In the early 2000s, the threat of fast-attack craft and fast inshore attack craft in the Persian Gulf dominated tactical and operational decision-making. The littoral combat ship (LCS) was born from this environment and the operational mind-set it inspired. But the strategic seascape has changed with the reemergence of great power competition, and the Navy has shifted focus to coordinated theater campaigns. In this contemporary context, the deployment of a solitary LCS surface warfare (SUW) mission package marginalizes its combat effectiveness. Instead, the LCS deployment model should be built around a surface action group (SAG) of two or more SUW-configured LCSs.

The SAG Model

Concentration as a force multiplier in offensive military operations is not a new idea. Naval theorists Rear Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan and Sir Julian Corbett both agreed that concentration of force at sea is necessary to win decisive naval battles, gain sea control, and achieve military objectives. Naval tactician Captain Wayne Hughes believed it is critical for the “tactical commander to have the means to concentrate firepower and deliver enough of it to accomplish the mission before the enemy can bring decisive firepower to bear.”1

For much of the past two decades, surface warriors focused on missions such as air defense, strike, and ballistic-missile defense.2 The expansion and modernization of the People’s Liberation Army Navy surface fleet, however, have returned the SUW mission and SAGs to the forefront of operational thinking. The concept of distributed lethality, for example, calls for small adaptive units, known as hunter-killer surface action groups, to consolidate offensive firepower while distributing forces across space to complicate adversary targeting solutions.3 This was exercised in 2016 by three guided-missile destroyers (DDGs) in the annual Pacific SAG deployment. After the deployment, Captain David Bretz, Pacific SAG Deputy Commander, concluded, “The value of a SAG cannot be overstated.”4 Admiral Scott Swift, then U.S. Pacific Fleet Commander, added that “the combined lethality of a SAG is much greater than an individual DDG, as impressive as an individual DDG is.”5

Benefits of an LCS SAG

An LCS surface action group would improve offensive lethality, enhance mutual defense and logistics support, and increase readiness.

Improved Offensive Lethality

An LCS’s offensive capability comes primarily from weapons organic to the LCS hull, the SUW mission package, and the aviation detachment’s MH-60S Seahawk helicopter. Deploying multiple SUW-configured LCSs in a SAG would increase the targeting radius of the ships’ weapons and the lethality of their combined aviation detachments.

Two mutually supporting LCS SUW mission packages could triple the integrated sensor coverage, increasing weapons employment range.6 Multiple LCSs could combine intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) data from all SAG assets, including the embarked MH-60S Seahawks and the MQ-8 Fire Scout unmanned aircraft systems. Equipped with a multisensor targeting/surveillance system and surface-search radar, the MQ-8 is a valuable scouting platform. Two Fire Scouts operating concurrently in separate sectors theoretically could increase the surveillance range by 300 nautical miles, feeding ISR data into a common operational picture.7 The MH-60S is equipped with a Multi-Spectral Targeting System well-suited for integration into the kill chain. Two MH-60Ss and two MQ-8s would increase surveillance capacity and over-the-horizon targeting capabilities for weapons such as the Naval Strike Missile.

The helicopter sea combat (HSC) community has trained to defeat small surface vessels for more than a decade. As a close-in maritime attack platform, the MH-60S possesses a great deal of combat potential, providing “credible lethality for defense-in-depth from unmanned systems, surface combatants, and asymmetric threats.”8 Former HSC Wing Pacific Commander Captain Kevin Kennedy boasted: “We [HSC] are the best in the world at killing anything that floats.”9

The HSC community trains to the SUW mission almost exclusively using multiaircraft tactics. Weapons employment often is predicated on having a wingman available to provide suppressive cover fire. Helicopters in section also have the advantage of sharing targeting data using lasers, link tracks, and voice. Deploying an LCS independently, with a single MH-60S, runs counter to naval aviation doctrine. An LCS SAG would close the gap between helicopter employment and doctrine.

Enhanced Mutual Defense and Logistics Support

As a light combatant with limited antiship missile self-defense capability, the LCS is highly susceptible to combat damage, requiring mutual support to mitigate its vulnerabilities.10 Multiple ships provide more comprehensive sensor coverage and create overlapping fields of fire, producing a less-porous and more-layered defensive shield.

MH-60S defensive tactics also recommend employing at least two helicopters. If one helicopter is irrevocably damaged, the other may be available to render search-and-rescue support. HSC tactical publications provide a long list of formation flight benefits, including “mutual support, increased lookout for threat detection . . . flight maneuverability and flexibility to counter threats, and unity of effort.”11 The radar warning coverage area of two helicopters increases the probability of detecting the enemy. In addition, defensive maneuvering with two helicopters complicates enemy targeting solutions.

With regard to logistics, LCS SAG deployment would provide redundancies in parts, manpower, and resources. The LCS minimal-manning construct intentionally reduces personnel redundancies, so the ability to cross-deck a sailor, even temporarily, would better support contingency operations in the event of an emergency. Likewise, redundancy in equipment and supplies might drastically reduce return-to-combat-readiness times by eliminating the need to receive matériel from a supply ship or depot. A part that breaks on one vessel might be available and transferable from another ship in the SAG. Shore support elements also could benefit from the ease of servicing collocated vessels. Perhaps even more important would be the ability to share intangible resources such as experience, training, wisdom, and ideas—all of which are in greater supply when ships are operating in groups.

For an LCS deploying independently, aircraft availability and maintenance readiness hinge on the number of parts and consumables available in the aviation detachment’s packup kit. Having fewer aircraft and parts increases a commander’s risk when determining how and when to employ his or her assets. An LCS SAG would reduce single points of failure.

Increased Readiness

The best way to prepare for battle during peacetime is by operating and training in an environment that closely approximates combat. Training as a SAG heightens the realism of synthetic threat presentations and allows for external validation and evaluation. The Navy expects training to extend beyond the workup cycle and continue through deployment. Preparing and deploying SUW-configured LCSs as a SAG would improve the quality of training and the level of combat readiness.

The HSC community’s focus on multiaircraft tactics, for example, means limited training opportunities for a single helicopter: For pilots on an independently deploying LCS, less than 30 percent of eligible Seahawk Weapons and Tactics Program events can be completed, effectively halting their training and tactical advancement.12 These training and readiness pitfalls could be avoided by employing the LCS SUW SAG concept.

Challenges and Recommendations

The challenges for the LCS SAG concept are significant but not insurmountable. One obstacle is the limited number of available SUW mission packages. The LCS program includes plans for 35 vessels, but those hulls are divided among three mission packages: SUW, mine countermeasures (MCM), and antisubmarine warfare (ASW).13 The original concept was for a 40 percent reconfigurable ship, providing tactical flexibility by swapping out mission packages.143 In practice, however, each hull is assigned a primary mission package, with limited facilities and time to swap it out.

Each of the two standing SUW divisions is responsible for maintaining and fighting four LCS SUW mission packages: one for training and three for operational missions. Deploying two or more SUW-configured LCSs per SAG would require additional SUW-dedicated hulls for homeport maintenance and training. Indeed, a RAND Corp. report recommended nearly twice as many SUW mission packages as either MCM or ASW. RAND also recommended conducting major combat operations as an SUW-configured LCS SAG, while suggesting that MCM- and ASW-configured LCSs operate independently.15

During combat operations, the LCS SAG could integrate into larger strike groups, fortifying the layered defense of high-value units by pairing against smaller surface threats. Rear Admiral John Kirby, former Pentagon press secretary, called the LCS “the best swarm killer in the surface fleet.”16 During major combat operations, the LCS SAG could increase its lethality and steel its defenses through further integration with other surface combatants. Under the defensive umbrella of a destroyer or cruiser, an LCS SAG would be better protected from air and subsurface threats while conducting SUW actions. It also could integrate into a larger expeditionary strike group or carrier strike group to provide littoral security and strengthen defense-in-depth efforts, protecting the capital ship from small boat attacks. In addition, its ability to patrol the littorals could help safeguard an expeditionary strike group during an amphibious assault.

The LCS is projected to be the Navy’s second-most numerous ship class, so it is imperative that it be included in plans for major naval combat operations. With adequate planning, training, and experience as an integrated unit, the LCS SUW SAG could be a formidable offensive weapon against smaller surface combatants in a fleet-level engagement. Despite persistent criticisms, the LCS is part of the fleet, and the Navy must employ it effectively to ensure the program is remembered for its operational successes.

Past Forward

The LCS has been compared to frigates and corvettes based on its speed, maneuverability, and survivability. These small combatants historically have operated in flotillas, leveraging numerical superiority as a defensive tactic and force multiplier. During World War II, they often attacked en mass from multiple positions.1 With limited defensive capabilities, small ships relied heavily on the element of surprise, using numerical advantage and speed to prevent targeting.2

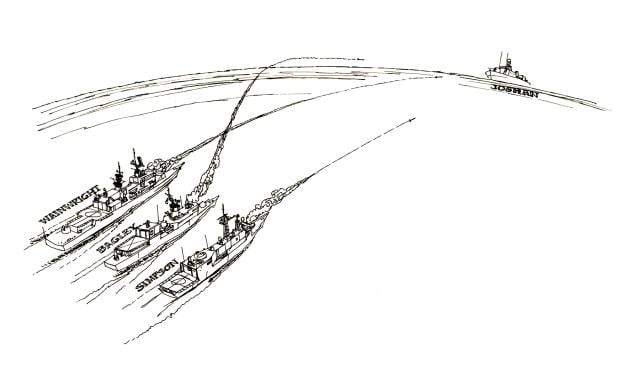

In the missile age, the efficacy of SAGs remains evident. An engagement during Operation Praying Mantis—a 1988 surface action against Iran in retaliation for the USS Samuel B. Roberts (FFG-58) mining—highlights the combat success of SAGs and the importance of mutual support. SAG Charlie, consisting of the USS Wainwright (CG-28), Simpson (FFG-56), and Bagley (FF-1069), was directed to track and engage the Iranian Kaman-class missile boat Joshan. During the engagement, the Joshan launched a Harpoon at the Wainwright. Within seconds, the Simpson launched a counterattack, striking the Joshan with a Standard Missile. The Simpson’s response was so swift that “both combatants’ weapons were simultaneously airborne.”3 Fortunately, the Wainwright was unscathed, but had the Simpson not been ready to respond, there could have been a devastatingly different outcome.

1. CAPT Wayne P. Hughes Jr. and ADM Robert Girrier, USN (Ret.), Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, 3rd ed. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2018), 194.

2. Sam LaGrone, “SNA: Navy Surface Leaders Pitch More Lethal Ships, Surface Action Groups,” USNI News, 15 January 2015, https://news.usni.org/2015/01/14/sna-navy-surface-leaders-pitch-lethal-ships-surface-action-groups.

3. VADM Thomas Rowden, RADM Peter Gumataotao, and RADM Peter Fanta, USN, “Distributed Lethality,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 141, no. 1 (January 2015).

4. MC1 Trevor Walsh, USN, “Surface Action Group: A Key to Maintaining Maritime Superiority,” Surface Warfare Magazine 54 (Spring 2017), www.public.navy.mil/surfor/swmag/Pages/Surface-Action-Group---A-Key-To-Maintaining-Maritime-Superiority.aspx.

5. Walsh, “Surface Action Group.”

6. Normal range is the radius of sensors (r) from the ship. Two ships (two circles, each with radius r), 2r apart can see 3r in one direction instead of r. Surveillance range increases further with the inclusion of air assets.

7. A1-MQ8CA-NFM-000, “NATOPS Flight Manual Navy Model MQ-8C Unmanned Aircraft System,” 1 November 2017, 4-9, 4.4.8. 150 nautical mile maximum operating range.

8. HSC Mission Statement FINAL, 28 February 2020, https://cpf.navy.deps.mil/sites/cnap-cmds2/CHSCWP/Command%20Policy%202/HSC%20Mission%20Statement%20FINAL.pdf.

9. CHSCWP Command Philosophy, 21 September 2017, https://cpf.navy.deps.mil/sites/cnap-cmds2/CHSCWP/lessons/CDRE%20VISION/HSC%20STRATEGY/CHSCWP%20Command%20Philosophy.pdf.

10. Director, Operational Test and Evaluation, “Littoral Combat Ship (LCS),” FY19 Programs, www.dote.osd.mil/Portals/97/pub/reports/FY2019/navy/2019lcs.pdf?ver=2020-01-30-115500-220.

11. SEAWOLF Manual, ch. 1.5, “Maneuver Description Guide,” May 2016, 74.

12. Helicopter Sea Combat (HSC) Seahawk Weapons and Tactics Program (SWTP), COMHELSEACOMBATWINGPAC 3502.6, 28 October 2015. Fifteen of 21 Pilot Core LVLIII/IIIi events require dual ship.

13. “LCS: The Future Is Now,” All Hands Magazine, https://allhands.navy.mil/Features/LCS/.

14. Lockheed Martin, “Littoral Combat Ship,” www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/products/littoral-combat-ship-lcs.html.

15. Brien Alkire et al., Littoral Combat Ships: Relating Performance to Mission Package Inventories, Homeports, and Installation Sites (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corp, 2007), 76, Table 8.1, 13.

16. John Kirby, “Return Fire on the Navy’s Littoral Combat Ship,” Time, 12 October 2012. https://nation.time.com/2012/10/12/return-fire-on-the-navys-littoral-combat-ship/print/.

1. John Marriott, Fast Attack Craft (New York: Crane, Russak and Company Inc, 1978), 11.

2. Bryan Cooper, PT Boats (New York: Ballantine Books, 1970), 9.

3. Harold Lee Wise, “One Day of War,” Naval History 27, no. 2 (March 2013).