One fascinating way to determine the suitability of weapons and tactics is through wargaming. And modern, computer wargames can offer previously unseen levels of fidelity and accuracy over tabletop versions. One game in particular demonstrates how U.S. Navy ships could fare in action against their People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) counterparts.

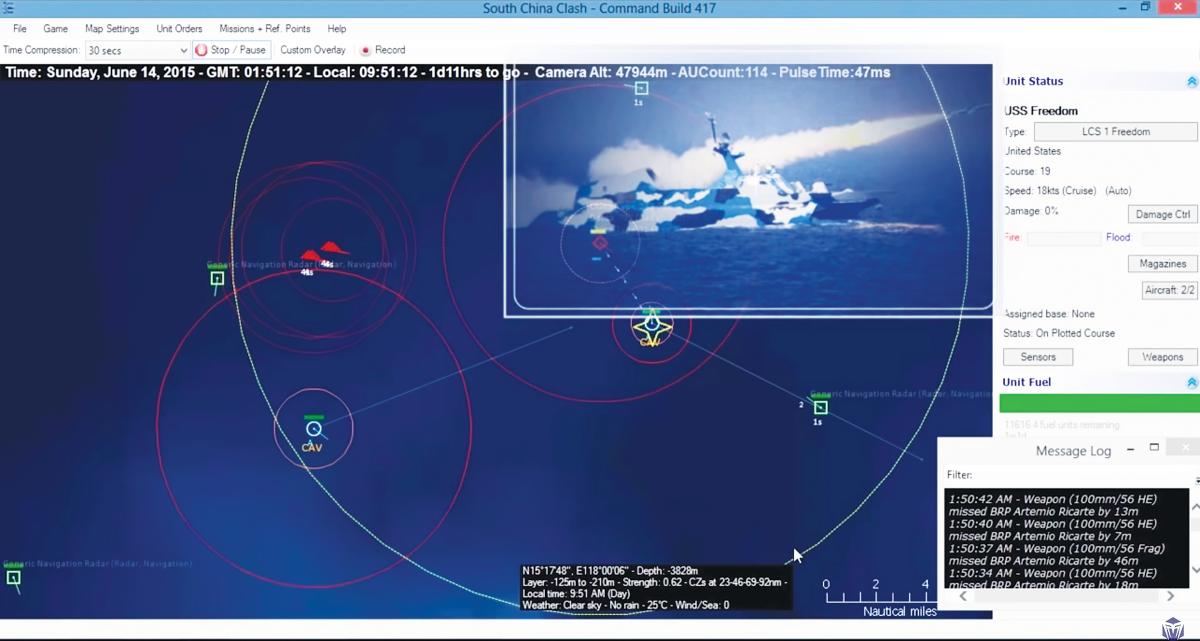

Command: Modern Operations (CMO) is a descendant of 2013’s Command: Modern Air/Naval Operations. CMO attempts high-fidelity simulation of air, sea, and (limited) ground operations, from the early Cold War era to today. It models the gamut of modern warfare, from submarines to ballistic-missile defense, using open-source information on capabilities, realistic physics, and accurate rules of engagement. The publisher, Matrix Games, also sells professional versions to the armed forces of several NATO countries.

The game includes many ready-made scenarios, including some that examine “What if?” scenarios from the past, present, or future. One of these plays out a clash between the Philippine Navy and the PLAN near Scarborough Shoal, which quickly draws in the U.S. Navy.

In 2013, shortly after the game’s release, I played this scenario (set in 2015), and wrote about it for War Is Boring. It ended in a defeat for the U.S. Navy, with two inadequately armed littoral combat ships (LCSs) sunk. But with the Navy beginning to upgun both LCS classes with the Raytheon-Kongsberg Naval Strike Missile (the USS Gabrielle Giffords [LCS-10] was the first to receive them, in 2019), it seemed worth refighting the scenario to see how the results might change.

The scenario description begins:

China . . . has begun to press longstanding maritime claims with the hopes of rolling back potential adversaries. . . . [Its] strategy [is] borne of the notion that the PLAN vastly outclasses most nations in the region and that the United States will never risk war or economic disaster over a small maritime claim. . . . Sparsely populated and of marginal value to the fishing industry, [Scarborough Shoal] is contested by the Philippines and [China, which] has begun . . . sending Coast Guard vessels along with its fishing fleet to protect its interests. With the U.S. forces on the not-so-distant horizon, the Philippine Navy may feel empowered to act.

The scenario was designed for a human player to control U.S. Navy forces against a computer-simulated China.

While Philippine and PLAN vessels face each other down, the U.S. Navy stations the Independence-class USS Manchester (LCS-14) and Charleston (LCS-18), each armed with eight Naval Strike Missiles (NSMs), some 30 miles south of the Philippine ships. (The 2013 version used the USS Freedom [LCS-1] and Fort Worth [LCS-3], because it predated the Navy’s decision to station the odd-numbered Freedom-class ships on the U.S. East Coast, and the even-numbered Independence class on the West Coast.) Each LCS also is equipped with two MQ-8B Fire Scout unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs).

Forty miles south is the USS McCampbell (DDG-85), a Flight IIA Arleigh Burke–class destroyer with two MH-60R Seahawks embarked. Halfway between the LCSs and Subic Bay is an MQ-4A Triton UAV, with two more 2,000 miles away at Guam’s Andersen Air Force Base. The U.S. commander’s subsurface asset is the Virginia-class attack submarine USS Hawaii (SSN-776). Manned fixed-wing assets exist in theater but did not participate as the scenario unfolded.

The Chinese forces consist of an older Type 053H Jianghu-class guided-missile frigate, now serving in the China Coast Guard as CG1002. A Chinese Navy task force, comprising one Type 052C guided-missile destroyer, two Type 054A Jiangkai II frigates, and a Type 056 corvette, is lurking somewhere to the north. Chinese submarines are known to be operating in the area. Flying from an air base on Woody Island in the South China Sea are J-10AH Vigorous Dragon multirole fighters, JH-7A Flounder strike aircraft, Ka-28 Helix A antisubmarine warfare helicopters, Y-8X Cub turboprop patrol aircraft, and Z-9C (Dauphin 2) helicopters. PLA theater ground assets consist of a signals intelligence station and YLC-2 radar.

The scenario directs the U.S. commander to “deploy forces at your disposal as required to monitor Chinese activity.” The 2013 simulation saw the two LCSs sucked into a surface action against the larger Chinese task force. The Freedom and Fort Worth, at the time equipped with the planned antisurface mission module that included 15 Griffin IIB short-range missiles each, were badly beaten by Chinese warships fielding powerful antiship cruise missiles (ASCMs). The Griffins and the MH-60Rs’ AGM-114 Hellfire missiles were considerably outranged by the PLAN’s YJ-83 ASCMs. When U.S. forces were finally able—at great cost—to close within Griffin range, they discovered that the 13-pound multi-effect warheads were far too small to do meaningful damage to the Chinese ships. And the LCSs’ defensive limitations meant both ships were inadequately equipped to defend against a concerted cruise-missile attack.

Context is important, though. In 2013, the surface warfare package for the LCS was optimized to defend against massed attacks by small craft employing infantry support weapons—essentially, the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps Navy’s concept of operations. Against unarmored speedboats armed with 12.7-mm heavy machine guns and 107-mm rocket launchers, the Griffin IIB missile is a reasonable weapon, as is the ship’s Mk 110 57-mm gun, with its high rate of fire. The Griffin’s small size enabled an LCS to carry a large number of missiles, a fair tradeoff against speedboats.

The People’s Liberation Army Navy, on the other hand, is far more lethal. It prefers more traditional surface combatants. During the 2010s, it rapidly equipped itself with such warships as the Type 056 corvette, Type 054A frigate, Type 052C and Type 052D guided-missile destroyers, and the Type 055 guided-missile cruiser. And it armed these warships with modern ASCMs. The YJ-83, for example, carries a 400-lb warhead; the newer YJ-18’s is more than 600 pounds.

The result of the updated scenario was dramatically different. Once the shooting started, the U.S. Navy player used its intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance assets—the MQ-4A Triton and MQ-8B Fire Scouts—to quickly pick the China Coast Guard ships out from nearby Chinese fishing trawlers and maintain a fix on the Type 056 and the Chinese surface task force. Electronic support measures on board the Manchester, Charleston, and McCampbell also played a role in isolating the PLAN ships.

Chinese missiles and guns quickly sank the Philippine ships. The Charleston suddenly came under attack by four ASCMs launched from the west, an area with no known Chinese surface contacts. Flying at 520 miles per hour and an altitude of 60 feet, these missiles fit the profile of YJ-82 (YJ-802Q) submarine-launched ASCMs. The Charleston’s RIM-116C Rolling Airframe Missiles knocked down three, while the fourth veered off course.

Now it was the U.S. Navy’s turn. The two LCSs each fired two-NSM volleys at the two closest Chinese warships, 30 to 35 miles away. Each PLAN ship was well within NSM range, and the LCSs did not need to sprint toward the enemy as one had in the 2013 version. The China Coast Guard vessel CG1002 was sunk by the first NSM to impact. The Type 056 corvette waiting nearby was also destroyed. The low-observable NSMs, flying at low altitude and capable of evasive maneuvers during the terminal phase of flight, evaded enemy defenses and slammed into their targets one after the other.

With the immediate surface threat eliminated, the Navy was free to deal with the subsurface and aerial threats. The McCampbell, with Aegis providing antiair overwatch for the two LCSs, knocked down a Y-8X patrol craft, a flight of JH-7A Flounders armed with antiship missiles, and a flight of J-10AH fighters. The Manchester suffered damage from one YJ-83A but remained afloat.

In 2013, the short engagement between the U.S. Navy and the PLAN/China Coast Guard was a disaster for the United States, with a corvette and an outdated frigate outfighting brand new LCSs. In 2019, swapping Naval Strike Missiles for Griffins was enough to turn the tide in the engagement early on, sinking the PLAN and China Coast Guard ships without U.S. losses. Had the Chinese surface task force closed with the U.S. ships, the remaining 12 NSMs would probably have been sufficient to sink the majority of the ships.

Using simulations to model real-world actions is fraught with pitfalls and caveats. However, a comparison of the two simulations’ outcomes suggests the corrective action taken to increase the firepower of the LCS fleet is a positive development. While the NSMs may not be as useful as Griffins (recently replaced by Hellfire missiles) against massed speedboat attacks, a deployment-based adjustment of missile loadouts—or a clear delineation of the geographical areas of responsibility for specific LCSs—would be an option.

More broadly, the simulation suggests that games such as CMO could be useful in modeling upgrades to existing ships, examining how a notional design might perform or how adversaries’ weapons could perform against U.S. and allied naval systems. While CMO and similar systems may not have the fidelity of military-grade simulations, informal or off-hour use might provide sparks of insight difficult to obtain by other means.

In 2013, I suggested the Naval Strike Missile deployed on LCSs could have dramatically altered the South China Sea scenario in favor of U.S. forces. Six years later, NSMs were deployed on an LCS in the South China Sea. While I am by no means suggesting these events were linked, it is interesting that the manner in which the scenario played out predicted the Navy’s later course of action. Are there other insights waiting to be discovered in computerized wargames? There is only one way to find out.