Moral philosophy is complicated. Some philosophers insist the only consideration that matters when judging the morality of an action is the principle that guides that action. The outcomes of our choices, they say, are morally unimportant. Others counter that it is absurd to disregard consequences. If an act brings more pleasure into the world than pain, then surely that is the right thing to do. And then there are those who find both approaches overly formulaic. If you are a good person, they contend, you will make good choices.

One result of this complexity is that moral theory tends to be an activity for moral theorists and of little value to the rest of us. But seven questions, taken together and in order, can narrow the gap between theory and practice and bring discipline to the enterprise of moral reasoning.

#1: Is this a routine moral choice or one that warrants deliberate moral reflection?

You smile and offer pleasant “good mornings” to your shipmates in the passageway, even though you’re feeling cranky after your 0200–0700 watch. When you swing by your stateroom to splash water on your face before the department head meeting, you don’t rifle through your roommate’s wallet, even though he’s still at breakfast and probably wouldn’t notice the missing twenty. When the executive officer asks a tough question at the meeting, you tell her the truth, even though you know the answer will disappoint her.

Every day, we make countless moral choices like these without even perceiving them as moral choices. We treat others with courtesy. We respect private property. We tell the truth. And we do all these things without stopping to consider what Immanuel Kant or Aristotle would advise. These are routine moral choices. As children, most of us learned what good (and bad) decisions look like in situations like these. We “put in the reps,” made a few mistakes along the way, and, ultimately, developed muscle memory for doing the right thing.

Sometimes, however, our routines are interrupted by situations our moral habits cannot reliably address. At that point, we need to slow down and engage in deliberate moral reflection.

Distinguishing routine moral choices from those requiring intentional deliberation is a critical competency for ethical living. It’s also hard. The border marking off these two domains is indistinct and poorly signposted. Furthermore, environmental factors such as stress, fear, or social pressure can obscure essential features of the moral terrain and cloud our judgment.1

Three alerts can help us recognize that it is time to set aside our moral standard operating procedures and proceed to Question 2. The first is simply the novelty of the situation. “Huh, that’s new,” is a phrase that should prompt us to pause. The second alert is a recognition that a problem involves multiple and conflicting moral obligations. For example, you can be honest and rat out a shipmate, or you can be loyal to your shipmate and lie to the skipper. But you can’t be both. The third and most reliable signal that the moral choice you’re confronting is not routine is your gut. Rather than knowing the answer to Question 1, you feel it.

In a talk at the Naval Academy, philosopher Rushworth Kidder described this feeling as “crossing the moral thermocline.” A thermocline is a boundary between layers of warmer and colder water. When a diver descends in a column of water, the temperature remains relatively constant until she hits the thermocline and immediately wishes she had worn a thicker wetsuit. The diver can’t see the thermocline—water is just as transparent below the thermocline as above—she feels it.

Kidder’s moral thermocline acts similarly. Before our intellect grasps that we no longer are in the realm of routine moral choice, we feel it. The hair on the back of our necks stands up. Our stomachs churn. Our throats tighten. Our moral intuition is telling us it is time to pay attention and turn to Question 2.

#2: How much time do I have?

Time is a moral factor.

In summer 1988, the USS Dubuque (LPD-8) was in the South China Sea en route to mine countermeasures operations in the Persian Gulf when she encountered a vessel containing refugees in apparent distress. Behind schedule and feeling pressed for time, the captain ordered his executive officer to motor out to the refugee vessel and conduct a hasty visual inspection—but not to board the craft. Doing so would increase risk and take time.

Based on information hurriedly gathered by the executive officer and the marginally capable translator who accompanied him, the captain determined there were about 60 Vietnamese refugees on board. They had completed about half their journey from Vietnam to the Philippines in just over seven days—excellent progress for a boat powered by only a small sail. He judged the craft seaworthy and ordered it provisioned for another seven days at sea. The Dubuque then resumed her transit to the Gulf at full speed.

The refugees’ situation was far more desperate than the hurried inspection revealed. The vessel was not a sailboat. The makeshift sail was a desperate measure taken when the engine had failed days before. The refugees had been at sea for 17 days, not 7. There were 90 refugees on board, not 60, and 20 had already perished.

Had the inspection team taken even another ten minutes, the executive officer would have discovered most of these facts, and the captain—an officer with a sterling record and reputation—would have made lifesaving decisions. Instead, the refugees remained adrift for another 19 days before Filipino fishermen rescued them. With insufficient provisions, 30 more died, and the survivors resorted to cannibalism.2

We often make poor moral choices because we feel time pressing in. Time changes our decision-making strategies. We limit our search for information, consider fewer alternatives, give greater weight to information that confirms hasty conclusions, and discount contradictory data.3 Rather than engaging in deliberate reasoning, we switch to quick, intuitive thinking.4

Sometimes the time crunch is real. Often, however, it is not as bad as we think. If, before acting, we ask ourselves Question 2, we are less likely to make hasty moral judgments based on a false sense of urgency. If we have two seconds to make a decision, we should make our decision in two seconds. If we have two hours, two days, or two weeks, we should take that time. The decisions we make on the cold side of the moral thermocline are too consequential to rush unnecessarily. Sometimes they are life-changing, as they were with the Dubuque.

#3: Am I facing a moral dilemma or a test of integrity?

It is useful to distinguish between moral dilemmas and tests of integrity, because this distinction determines which of two paths moral reasoning should take.5

Moral dilemmas are situations in which right and wrong are unclear. When facing a moral dilemma, skip Question 4. For tests of integrity, we already know the right and wrong thing to do but, for various reasons, find it difficult to do what we know is right. If the answer to Question 3 is “test of integrity,” proceed to Question 4.

#4: Do I have the character and judgment to do the right thing?

When confronted with a test of integrity, moral reasoning is simple: Ask yourself Question 4, answer it with an enthusiastic, “Yes, I do have the character and judgment to do the right thing,” and then do the right thing.

Integrity tests are simple. That does not mean they are easy. We have all failed them. More failures likely lie in our futures. Indeed, it seems to be part of the human condition that knowing the right thing to do is only a condition for doing the right thing. It isn’t sufficient. In short, moral temptation is real.

While most of us can boast of a long ledger of integrity tests we’ve passed, humility is warranted. How hard were those tests? How high were the costs of holding on to integrity? Consider the high price Lieutenant Michael Murphy paid in summer 2005. After his team was walked over by three unarmed goatherds during a reconnaissance mission in one of Afghanistan’s most inhospitable regions, Lieutenant Murphy faced the choice of allowing the goatherds to continue on—in which case they would likely alert a Taliban reaction force—or murdering them.6 Based on the account of the recon mission’s sole survivor, Marcus Luttrell, Murphy recognized the situation as a test of integrity; right and wrong were clear to him. But he also clearly understood that the price of doing the right thing could very well be his own life and the lives of his teammates.7

We celebrate Michael Murphy because we are inspired by the strength of character required to pass such a severe test of integrity.

When we consider whether we have the character and judgment to do the right thing when confronting our own tests of integrity, it is good to remember that these tests can be intense, that character is a work in progress, and that there is always work to be done.

#5: What do I owe to others?

General obligations are duties we owe to others simply because they are fellow human beings. The Western liberal tradition embraces the idea that people, by nature, possess equal and inalienable dignity and worth. They are, therefore, entitled to rights we appropriately call “human rights.” There is consensus that all humans possess—at least—the right not to be physically harmed, not to be jailed without cause, and not to have their stuff taken from them arbitrarily.

Rights typically impose duties. When confronted with a moral dilemma, therefore, we must first ask ourselves whether the action we are contemplating keeps faith with our general obligation to respect the rights of those affected. If an act would violate another’s rights, and that person has done nothing to waive or forfeit those rights, then that act is morally impermissible.8

Special obligations are the duties we owe to others, not merely because they are fellow human beings, but because of specific roles we play, relationships we’ve formed, or promises we’ve made. If my child and a stranger are both drowning, and I can rescue only one, no one would think well of me if I chose the stranger. No one would question my decision to evacuate a burning building, yet we expect firefighters to enter them. And like firefighters who run into burning buildings, our troops are bound by their oaths to run toward the sound of the guns when prudence would suggest running away.

During Operation Red Wings, Lieutenant Murphy owed a special duty to his SEALs as their leader, but he also had a general duty to the Afghan noncombatants who had done nothing to forfeit their rights to life. Murphy correctly surmised that general obligations almost always, and certainly in this case, trump special obligations.

#6: What are the foreseeable consequences?

“He meant well” is not a phrase that often appears in fitness reports. In the military, we judge people based on outcomes, not intentions. Consequences are similarly important for evaluating moral performance. In ethical decision-making, therefore, we must consider likely results.

Like Question 4, consequentialist moral reasoning is simple, but not easy. If we are serious about our moral fitness, it is not enough to consider only the immediate outcomes of an action we’re contemplating. We have to apply our imaginations to account for everyone who could be affected by our actions in the short- and long-term. We should also consider precedent. For example, it may be that breaking a rule would result in short-term benefits. But what about the long-term harm caused by the rule-breaking precedent we’ve set?

When the USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62) collided with a container ship off Japan’s coast in 2017, two petty officers faced the daunting task of sealing off a flooding compartment. They had seconds to weigh the foreseeable consequences. Shutting the hatch would drown anyone still alive in the 30-man berthing. Not shutting the hatch would place at risk the entire ship and the rest of the 300-member crew. It would also set the precedent of putting shipmates above ship and mission.

Simple. Not easy.

#7: What would a good person do?

How should we begin to answer such a question?

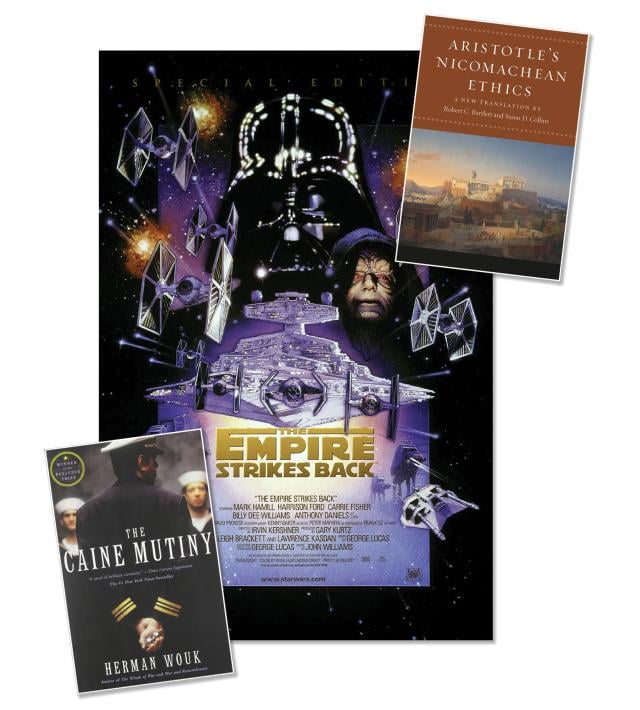

Aristotle advises a lifetime committed to the study and practice of virtue. Following his prescription, we start by learning what the great thinkers say about virtues such as courage, compassion, and honesty. Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics is a terrific resource, but so are the novels of J. R. R. Tolkien, John Steinbeck, and Herman Wouk, or movies such as Remember the Titans and The Empire Strikes Back, or conversations with our grandparents. Once we’ve learned from books, the arts, and exemplars what virtue demands, we must seek opportunities to practice what we’ve discovered. If you want to become more courageous, for example, step outside your comfort zone. Take a National Outdoor Leadership School course. Raise your hand in class. Stand up to a bully. After decades of study and practice, acting courageously will become a habit, and answering Question 7 will become effortless.

There also is a shortcut to Aristotle’s prescription. I ask my students to think for a moment and then write down the name of the most virtuous person they know, that person who always seems to do the right thing. For most of them, it is a parent, grandparent, or sibling. For some, it is Mohammed or Jesus. One of my students chose Batman. I then advise them: When confronted with a moral dilemma, the right thing to do is the action you imagine that person taking. Ask yourself WW_D in a situation like this? What would mom do? What would MLK do? What would Batman do?9 And then do it.

Concluding Thoughts

Moral theory is complex, but the moral world is far more complex, especially for those in the profession of arms. A deliberative framework will not render moral reasoning uncomplicated. The approach suggested here offers only questions; it is frustratingly light on answers. But as unsatisfying as this may feel, these seven questions can bring us closer to the answers while reducing the likelihood of missing essential moral considerations.

Too often, in the heat of battle or the heat of a really tough day, we make poor moral choices because we fail to recognize that the problem at hand warrants deliberate moral reflection. We rely on standard operating procedures that aren’t helpful. We fall back on habits that could potentially make things worse. We rush into decisions when we should take time to reflect. And even if we do see that we have crossed Kidder’s moral thermocline, we are too ready to rely on gut intuition rather than disciplined moral reasoning.

The seven questions outlined here are bulwarks against these tendencies.

1. The “situationist” tribe of moral theorists contends a person’s environment plays an outsized—some say decisive—role in moral reasoning. One well-known experiment seems to confirm the situationist claim. Few of us imagine we are capable of administering potentially lethal shocks to fellow humans, yet for most subjects in the 1963 Milgram experiment, instructions from the lab-coat-clad experimenter proved sufficient to overcome moral reservations. Milgram concludes that our disposition to obey authority can overwhelm our most basic notions of right and wrong.

2. See Rick Rubel, “Rescuing the Boat People,” in Rick Rubel and George Lucas,

Case Studies in Military Ethics, 5th ed. (Boston: Pearson-Longmans, 2014), 13–15.

3. Jessica L. Wildman, “Trust in Swift Starting Action Teams: Critical Considerations,” in Neville Stanton, ed., Trust in Military Teams (Farnham, UK: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2011), 73–82.

4. Daniel Kahneman makes a distinction between “Type I processing” (quick and intuitive) and “Type II processing” (deliberative). See Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011).

5. Stephen Coleman, Military Ethics: An Introduction with Case Studies, 1st ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).

6. Some argue that this would not have been murder on the grounds that the goatherds were serving as a reconnaissance team and, therefore, could justifiably be treated as enemy combatants. This justification collapses quickly. Even if we grant the premise that the goatherds were essentially combatants, they were in the custody of the SEALs. Once enemy combatants become prisoners, they are enemy combatants no more. In legal terms, they are hors de combat, out of the fight. Prisoners of war have recovered their rights not to be harmed, and killing them would be murder. Full stop.

7. Marcus Luttrell and Patrick Robinson, Lone Survivor: The Eyewitness Account of Operation Redwing and the Lost Heroes of SEAL Team 10, 1st ed. (New York: Back Bay Books, 2008).

8. We waive rights by choice; we forfeit them through misconduct. When boxers step into the ring or Marines cross an enemy beach, they waive their rights not to be harmed. A person who commits a felony forfeits the right to liberty. A person who threatens the life of an innocent loses the right to life.

9. As a moral exemplar, Batman is a bit problematic. He’s a vigilante. We admire his courage and commitment to justice, but only because he lives in Gotham City, a pretty awful neighborhood. Hopefully, my students will emulate Batman’s finer moral qualities while also drawing on Black Panther or Wonder Woman to complete the picture.