Japan arguably has more vital connections to the sea than any other major nation. Its complex geography—an archipelago of some 6,850 islands with 126 million citizens—makes it a coastal state with the eighth largest exclusive economic zone (EEZ). This vast marine space is 12 times larger than the nation’s landmass. Japan signed the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) on 7 February 1983 and ratified it on 20 June 1996. UNCLOS remains a critical and stable governance framework essential to Japan’s connections to the sea, national marine policies, and future maritime fortunes.

Japan’s mineral resources are limited; most notably, it lacks crude oil and natural gas. National energy statistics for 2018 indicate Japan remains highly dependent on fossil fuels, with nearly all of its oil imported by sea from the Middle East. Unimpeded use of sea lines of communication and freedom of navigation are critical to its economic survival.

The strategic need for a large merchant fleet is reflected in 2019 data that indicates Japanese companies own 11.5 percent of the world merchant shipping fleet, second only to Greece. Its shipyards delivered 14.5 million gross tonnage in 2018. Naval shipbuilding and global markets for eco-friendly and technically advanced ships may provide viable pathways ahead.

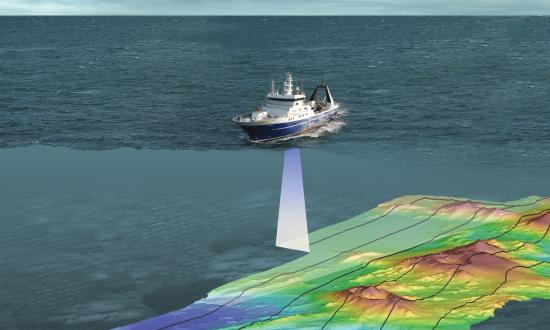

The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force—comprising 155 ships (40 destroyers) and 50,000 personnel—is focused on national defense, operating with allies, U.N. peacekeeping, and maritime interdiction forces. The Japan Coast Guard, a civilian maritime organization of 15,000 personnel, operates a highly capable fleet of some 450 patrol vessels and craft, and aircraft, to conduct multiple missions (including law enforcement, hydrography, and more) in its EEZ and beyond.

Japan is a major fishing nation, ranking seventh in tonnage caught in 2018. It was ranked as the world’s leading fishing nation during 1970–91, but coastal state establishment of 200-nautical-mile EEZs, with licenses, catch limits, and protected-area bans reduced opportunities and transformed Japan’s once global fishing fleet. During the same period, Japan built a world-class marine science, fisheries, and ocean technology research community. One example is the deep-sea drilling ship Chikyū, operating since 2007, which has been coring in oceanic earthquake zones and into the continental shelf.

Japan took a significant step in addressing its roles as a 21st-century ocean state with enactment of the Basic Act of Ocean Policy in April 2007. This law provides a framework for an integrated and comprehensive view of the nation’s many maritime relationships. A Headquarters for Ocean Policy was created and worked with the Prime Minister to guide the development of Japan’s ocean policy plans in 2008, 2013, and 2018. The overarching theme in the Third Basic Plan is maritime security, which mandates a whole-of-government approach and includes defense, law enforcement, foreign policy, marine traffic safety measures, and responding to marine natural disasters. The 2018 plan includes eight additional ocean policy measures: to promote industrial use of the ocean; maintain and conserve the marine environment; strengthen maritime domain awareness; improve scientific knowledge; preserve remote islands and develop the EEZ; promote Arctic policy; enhance international collaboration and cooperation; and develop human resources to support the oceanic state and educate citizens about the oceans.

Japan’s future as an oceanic state faces many challenges. Maintaining secure sea lines of communication and defending its large EEZ remain fundamental to its survival. Sustaining world-class shipbuilding and fisheries will be formidable challenges amid strong global competition. Warming of its surrounding seas and increasing plastics in its coastal waters pose serious threats to its marine ecosystems and a sustainable ocean economy. Responding to sea level rise and coastal flooding will require large infrastructure investments. Marine science, ocean technology, ocean observing, and strengthening maritime domain awareness will call for enhanced funding.

The stakes are high for Japan as the world’s third largest economy and one of the nations most dependent on the oceans.