On 12 November 1940, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Harold K. “Betty” Stark, undertook to lay out U.S. options in the event of war against Germany, Japan, or both. In a way that is nearly unimaginable today, he wrote it himself, at home, without any staff support or involvement. It took him eighteen hours, working straight through, to complete his analysis. He reviewed several possible scenarios and plans, lettering them from “A” through “D,” and ultimately recommended Plan “D.” At that time, the U.S. Navy’s phonetic alphabet for “D” was “dog”: hence it became known as the “Plan Dog Memorandum.”

To appreciate Admiral Stark’s brilliance, it is important to understand something of the context in which he wrote his memorandum. During 1940, after continued German, Italian, and Japanese campaigns of conquest, U.S. leaders came to realize that the scenarios underlying the old “color-coded” war plans—that the United States would fight a war against a single enemy one-on-one—were no longer realistic. The United States was increasingly likely to face war against multiple enemies across the globe. In which case, the country would need allies—which, by late 1940, meant the British Empire.

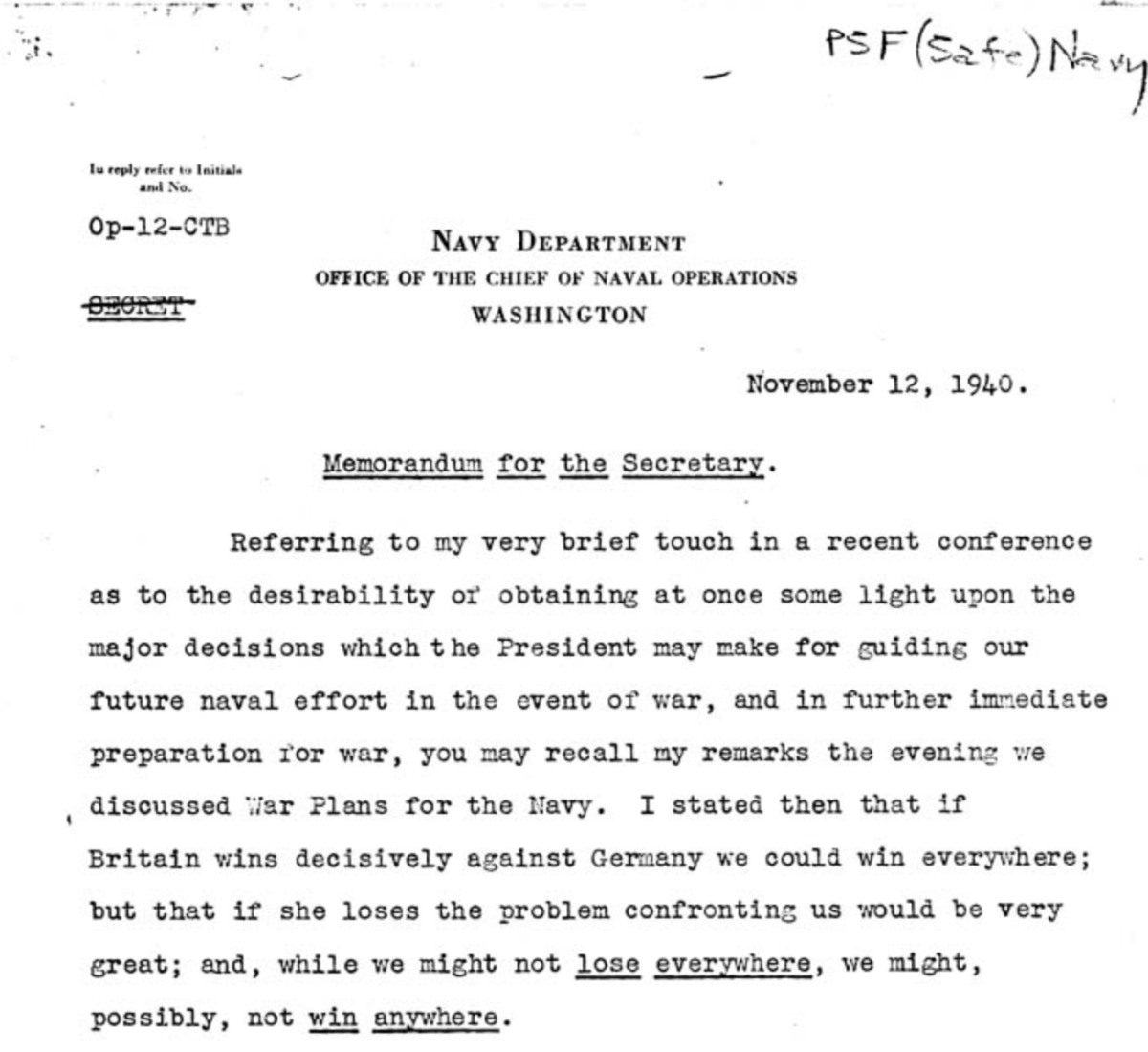

(Naval History and Heritage Command)

By November of that year, France had fallen, and Britain stood alone against Nazi Germany and its Italian allies. The German bombing campaign—the Blitz—against Britain had begun. Recognizing the consequences of a British defeat, President Franklin Roosevelt had been gradually increasing U.S. support to the United Kingdom, first through the “cash and carry” policy in September 1939, and then through the “destroyers for bases” deal in September 1940 (Lend-Lease would follow in December 1940). In Asia, meanwhile, Japan’s invasion of China continued, and in September they occupied the northern part of French Indo-China.

However, Roosevelt was constrained by public opinion, which strongly opposed U.S. involvement in another major foreign war. Stark’s memorandum, therefore, came at a critical time—before the United States was formally at war, but as war was looking more and more likely. It was by no means clear what course the United States should or would follow.

Admiral Stark laid out the essence of the grand strategic problem facing the United States, and he concisely crafted the best courses of action. He did so with a deep understanding of the U.S. military, the nation’s political culture, and the mood of its people. Note the importance he rightly attached to public opinion and public expectations.

Similar to Stark, we must ask (and answer) the hard questions. Should the United States stand and oppose Chinese aggression? If it does not, what will be the impact on U.S. and global security and prosperity? If the United States does oppose Chinese hegemony, what will be the likelihood of war? What would such a war look like and how best to prepare for it? What role would sea power take in such a conflict?

To this nation’s—and the world’s—great benefit, CNO Stark had the training, education, and intellect to pen this memo, at home, on his own, in a day. That is worth remembering. Doubtless each reader will come away with different conclusions from the Dog Memo; yet every reader’s understanding of strategy, national security, and the naval profession will be enlightened in the reading.