On 2 June 2020, Russian President Vladimir Putin released Basic Principles of State Policy of the Russian Federation on Nuclear Deterrence, an unprecedented six-page document describing Russian nuclear weapons doctrine.1 It constitutes Moscow’s first-ever publicly available, official policy on deterrence—one aimed at foreign audiences. Russia analyst Nikolai Sokov notes that the document does not contradict current military doctrine, which has “demonstrated remarkable consistency during the past two decades.”2 It builds on December 2014’s The Military Doctrine of the Russian Federation as well as the December 2015 (Russian) National Security Strategy, and it consolidates messages from Moscow’s past public statements, documents, and military exercises.3Basic Principles consists of four sections: general provisions; the essence of nuclear deterrence; conditions for the use of nuclear weapons; and tasks and functions of federal government authorities and organizations.

As a premise, Basic Principles explicitly states that “guaranteed deterrence” is one of Russia’s highest national priorities.4 The general provisions section provides insight into why such a document is needed, while the document as a whole appears intended to debunk misconceptions about Russia’s nuclear strategy, mapping the evolution of the changes and possible arenas for arms control. Ultimately, though, it prompts new questions for Western consideration.

Why Now?

Basic Principles was released against a dire backdrop: Russia maintains a stockpile of 4,310 nuclear warheads, and traditional arms control is deteriorating.5 It thus has two motivations. First, it attempts to frame the United States as the primary offender in the collapse of long-standing agreements, including the U.S. withdrawal from the 1987 Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty in August 2019 and the nuclear modernization efforts outlined in the U.S. Department of Defense 2018 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR).6 Second, Basic Principles roots Russian strategy in traditional deterrence theory and even suggests the possibility of finding common ground for future treaties, although this might eventually prove mere rhetoric.

The nuclear deterrence section underscores deterrence’s defensive nature, illustrating (without naming) Thomas Schelling’s concept of “deterrence by punishment” in retaliation for aggression, which has dominated Russian theory since the 1990s.7 It differs from “deterrence by denial,” which bolsters defenses to make offensive strikes impossible. In paragraph 6, Moscow claims explicit compliance with “universally recognized principles and norms of international law,” and it lists mili-tary threats to be deterred in paragraph 12: the build-up of weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) and associated delivery vehicles by potential adversaries; deployment of missile defenses, short- and medium-range ballistic and cruise missiles, hypersonic vehicles, nonnuclear high-precision weapons, unmanned aerial vehicles, and directed energy weapons; and the development of outer space systems. In other words, existence of these capabilities warrants defensive deterrence, but none is an auto-matic trigger for use. By highlighting the threat of “nuclear weapons and their delivery means in the territories of non-nuclear weapon states,” Basic Principles echoes Russia’s known disapproval of nuclear sharing within NATO—particularly the presence of U.S. B61 bombs in Europe

Section III discusses conditions that would justify actual use when deterrence fails. In some ways, it responds to the recent U.S. NPR’s codified justifications for use. While capturing the spirit of the two previous Russian military doctrines, paragraph 19 outlines four conditions that would allow (but do not necessitate) nuclear employment:

- Use of nuclear or other weapons of mass destruction by an adversary on Russian or allied territory

- An attack on critical government or military infrastructure that could debilitate a nuclear response

- Aggression with conventional weapons when “the very existence of the state is in jeopardy”

- “Reliable data” that Russia (or an ally) is under a ballistic-missile attack

Two years ago, the NPR identified “attacks on U.S., allied, or partner civilian populations and infrastructure and attacks on U.S. or allied nuclear forces, their command and control, or warning and attack assessment capabilities” as significant nonnuclear strategic attacks. Russia has now confirmed a similar view. The NPR also threatened nuclear retaliation for use of the same advancements in conventional technology mentioned in Basic Principles. Ultimately, Basic Principles—like the NPR—advocates for a nuclear triad to preserve the survivability of land-based forces, as well as scalable nuclear options in the event of a conflict.

Escalate to De-escalate?

The somewhat mystifying phrase “escalate to de-escalate” does not actually appear in official Russian doctrine, but in recent years it has dominated the debate about when Moscow might employ nuclear weapons. Russia’s 2017 naval doctrine claims “the willingness and determination to employ force, including non-strategic nuclear weapons” strengthens deterrence during escalation, and Western analysts such as Matthew Kroenig and Elbridge Colby have described the concept as using low-yield nuclear weapons early on the battlefield to attain an “advantageous” outcome. The NPR accepts that Russian doctrine includes such a policy but explicitly attempts to discourage it.8 The concept appears to have first emerged in a 1999 paper in the Russian military journal Voennaya Mysl, positing how nuclear use could convince an adversary to cease action in conventional conflict. It seems, however, this thinking is confined to a coterie of Russian “escalation” advocates, who have failed to lower the official threshold for use.9

Significantly, paragraph 19 of Basic Principles contains no language permitting such a low threshold, although paragraph 4 in the general provisions section does say: “In the event of a military conflict, this Policy provides for the prevention of an escalation of military actions and their termination on conditions that are acceptable for the Russian Federation and/or its allies”—words that at least hint at an “escalate to de-escalate” doctrine. But Russia analysts Nikolai Sokov and Olga Oliker believe paragraph 4 actually is an attempt to end the misconception—to soften the language from preemptive, “advantageous” aims to an “acceptable,” last-resort option. Paragraph 15 supports this interpretation. It lists key principles of nuclear deterrence—including unpredictability of scale, time, and place for employment of forces—and consequently emphasizes the role of ambiguity. Credibility would be undermined if Russia clearly disconnected the “deterrence” in paragraphs 4 and 12 from “use” in paragraph 19.

The latter, however, clarifies that Russia will not deploy nuclear weapons for mere battlefield advantage, because use is only warranted for the predefined existential threats. Oliker says that if Russia does decide to use nuclear weapons, it will still try to “prevent further escalation and end the conflict as favorably (or acceptably) as possible for itself . . . to include an intermediate step of reestablishing deterrence, and potentially the acceptance of something short of full victory.”10 In other words, de-escalation is not a warfighting tool; it is a tool of deterrence.

‘Launch on Attack’

While much of Basic Principles reaffirms decades-old trends in Russian policy, one distinct change is the official validation of the “launch on attack” concept against ballistic missiles, called out in paragraph 19. Originating from the Cold War, the launch on attack principle (also known as “launch on warning”) had the potential to enhance deterrence by assuring retaliation, since a first strike would hit only empty silos. At the same time, it greatly amplified the risk of accidental launches and erroneous warnings, best exemplified in a 1983 incident in which Soviet Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov refused to respond to a false trigger.11 Today, the launch on attack posture permits Moscow to retaliate while an incoming attack is under way, before receiving confirmation that targets are destroyed. Whereas President Putin has made previous statements hinting at this concept, Basic Principles showcases its first appearance in an official public document.12

Western actions have undoubtedly motivated some of the changes in Russian nuclear posture, especially the U.S. withdrawal from the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in June 2002 and the more recent abrogation of the INF Treaty.13 Moscow may hope to discourage the return of intermediate-range ballistic missiles to Europe.14 Given the February 2020 deployment of low-yield W76-2 warheads on U.S. submarine-launched ballistic missiles, perhaps Russia also is directly addressing the “discrimination problem” between low- and high-yield warheads, clarifying that it will not wait to assess incoming damage before retaliating.15 (See “Tactical Nuclear Weapons are Back,” pp. 48–53, April 2018, and “Tactical Nuclear Weapons at Sea,” pp. 90–91, August 2020) On the other hand, this change could signal a desire to encourage the peaceful removal of these assets.

The Future of Arms Control

One major benefit of an explicit Russian nuclear strategy is the clarification it provides to guide future arms control. Paragraph 15 of Basic Principles restates Moscow’s commitment to maintaining nuclear forces “at the minimal level sufficient for implementing the tasks assigned.” In addition, paragraph 12 of Basic Principles calls for deterrence against “uncontrolled proliferation of nuclear weapons, their delivery means, technology and equipment for their manufacture”—similar to the 2018 NPR’s pledge for “verifiable, durable progress on non-proliferation.”

If analysts judge Basic Principles a sincere statement of Russian policy, the U.S. Navy should reconsider its deployment of the low-yield W76-2 warhead. First, the “launch on attack” posture nullifies the supposed flexibility in escalation provided by a 6.5-kiloton warhead (compared with the 90-kiloton W76-1). Second, the apparent repudiation of “escalate to de-escalate” implies Russia would not launch nuclear weapons to convince NATO to abandon the fight, whether against surface action groups and carrier strike groups at sea or battlefield ground forces on land. But such scenarios were the justification for the W76-2, as well as the research and development of intermediate-range, dual-capable, ground-launched missiles.16 If, however, U.S. military leaders believe Basic Principles should not be taken at face value, or they fear that, in a crisis, the escalate to de-escalate advocates might win the day, the best response for the Navy arguably is emerging high-precision technologies such as hypersonic vehicles to ensure variable-payload conventional or nuclear retaliation, rather than a low-yield nuclear weapon launched from a ballistic-missile submarine—with all the risk that entails. (See “Fast and Furiously Accurate,” pp. 14–18, July 2019).

An appropriate forum for discussing removal of the W76-2 warheads would be talks on the extension of the 2010 New START treaty, which is set to expire on 5 February 2021. Russia has offered an unconditional five-year extension, but formal dialogue on extension could expand to include some of the emerging technologies highlighted in paragraph 12.17 The Avangard nuclear-armed hypersonic glide vehicle and the nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed Poseidon torpedo do not fall under New START limits, but they and other platforms from Putin’s March 2018 State of the Federation Speech will challenge U.S. nuclear primacy.18

The gravest concern is the movement toward first use. Russian Presidential Press Secretary Dmitry Peskov has declared that Moscow will not employ nuclear weapons first, but three of the four potential conditions for use in paragraph 19 are not inherently nuclear threats, implying Russia could execute a first strike. The NPR implies the same of the United States. As a result, there is no clear path forward even for establishing confidence-building measures.

Unanswered Questions

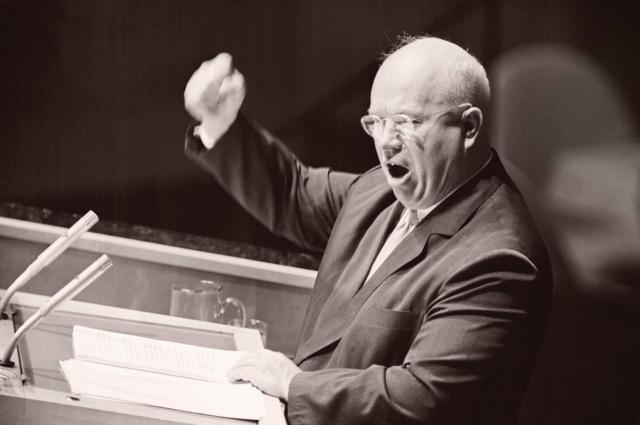

Even if arms control dialogue between the United States and Russia remains at a standstill, Basic Principles exemplifies the dynamism of Russia’s nuclear policy in recent years. Putin has made his mark as the most actively engaged Russian/Soviet leader on nuclear weapons since Nikita Khrushchev, but he has gone further than Khrushchev by preserving both the economy and his authority. While actively pushing for nuclear modernization and deterrence, Putin now uses Basic Principles to inform the world that any use of nuclear weapons will have been “compelled” on Russia.

But this first explicit public doctrine leaves unanswered questions about whom it touches, what it covers, and how it will be executed. Does Russia’s nuclear umbrella include the Collective Security Treaty Organization countries of Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan? While France, with its hypersonic, medium-range ASN4G cruise missile, and Germany, with its Heron TP unmanned aerial vehicle, are likely targets for Russia’s nuclear deterrence, does the document implicitly warn China to maintain a “strategic partnership” with Russia?19 While many threats are enumerated in paragraph 12, do radiological or nuclear terrorism warrant deterrence? If “launch on attack” applies only to ballistic missiles, what kind of warning is reliable, and do hypersonic missiles or a barrage of cruise missiles change that calculus? If Putin becomes incapacitated, how does command-and-control authority pass to the prime minister? Last, is there a secret version of the Basic Principles document that can answer these questions?

The challenges of conflict escalation in the new nuclear age will lead to what analysts like to call “wormhole dynamics”—less predictable escalation pathways, unpredictable advanced technologies, and the diffusion of global power.20 However, the clearer the foundation of a doctrine—such as Basic Principles—the clearer the path forward will be in this complex environment.

1. The President of the Russian Federation, Basic Principles of State Policy of the Russian Federation on Nuclear Forces, The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, 2 June 2020.

2. Nikolai Sokov, “Russia Clarifies Its Nuclear Deterrence Policy,” Vienna Center for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation, 3 June 2020.

3. President of the Russian Federation, The Military Doctrine of the Russian Federation, The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, 25 December 2014; President of the Russian Federation, National Security Strategy, The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, 31 December 2015.

4. Maxim Starchak, “Russia’s New Nuclear Strategy: Unanswered Questions,” Royal United Services Institute, 26 June 2020.

5. Hans Kristensen and Matt Korda, “Russian Nuclear Forces, 2020,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 76:2, 102–17, 9 March 2020.

6. Lori Esposito Murray, “What the INF Treaty’s Collapse Means for Nuclear Proliferation,” Council on Foreign Relations, 1 August 2019; Office of the Secretary of Defense, Nuclear Posture Review, February 2018.

7. Sokov, “Russia Clarifies.”

8. Cynthia Roberts, “Revelations about Russia’s Nuclear Deterrence Policy,” War on the Rocks, 19 June 2020.

9. Olga Oliker and Andrey Baklitskiy, “The Nuclear Posture Review and Russia ‘De-Escalation’: A Dangerous Solution to a Nonexistent Problem,” War on the Rocks, 20 February 2018.

10. Olga Oliker, “New Document Consolidates Russia’s Nuclear Policy in One Place,” Russia Matters, 3 June 2020.

11. Pavel Aksenov, “Stanislav Petrov: The Man Who May Have Saved the World,” BBC Russian, 26 September 2013.

12. “Meeting of the Valdai International Discussion Club,” President of Russia, 18 October 2018.

13. Wade Boese, “U.S. Withdraws from ABM Treaty; Global Response Muted,” Arms Control Today, July 2002.

14. Roberts, “Revelations about Russia’s Nuclear Deterrence Policy.”

15. Vipin Narang, “The Discrimination Problem: Why Putting Low-Yield Nuclear Weapons on Submarines Is So Dangerous,” War on the Rocks, 8 February 2018.

16. Sokov, “Russia Clarifies.”

17. Ankit Panda, “What’s in Russia’s New Nuclear Deterrence ‘Basic Principles’?” The Diplomat, 9 June 2020.

18. “Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly,” President of Russia, 1 March 2018.

19. Starchak, “Russia’s New Nuclear Strategy: Unanswered Questions.”

20. Rebecca Hersman, “Wormhole Escalation in the New Nuclear Age,” The Strategist, Summer 2020.