlocked as a part of the Allies’ naval reconnaissance screen.12 The reconnaissance screen was spread across the Pacific islands north of Australia and New Zealand. The Coastwatchers provided intelligence of the air, sea, and land domains through observation posts, human intelligence, and teleradio communication stations.13 Admiral William Halsey Jr., who commanded naval forces during the Solomon Islands campaign, summarizes the Coastwatchers’ effectiveness: “The Coastwatchers saved Guadalcanal, and Guadalcanal saved the South Pacific.”14 The Coastwatchers were an indispensable part of the Allies’ success in the Pacific theater.

The early establishment of the Coastwatchers reconnaissance effort during the interwar years enabled their subsequent success. The Australian Coastwatchers began in 1919, and the New Zealand Coastwatching system began in 1929.15 Both systems provided maritime intelligence collection until war began in 1939, at which point they shifted their focus to defeating the Axis powers. In a 1961 Proceedings article, RAN Commander Eric Feldt explains the value of a proactive intelligence effort:

By September 1939, the Coastwatchers were eight hundred strong, the great majority of them, of course, on the Australian mainland. In Australia’s island screen, where Ferdinand [the name of the Coastwatching operation under the RAN] was eventually to operate, the system was still very thin and spotty, but at least a nucleus existed, and funds were available. Upon the outbreak of war . . . the Navy directed the organization, such as it was, to commence functioning.16

The Coastwatchers realized the benefit of proactive establishment of their intelligence organization. Proactive maritime reconnaissance and counterreconnaissance through persistent forward employment in the steady state is even more important in the modern era because of the increasingly dynamic and complex security environment.

Competing against the Pacing Threat

Persistently forward employing Marine Corps ISR during the steady state enables the naval force to better compete against the People’s Republic of China (PRC), a current focus of the Department of Defense and the pacing threat. China seeks dominance within the second island chain and influence throughout the strategic island chains of the Indo-Pacific.17 Through malign gray zone activity during the steady state, China pursues this strategic maritime objective, seeking to subtly intervene “in a situation long before armed conflict arrives.”18 The PRC’s maritime militia, fishing fleet, navy (the world’s largest), coast guard, and military occupation of atolls outside its territorial waters provide means to accomplish its maritime objectives across the competition continuum.19

Persistent forward Marine Corps ISR employment will help the naval services compete against the Chinese gray-zone strategy and enhance U.S. capability to respond during hostilities. Persistent forward employed ISR equates to presence and knowledge of key maritime terrain in the Indo-Pacific. For example, ISR along the island chains can contribute to a reconnaissance screen of PRC maritime activity, similar to the function of the Coastwatchers. Persistent forward employed ISR also increases the capability of the Marine Corps stand-in force inside the PRC WEZ by maintaining continuous intelligence and counterintelligence that does not rely on penetrating a WEZ during periods of increased hostility.20

The Advantage of Time

Early and continuous ISR employment gains U.S. naval forces the critical element of time, in which adversaries have a sizable advantage.21 The majority of friction points—locations in which crises are more likely to occur—are geographically closer to adversary centers of power than to the United States. Some include the South China Sea and China, the first island chain and China, the Strait of Hormuz and Iran, and the Northern Sea Route and Russia.22 The proximity difference puts the United States at a disadvantage because of the increased time it will take to mass combat power at a decisive point. An example of this disadvantage is the 2014 annexation of Crimea. Although the United States and its allies did not respond with a significant military counteraction during the annexation, Russia did demonstrate the advantage of proximity in the information environment and physical domains by gaining control of the adjacent peninsula and its warm water port of Sevastopol with little military resistance.23

The Marine Corps becomes reactive and loses critical tempo during a crisis when it waits until the steady state ends for the deliberate employment of ISR. Persistent forward employed ISR during the steady state helps mitigate this time disadvantage for forces maneuvering to key maritime objectives by contributing to a faster observe, orient, decide, and act (OODA) loop. This employment serves as “the Stand-in force to dominate the information environment, sense and make sense of the situation, and win the recon vs. counter-recon competition.”24 Presence and continuous steady-state intelligence collection produces a faster maritime intelligence cycle, while disrupting competitors’ OODA loop through counterreconnaissance.

Successful intelligence and counterintelligence must be built on a foundation established in the steady state because they provide a baseline of intelligence and the opportunity to degrade the adversary’s baseline. Army Lieutenant Colonel Stephan Pikner describes disrupting baselines during the steady state, “Persistent competition below the threshold of armed conflict should include deliberate efforts to monitor, mask, and simulate the full spectrum of friendly land force signatures.”25 Persistent forward employed ISR provides that opportunity to shape during the steady state, through maritime reconnaissance and counterreconnaissance. These operations can affect competitors’ intelligence baselines, which buys time throughout the competition continuum.

Special Reconnaissance and Operational Preparation of the Environment

A prominent counterargument to persistently forward employed Marine Corps ISR during the steady state is the existing employment of special operations units to conduct special reconnaissance (SR) and operational preparation of the environment (OPE). SR is “reconnaissance and surveillance actions conducted as a special operation in hostile, denied, or diplomatically and/or politically sensitive environments to collect or verify information of strategic or operational significance, employing military capabilities not normally found in conventional forces.”26 OPE is “the conduct of activities in likely or potential operational areas to set conditions for mission execution . . . OPE activities may include, but are not limited to, active and passive observation, area and network familiarization, site surveys, and mapping the information environment.”27 Some potential activities by persistently forward employed ISR formations can be categorized as OPE.28

Persistent forward employed ISR during the steady state will be enhanced by an SR and OPE capability within the Marine Corps that must be grown to maximize effectiveness. Special operations units that conduct SR and OPE already possess the equipment, training, and organization to do so. The capabilities exist within Marine Corps units, but additional technology, training, and authorities are required to make them comparable to special operations forces.29 While special operations forces are often the units of choice for SR and OPE, they have other competing mission sets, and they do not directly answer the naval service’s intelligence and shaping requirements unless a supporting relationship is established.30 Compounding this issue, SR and OPE mission sets span many competing requirements for a special operations force constrained by high demand.31 For the naval service, these factors cause unanswered intelligence requirements and a reduced capability to shape the operational environment.

To maximize persistently forward employed ISR, the Marine Corps will need to add SR and OPE capability through additional training and equipment. Persistently forward employed ISR units are not meant to create friction with the special operations community, but rather to integrate with them in the larger maritime intelligence/counterintelligence effort. Integrating persistently forward employed ISR units into theater special operation commands’ efforts will benefit the joint force in the pursuit of maritime objectives. The expansion of SR and OPE capability, one of persistently forward employed units, will require additional investment. A return on this investment is an ISR capability for the naval service that can actively compete deep in adversary areas during the steady state.

1. Gen David H. Berger, USMC, “Preparing for the Future: Marine Corps Support to Joint Operations in Contested Littorals,” Military Review (March-April 2021): 1; Gen David H. Berger, USMC, Force Design 2030 Annual Update (Washington, DC: Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, April 2021), 8–9.

2. Berger, “Preparing for the Future,” 3–4.

3. Sean McFate, The New Rules of War (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2019), 30-33; For a description of the competition continuum, Department of Defense, Competition Continuum, Joint Doctrine Note 1-19 (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 3 June 2019), 2–11.

4. Gen David H. Berger, USMC, Commandant’s Planning Guidance: 38th Commandant of the Marine Corps (Washington, DC: Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, July 2019), 12; Department of Defense, Joint Publication 3-0, Joint Operations (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Defense, October 22, 2018), IV-1–IV-2.

5. Berger, Force Design 2030 Annual Update, 8.

6. Steady state as used here is the most common period across the competition continuum where gray zone activity persists; there is an absence of major armed conflict, crisis response, or contingency. During the steady state, the components of national power shape conditions to compel the adversary to do our will, thereby avoiding the need for armed conflict or entering armed conflict under more favorable conditions. Jason M. Frazee, Brock Jones, and Scott D. McDonald, “Phase Zero,” 133; Headquarters U.S. Air Force, “Steady-State Operations,” in Basic Doctrine, vol. 1 (Maxwell Air Force Base, AL: Curtis E. Lemay Center for Doctrine Development and Education, 27 February 2015), 46.

7. Kenneth J. Braithwaite, Advantage at Sea: Prevailing with Integrated All-Domain Naval Power (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, December 2020), 3–5.

8. Sean Barnes and Ladd W. Shepard, “Manned and Unmanned Teaming: The Future of Marine Corps Reconnaissance Units,” Marine Corps Gazette 102, no. 5 (May 2018): 44–49.

9. Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps, Amphibious Ready Group and Marine Expeditionary Unit Overview, 2–6.

10. Justin Haynes, “Human Intelligence as a Deep Sensor in Multi-Domain Operations: Australia’s World War II Coastwatchers,” Military Intelligence Professional Bulletin 45, no. 3 (July-September 2019): 33-–38.

11. David Oswald William Hall, The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939-1945: Coastwatchers, Episodes and Studies vol. 2 (Wellington, NZ: War History Branch of the Department of Internal Affairs, 1951), 3; Department of Veterans’ Affairs, “The Coastwatchers 1941–1945,” DVA ANZAC Portal, last modified 30 April 2020.

12. Eric A. Feldt, The Coastwatchers (Coppell, TX: The War Vault, 2019), 12; Hall, The Official History of New Zealand, 4.

13. Peter Djokovic, “The Coastwatchers and Ferdinand the Bull,” Semaphore 4 (2014), 1-2; Hall, The Official History of New Zealand, 4–5; Haynes, 34.

14.Djokovic, 2.

15. Feldt, The Coastwatchers, 8; Hall, The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939-1945, 3.

16.Eric A. Feldt, “Coastwatching in World War II,” Proceedings 87, no. 9 (September 1961): 72.

17. Chelsea Bomping and Joshua Espena, “The Taiwan Frontier and the Chinese Dominance for the Second Island Chain,” Australia Institute of International Affairs, 13 August 2020.

18. Frazee et al., “Phase Zero,” 126.

19. Caitlin Campbell, China’s Military: The People’s Liberation Army (PLA), CRS Report for Congress R46808 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 4 June 2021), 17–18, 29–33.

20. Berger, Commandant’s Planning Guidance, 5.

21. Billy Fabian, “Overcoming the Tyranny of Time: The Role of U.S. Forward Posture in Deterrence and Defense,” Center for New American Security, 21 September 2020).

22. Olivia Garard, “Geopolitical Gerrymandering and the Importance of Key Maritime Terrain,” War on the Rocks, 3 October 2018).

23. U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command G-2 ACE Threats Integrations, Threat Tactics Report Russia, version 1.1 (Fort Eustis, VA: Training and Doctrine Command, October 2015), 20–34.

24. Berger, Force Design 2030 Annual Update, 8.

25. Stephan Pikner, “Leveraging Multi-Domain Military Deception to Expose the Enemy in 2035,” Military Review (March–April 2021): 86.

26. Department of Defense, Joint Publication 3-05, Special Operations (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 22 September 2020), GL-10.

27. Department of Defense, Special Operations, IV-7–IV-8.

28. For additional context on OPE, Joshua Kuyers, ““Operational Preparation of the Environment”: “Intelligence Activity” or “Covert Action” by Any Other Name,” American University National Security Law Brief 4, no. 1 (2013): 23–29, 31, 37–40.

29. Ian C. Fletcher, “Advance Force Operations: The Middleweight Force’s Essential Role in Joint Operations,” master’s thesis, Marine Corps University, 2013, 22–26, 33–34, 38–39.

30. Department of Defense, Special Operations, II-4, III-1–III-23.

31. David Barno and Nora Benashel, “How to Fix U.S. Special Operations Forces,” War on the Rocks, 25 October 2020); McFate, The New Rules of War, 37–38, 41.