Since late last year, a number of Russian news articles have linked Operation Grom, a series of submarine operations in fall 2019, to Operation Atrina, a perceived success story in which five Victor III nuclear-powered attack submarines (SSNs) reportedly reached the U.S. East Coast undetected and operated there from March to May 1987. The U.S. Navy released a statement on 7 April 1987 saying the submarines were operating near Bermuda and that it had dispatched forces to monitor them. When reporters asked then–President Ronald Reagan during a Pentagon press conference whether he was concerned about the Soviet submarine activity, he joked, “You’re asking a civilian? I’m always concerned about them.”1

Three decades later, the objectives of Operation Atrina still are not entirely clear. Nevertheless, the operation has attained something of a mythological status as the storied apex of the Soviet Navy and relevant to Russia’s present submarine operations.

According to Western news reports at the time, the five Soviet subs transited to the western Atlantic and simulated wartime strikes against two major U.S. East Coast naval bases. Officials told United Press International that U.S. Navy P-3 antisubmarine aircraft “constantly” watched the Soviet boats. In addition, U.S. and NATO surface combatants joined the hunt in a “rare bonanza for practicing wartime antisubmarine warfare tactics.”2

Then–Secretary of the Navy John Lehman indicated the Victor IIIs had “sortied from their Kola bases to the Bermuda Triangle southwest of Bermuda, coordinating their operations with Tu-20 Bear D reconnaissance and missile guidance aircraft flying from bases on the Kola [Peninsula] and from Cuba.” He believed Moscow was “trying to test U.S. Navy and allied surveillance and other reactions and ascertain relative capabilities.”3

Russian-language sources have claimed Moscow had other goals. Almost every Russian account over the past three decades has developed out of articles published by Admiral Vladimir Chernavin, who was commander-in-chief of the Soviet Navy from 1985 to 1991 and later the first commander of the Russian Federation Navy. The perceived success of Atrina, which Chernavin described as a “small Battle of the Atlantic,” proved him to be a worthy successor to the man responsible for the quantitative and qualitative buildup of the Soviet fleet from the 1960s to the 1980s, Admiral Sergei Gorshkov.4

Operation Atrina

Atrina was a follow-on to Operation Aport, which took place between May and July 1985 and involved five or six Soviet submarines operating in the western Atlantic. Chernavin and Vice Admiral Anatoly Shevchenko, the lead planner for both operations, were consistent in their descriptions of Aport’s objectives:First, the Victor I, II, and III subs were supposed to determine the patrol areas of and track U.S. ballistic-missile submarines (SSBNs) between the Newfoundland Grand Banks and Bermuda. Second, the submarines, in concert with surface ships and Tu-142M maritime patrol aircraft, were to study the tactics of the U.S. P-3s. Shevchenko, at the time a captain of the 1st rank, coordinated the submarines, surface ships, and aircraft from on board the naval survey ship Kolguyev and the Lira, a state-of-the-art intelligence-collection ship.5

Russian authors have claimed Aport was a glowing success. In his memoir, Shevchenko said the submarine K-147 used a wake-detection system called “Toukan” to track a U.S. James Madison–class SSBN for five days.6 Another submarine, the K-324, reportedly tracked three U.S. SSNs and SSBNs, and the Soviet aircraft allegedly were able to monitor several SSNs as they sortied. Naturally, the Russians contend the U.S. submarines were unable to track the Soviet subs—however skeptical one should remain about such claims.7

Atrina’s March–May timeframe sought to mitigate some of the issues the Soviet submariners had encountered during Aport and reflected lessons learned through operational experience and meticulous planning. During Aport, the Soviet submariners encountered challenges operating their equipment in the warmer waters and algae accumulations of the Sargasso Sea. It took nearly two years to prepare the Atrina submarines for their journey and to train the crews to work in concert with the surface ships and patrol aircraft assigned to the mission.

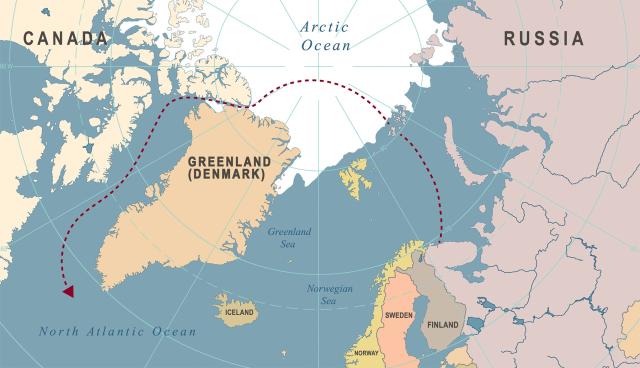

Using a combination of guile and operational security, the Victor IIIs allegedly caught U.S. and NATO forces unaware. While Soviet submarines typically went on combat patrols alone, less often in pairs, Atrina was the first time the Soviets sent an entire division to sea in quick succession. Moreover, the submarines did not take the most direct and typical course from their base at Zapadnaya Litsa through the Barents Sea, into the Norwegian Sea, and then out into the Atlantic after exiting the Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom (GIUK) Gap.8 Reportedly, the Victor IIIs conducted an under-ice transit and then traveled south along the western side of Greenland to avoid NATO patrols and the Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS) monitoring networks.9

The Soviets supposedly used misdirection during both Aport and Atrina to give the impression that the submarines were heading to the Mediterranean rather than the Atlantic. The planners kept a tight lid on the information, and even the boat commanders only found out at the last moment where their ships were going and why.10 The name “Atrina” has no meaning in Russian (or English) and was invented to prevent any logical connection to the operation. In addition, the submarines participating in Atrina used technical deception. Chernavin authorized use of a sonar counteraction device that originally was reserved for actual combat operations, as well as noise simulators.11

In a 1994 Pravda article, Chernavin wrote, “In addition to all other tasks, the division was intended to reveal the underwater and surface shipping routes in the same part of the ocean, which was poorly tracked by other means of maritime intelligence.”12 With a touch of bravado, he added, “It was necessary to teach a little lesson to the arrogant ‘probable enemy’ and show that, if necessary, we can become ‘elusive avengers,’ that is, to act covertly enough to strike back, ‘a retribution [second] strike.’” Tying the submarine operations to diplomatic initiatives in arms control then under way, Chernavin said the success of the mission “would immediately reflect on the tone of many international negotiations” and would “counter the [American] ‘policy of gunboats’ with an adequate ‘policy of submarines.’”13

In an article in Morskoi Sbornik in 2006, Chernavin was more measured. “It was necessary,” he claimed, “to find, train, and practically test the effectiveness of secured deployment methods of first of all nuclear submarines in the Atlantic, as well as to demonstrate that if required we can become undetectable, ready to covertly deliver strikes as well as to deliver nuclear weapons counterstrikes at the surface targets located in the hostile territory.”14 Clearly proud of his team’s accomplishments, the former commander-in-chief proclaimed, “The missions were fully accomplished: U.S. and British submarines deployed during the operation in the Atlantic were detected; the underwater and surface navigation situation in the Atlantic region insufficiently described by other naval intelligence means was disclosed. All our SSNs successfully returned home.”15

The deployment provided the Soviets with an opportunity to test new equipment on board the Victor IIIs, including the “Ritsa” hydroacoustic detection system and the hydroacoustic decoy, to deny or degrade NATO’s anti-submarine capabilities. Ritsa reportedly used a digital computer with advanced algorithms to passively detect NATO surface ships and other submarines at great distances.16

Thus, Russian sources add that, in addition to simulating attacks on U.S. naval bases and provoking and then monitoring a response, Atrina’s aims also included discovering and mapping U.S. SSBN operating areas; developing acoustic signatures for U.S. SSNs and SSBNs; testing communication methods and coordination among submarines, surface ships, and aircraft; monitoring ship traffic from the GIUK Gap down to the Sargasso Sea and the Gulf of Mexico; adding credibility to the Soviet Union’s second-strike capability; giving the U.S. Navy and NATO allies a black eye; and highlighting the success, bravery, and capabilities of the Soviet military.

Russian writers have emphasized that the United States and NATO did not detect the Soviet submarines until after they had completed their missions, whereas Western reports at the time claimed the submarines were tracked constantly.17 The truth probably lies somewhere in the middle.18

What’s Old is New Again

On 29 October 2019, Norwegian NRK television reported that Russia was using Operation Grom’s weapons tests and exercises as a cover to flush its submarines and probe the NATO response.19 Citing Norwegian intelligence, NRK reported that Moscow wanted to show it could once again threaten the U.S. East Coast and get far into the Atlantic. It noted that two deep-diving, titanium-hulled Sierra-class SSNs were operating in the Norwegian Sea, in addition to Russia’s most advanced, cruise-missile-carrying Yasen-class nuclear multipurpose submarine, the Severodvinsk.

The Russian-language press wasted no time hearkening back to Operation Atrina. Writing in Svobodnaya Pressa the same day, Russian military expert Viktor Sokirko claimed a dozen submarines of the Northern Fleet had successfully rehearsed a wartime, covert breakout to U.S. shores and said Grom could be called “Atrina 2.”20 Following suit a few days later, Dmitry Boltenkov wrote in pro-government Izvestiya that the Russian submarine forces were demonstrating their might, “so one can call the current exercise ‘Operation Atrina 2019.’”21 Boltenkov added that Russia’s two-month-long exercise—which included eight nuclear-powered boats—represented the deployment of every combat-ready submarine in the Northern Fleet.22

The U.S. military and defense establishment also were paying attention and making the connection back to the Cold War. Admiral James Foggo, then-commander of U.S. Naval Forces Europe and Africa and NATO’s Allied Joint Force Command, said in December 2019, “We’re seeing a surge in undersea activity from the Russian Federation Navy that we haven’t seen in a long time. Russia has continued to put resources into their undersea domain; it’s an asymmetric way of challenging the West and the NATO alliance, and actually they’ve done quite well.”23

At a Senate hearing two months later, U.S. Air Force General Tod Wolters, the NATO supreme commander, noted that the United States witnessed “a 50 percent increase in the number of resources in the undersea that Russia committed to both those out-of-area submarine patrol operations” in 2019 compared to a year earlier.24

Separately, Vice Admiral Andrew “Woody” Lewis, head of the reinstituted Second Fleet, summarized for an event hosted by the U.S. Naval Institute and the Center for Strategic and International Studies: “Our new reality is that when our sailors toss the lines over and set sail, they can expect to be operating in a contested space once they leave Norfolk.” Lewis added, “We have seen an ever-increasing number of Russian submarines deployed in the Atlantic, and these submarines are more capable than ever, deploying for longer periods of time, with more lethal weapons systems. . . . As such, our ships can no longer expect to operate in a safe haven on the East Coast or merely cross the Atlantic unhindered to operate in another location.”25

So What?

Whether the link between Grom and Atrina is intended for Russian domestic audiences, a means of strategic messaging, or a combination thereof, looking at interpretations of the original Operation Atrina yields a few points worth consideration.

As during the Soviet Navy’s heyday, Moscow may be signaling that Russia’s submarines can still break out into the Atlantic and get to within cruise-missile range of the continental United States. If Russia does have this capability, then Vice Admiral Lewis is correct that the East Coast is no longer a safe haven.

After the demise of the Soviet Union, just as in the later years of the Cold War, Moscow lacked the means to conduct an operation on the scale of Grom or Atrina. That has changed. Moreover, Moscow’s ability to conduct such surges is growing as new submarines—such as the Improved Yasen-class—enter service. Russia also has been upgrading older platforms, such as the Akula attack submarines, in fits and starts to add capabilities and service life. As the numbers of Russian submarines increase, it is fair to predict more operations like Grom or Atrina in the near future.

However, operations such as Atrina may have unintended consequences. The U.S. Navy used increased Soviet activities, such as Operation Atrina, to bolster its antisubmarine capabilities in the 1980s, funding new-generation nuclear-powered attack submarines (the Seawolf and then the Virginia classes) and antisubmarine aircraft (P-3Cs and eventually the P-8 Poseidon).26 A more aggressive Russia may have the counterproductive effect (for Moscow) of provoking the development of new countermeasures by the United States, encouraging U.S. forces to operate closer to Russian shores, and providing advanced ASW training for the U.S. Navy.

1. UPI, “Soviet Nuclear Submarine Pack Simulates Strike at U.S. East Coast Naval Bases,” The Ottawa Citizen, 9 April 1987, A6.

2. UPI, “Soviet Nuclear Submarine Pack.”

3. John Lehman, Ocean’s Ventured: Winning the Cold War at Sea (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2018), 221–22. Lehman called the plane a Tu-20, but the Soviet Union manufacturer, Tupolev, stopped using that designation in the 1950s. The maritime patrol version of the Tu-95 is known as the Tu-142.

4. Fleet Admiral Vladimir Chernavin, “Bumazhnye korabliki v more zhizni [Little Paper Boats on the Sea of Life],” Pravda, 9 February 1994, 4.

5. Vladimir Lodkin, “How Soviet Submarines Beat the Americans: Operations ‘Aport’ and ‘Atrina’ Proved the High Potential of the Russian Navy,” Nezavisimaya Gazeta, 27 July 2018, http://nvo.ng.ru/wars/2018-07-27/12_1006_submarine.html.

6. Lodkin, “How Soviet Submarines Beat the Americans.” On Soviet/Russian nonacoustic detection means, see David Hambling, “How the Soviet Union Snooped Waters for Enemy Subs—Without Sonar,” Popular Mechanics, 23 October 2017, www.popularmechanics.com/military/navy-ships/a28724/submarine-sonar-soks/.

7. Lodkin, “How Soviet Submarines Beat the Americans.” The Russian claim is highly suspect. See Richard Halloran, “A Silent Battle Surfaces,” The New York Times, 7 December 1986, https://nyti.ms/29Bv9oW.

8. Chernavin, “Bumazhnye korabliki v more zhizni,” 4.

9. Edward C. Whitman, “SOSUS: The ‘Secret Weapon’ of Undersea Surveillance,” U.S. Navy Public Affairs, www.public.navy.mil/subfor/underseawarfaremagazine/Issues/Archives/issue_25/sosus.htm.

10. Chernavin, “Bumazhnye korabliki v more zhizni,” 4.

11. Chernavin, “Bumazhnye korabliki v more zhizni,” 4.

12. Chernavin, “Bumazhnye korabliki v more zhizni,” 4.

13. Chernavin, “Bumazhnye korabliki v more zhizni,” 4.

14. V. N. Chernavin, “Operation Atrina: History Lessons,” trans. East View, Military Thought 15, no. 2 (2006): 174–76.

15. Chernavin, “Operation Atrina: History Lessons,” 174–76.

16. Theodosius, “Ritsa 2000,” 16 January 2008, http://nvs.rpf.ru/nvs/forum/archive/92/92962.htm.

17. Don Kirk, “Fleet of Soviet N-subs Prowls off East Coast; Navy Monitors Unusual Deployment,” USA Today, 8 April 1987, 06A.

18. When Gary Weir, author of Rising Tide: The Untold Story of the Russian Submarines That Fought the Cold War, had his translator ask Shevchenko if the Soviets had tried to use the Gulf Stream as a cloak from SOSUS arrays on the eastern seaboard of the United States, the admiral became upset and deflected. C-SPAN, 3 August 2005, www.c-span.org/video/?188814-1/rising-tide-russian-submarines-fought-cold-war.

19. Tormod Strand, “Hemmelig ubåt-operasjon: Målet er å vise at Russland kan nå USA,” 29 October 2019, www.nrk.no/norge/hemmelig-ubat-operasjon_-_malet-er-a-vise-at-russland-kan-na-usa_-1.14761298.

20. Viktor Sokirko, “Operation Atrina-2: Russian Submarines Put All NATO fleets ‘On Their Ears,’” Svobodnaya Pressa, 31 October 2019, https://svpressa.ru/war21/article/247832/.

21. Izvestia website, 3 November 2019. Available in translation via ProQuest: https://search.proquest.com/docview/2312073689?accountid=322.

22. Izvestia website.

23. Sam LaGrone, “U.S. Fleet Created to Counter Russian Subs Now Fully Operational,” USNI News, 31 December 2019.

24. Joel Gehrke, “U.S. Has ‘Sufficient Visibility’ into Russian Submarines But Can’t Find Them ‘100% of the Time,’” The Washington Examiner, 25 February 2020, www.washingtonexaminer.com/policy/defense-national-security/us-has-sufficient-visibility-into-russian-submarines-but-cant-find-them-100-of-the-time.

25. Megan Eckstein, “As Russian Submarines Lurk, 2nd Fleet Conducting Tougher Training of East Coast Ships,” USNI News, 4 February 2020.

26. “Five Soviet Submarines Reported Off Bermuda,” 8 April 1987, Special to The New York Times, A17.

1. N. Polmar and K. J. Moore, Cold War Submarines: The Design and Construction of U.S. and Soviet Submarines (Washington, DC: Brassey’s, 2004).

2. See N. Polmar, “The Typhoon Solution,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 121, no. 8 (August 1995): 88.

3. Igor Spassky and Viktor Semyonov, eds., Submarines of the Tsarist Navy (Annapolis, MD: Naval institute Press, 1998).