The surface navy has realized that technology development trends of the past 20 years will not sustain its competitive military advantage. As such, the surface warfare community has embarked on a journey to retake the lead in technologies it has lagged in developing, such as hypersonics, directed energy, and autonomy, as well as revitalizing the methods used to develop these technologies. The speed at which it has recently unveiled and integrated new weapons and sensors into the fleet is unprecedented in my 20-year career. However, this emphasis on a faster and more agile technology development ecosystem has not bled over into readiness and maintenance.

As the commanding officer of a recently deployed Baseline 9 Flight I guided-missile destroyer (DDG), I have seen firsthand the amazing capabilities these ships bring to bear. From my last sea tour as a department head on a Baseline 5 Flight I to stepping on board as the executive officer, the difference is visually striking, especially in the upgraded combat information center (CIC). After deploying to Fifth Fleet in 2019–20, I found hope that the combat power and reach of this new baseline meant the narrative of fading U.S. naval power in the face of an expanding Chinese Navy is greatly overblown. In the words of Admiral Arleigh Burke, “This ship is built to fight.”

But the Navy must continue to be ready. Equally striking during my tour was the challenging material condition of the ship. The Flight I DDGs are approaching their originally intended 35-year service lives and are showing their age when needed most. During World War II in the Pacific, the number of U.S. surface combatants was as critical as the ability to keep those ships at sea from engagement to engagement with limited repair ability. To achieve the numbers necessary in a future war, the Flight I DDGs will continue to be a crucial part of the surface navy far past their intended service life. However, after two decades of consuming service life through abnormally high operational tempo and deferred maintenance, the Navy’s current maintenance philosophy will not recoup the material condition lost and achieve a cost-effective life extension.

How We Got Here

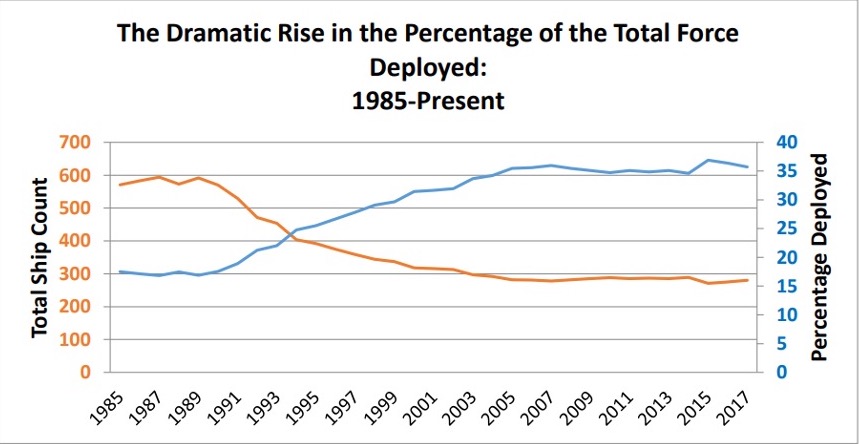

As my ship slipped past its original selected restricted availability (SRA) completion date with at least another five months to go, I asked myself, how did the Navy get here? The Strategic Readiness Review by the Honorable Michael Bayer and Admiral Gary Roughead and the Balisle Report, among others, give a clear picture of what every surface warfare officer has experienced over the past 20 years: a surface fleet that has delivered a historically high level of operational availability while shrinking in size and budget. The figure below from the Strategic Readiness Review depicts this outcome. By 9/11, fleet size had largely stabilized around 300 ships just as the nation and the Navy were beginning two decades of sustained operations in the Global War on Terror.

While the Defense Department received substantially higher budgets during this time, the focus was on the land components in Operation Enduring Freedom and then Operation Iraqi Freedom. The Navy did receive additional funding, however much of this came from the overseas contingency operations fund, which is not intended to recoup readiness costs associated with the increase in operational tempo. Concurrently, the normal Navy budget was under pressure from multiple continuing resolutions and the Budget Control Act of 2013, ultimately leading to sequestration. This forced Navy leaders at the time to make difficult decisions and prioritize the most critical missions while using maintenance and modernization accounts as bill payers to meet the needs of those operations.

I spoke to a former member of the surface type-commander staff who specifically remembered being in the room about 10 years ago when my ship’s programmed structural repair package was cut in half because of funding constraints—that bill has come due, with compound interest. This, combined with an ever-evolving Optimum Fleet Response Plan that uses creative ways to achieve the higher operational tempo (e.g., forward deploying ships, shortening SRAs, accelerated training cycles, and more frequent “Composite Training Unit Exercise and Go” deployments), cost maintenance time, which has led to a surface force that has overconsumed service life.

This was not how Arleigh Burke–class destroyers were designed to be maintained. The original service life of the Flight I and Flight II DDGs—commissioned from 1991 through 1999—was planned to be 35 years. Thus, they should decommission between 2026 and 2034. Any ship’s planned service life consists of overlapping predictions and assumptions of operational tempo, SRA cycles and duration, continual maintenance, and a host of other factors. The Navy ordered the first DDG-51 in fiscal year 1985 at the height of the Cold War, when the surface fleet exceeded 600 ships, each of which spent an average 18 percent of its life deployed. Since 2001, the roughly 300-ship fleet has spent approximately 30 percent of its life deployed (see figure above).

The original assumptions that went into a 35-year service life for the class have not been validated, much less revised, over time despite radical alterations to the ships’ employment and maintenance. Therefore, DDG-51, now 30 years old, has expended far more than 30 years’ worth of service life. While the true number is unknowable, it is indisputable that the surface warfare community did not make the correct assumptions in 1985 when estimating a 35-year service life. Despite comments from Navy leaders in congressional testimony last year, if recent history with the Ticonderoga-class cruiser service-life extension program teaches anything, it is that it is unlikely the first Arleigh Burke–class DDGs will decommission in the next 5 years—there is nothing to replace them.

Where We Are

Ship commanding officers and the surface navy at large are sending ships into potential conflict against an ever-advancing adversary with an unknown level of material-condition risk. While from my position as a recent commanding officer, I cannot speak to the fleetwide data directly, I see the effect on the waterfront—particularly when it comes to Flight I DDGs. SRAs are getting longer, unforeseen issues routinely delay SRA completion, SRA growth work is expanding, and emergent maintenance availabilities are becoming routine. Older DDGs, such as my former ship, are a leading indicator of what is to come for the rest of the fleet—now is the time to enact needed changes.

Despite a maintenance strategy intended to predict the work necessary, the first 20 percent of an SRA is discovery. The notional intent of this discovery phase is to plan for the next availability. However, in the discovery phase the worst material issues are identified and only the most extreme repairs are completed in the current availability. New repairs not part of the original work package are proportionally more costly and delay the schedule—the opposite of the Navy’s “on time, on budget” philosophy.

In addition, the commander of the Surface Maintenance Engineering Planning Program (SurfaceMEPP), who has the responsibility for culling lessons learned from SRAs and determining ship-class issues so that future SRAs can address known problems, dictates which tanks and voids must be opened and inspected. Specifically for my SRA, SurfMEPP directed 18 tanks and voids opened and inspected by a Mid-Atlantic Regional Maintenance Center ship-building specialist (SBS). There were an additional 32 tanks and voids that contractors had to open so that work could take place in an adjacent space—SBS professionals did not inspect them. This created two perverse incentives. First, the optimum solution for availability success is to defer the work despite the material effect on the ship; and second, if the Navy does not know about it, it does not need to fix it.

The surface community is fighting the symptoms while ignoring the disease. Until it truly understands the effect of 20 years of deferred maintenance and higher operational tempo, the force is operating with a “known unknown” risk. When USS Yorktown (CV-5) put to sea to fight at Midway after 48 hours in a dry-dock, there was no illusion as to the risk the Navy and her crew were taking. It was a calculated risk decision that ultimately proved correct despite the loss of the ship. Today, ships are sailing around with an unknown risk that could prove decisive and disastrous in combat. The first step in solving the problem is acknowledging there is one, then apply the same level of effort to advancing maintenance as to advancing lethality.

Where We Need to Go

Move maintenance into the 21st century. Artificial intelligence is revolutionizing everything from intelligence collection and analysis to modular ship design. Computing power now used in lethality is equally valuable for maintenance. AI could be used to create a real-time model for every hull—a “virtual hull” DDG-51v. Through the combination of predictive metrics and real-time events, a hull-specific model can be used to more accurately analyze the state of a ship’s material readiness. All the disparate inputs—manning and ship’s force preservation, deployment lengths, run-time on equipment, deferred work out of continuous maintenance availabilities or SRAs, delayed or deferred dry dockings, departures from specification, inspection results, etc., can be pooled to give fleet and maintenance leaders a highly accurate estimate of the actual material condition as well as the potential risk of a material casualty while deployed. Regional maintenance centers and the type commander already have most of the data; it is simply being underutilized. DDG-51v would also be a tool to determine the effectiveness of current predictive indicators as well as modeling potential repairs. I am keenly aware that we are using a lot of metrics across the fleet today, but, based on my view from the deckplates, in the age of 21st-century data analytics, the Navy is missing a chance for a quantum leap in maintenance effectiveness.

Change the philosophy and plan with the end in mind: Fix the ship. Today’s singular focus on one metric—“on time, on budget”—incentivizes the deferral of the structural repairs most related to ship service life. The philosophy during an SRA should be “maximize the structural repair of the ship.” This has ramifications for contracting and planning of SRAs, but it is the only way to recoup lost service life. A ship’s most structurally ready state is immediately following an SRA. It will deteriorate from there until the next SRA. The focus must be on maximizing material readiness.

Open and inspect whenever possible. The surface warfare community must take every opportunity to open and inspect tanks and voids. SurfMEPP collects data to determine where the problems exist. However, the surface navy is not maximizing opportunities to learn. The 32 tanks that were opened but not inspected were pumped and opened by a contractor, gas freed, and a fire watch would enter while work was ongoing. Ship’s force personnel entered, to conduct our own inspection, but this is not the equivalent of a trained engineer. The argument was that these were not funded in the package. But the real reason seemed to be, “If we look, we might find something, and then we would have to pay to fix it”—to which I say, “Yes, that’s the point.”

Move oversight and ownership back into the surface warfare officer community—establish readiness chains of command. The 2010 Balisle Report identified the disestablishment of the readiness squadrons in 1995 as a cause of reduced material readiness in the fleet. Today, operational squadrons have the responsibility to prepare their ships for combat and ensure their ships successfully execute their SRAs. These squadron staffs are not manned and resourced for both of these tasks. These staffs are typically bifurcated into an N-4 staff that monitors maintenance and availabilities and the rest of the staff that primarily focuses on warfighting. The limited staff of rotational officers and senior enlisted do not have the continuity to capture and apply lessons learned, understand long-term trends and effects, and articulate holistic risks. Readiness squadrons can advocate for their ships’ material condition against the ever-present need to be operational. The establishment of a readiness squadron in Japan following the Strategic Readiness Review is an example that could be emulated.

Any ship’s commanding officer on the waterfront today will attest that the maintenance planning process is mind-numbing and exhausting while not meeting the mark. Something must change—and soon—if the Navy wants ships to last and be ready to fight tonight. Depot-level maintenance must shift from “on time, on budget,” to a philosophy that is intentionally planning to recoup the years of ship life lost over the past 20 years. By accepting that the material condition of a ship is likely to be substantially worse than can be assessed while operational, Naval Sea Systems Command can budget for, and regional maintenance centers can plan for, the anticipated higher workload. Fleet commanders must be realistic and include flexibility in SRA schedules to absorb inevitable delays. Ship life is a finite resource, and the Navy ignores the current trends at its peril.