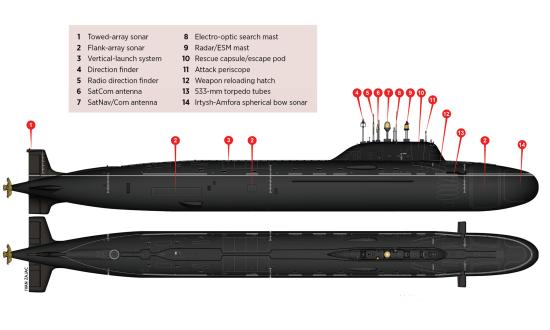

In 2014, the Russian Federation commissioned the cruise-missile submarine Severodvinsk. The Northern Fleet–based Severodvinsk made its first patrol into the Atlantic in the summer of 2018. It is extremely quiet and can travel at speeds up to 31 knots submerged and deploy weapons from ten torpedo tubes and eight vertical launching system (VLS) tubes, making it the most serious undersea threat to a U.S carrier strike group and the eastern half of the U.S. homeland in decades.1 Follow-on hulls of the class will be even more capable.

The Severodvinsk has considerably narrowed the U.S. undersea advantage. The increased threat makes clear that the Navy needs submarine officers who are not just good engineers able to manage a nuclear power plant, but who also are warriors who can lead the force in a high-end fight. In the new era of great power competition, the submarine force should emphasize warfighting over engineering in recruiting Naval Academy midshipmen.

The (Failed) Hunt for the Severodvinsk

In response to the Severodvinsk’s 2018 operations, the Navy deployed submarines, ships, and maritime patrol aircraft to hunt for the submarine. Vice Admiral Andrew L. Lewis, commander of the newly reestablished Second Fleet charged with defending the western Atlantic, said in an interview at the time, “The Atlantic Ocean is no longer a safe haven. Our new reality is that when our sailors toss the lines over and set sail, they can expect to be operating in a contested space once they leave Norfolk.”2

During the Cold War, the Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom (GIUK) gap was the vital chokepoint to monitor for Soviet submarines attempting to transit into Atlantic waters. The U.S. and allied undersea advantage and vast monitoring system ensured Soviet submarines rarely got through undetected. In 2018, the Severodvinsk proved that Russia’s most advanced submarines now challenge that chokepoint.

If the Navy cannot find a submarine off the U.S. coast, it must redouble its efforts to improve training, technology, and doctrine or risk losing its competitive edge in the undersea warfare domain. The loss of this advantage would not just imperil naval operations, but joint operations as well. Submarines provide the joint force with critical intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance and first strike capabilities.

During World War II, Admiral Chester Nimitz said, “It is to the everlasting honor and glory of our submarine personnel that they never failed us in our days of great peril.”3 Indeed, it was the submarine force that created the space that allowed U.S. industry to replace the ships lost at Pearl Harbor. Today’s submarine force is just as important and must be able to meet Nimitz’s standard for success. For this reason, the most capable submarine warfare junior officers today must be warfighters first and engineers second to meet this challenge.

Nuclear-Powered Submarines are Warships

It should be clear to every midshipman that U.S. nuclear reactor technology powers the world’s greatest warships, not the other way around—Navy ships do not exist to drive nuclear reactors around the world. Yet, there remains a widespread perception among midshipmen that the submarine community is rooted not in warfighting but rather in the caretaking of the nuclear reactor. That an officer can be both an engineer and a superb tactician is a concept to which many midshipmen do not subscribe. Phrases such as “procedural compliance” are misconstrued to mean little or no creativity is permitted and blind adherence to instruction is demanded.

The 2018 Commanders Intent for the United States Submarine Force dispels the notion that submarining is solely reactor- and engineering-focused, however. Throughout the document, reactors are mentioned only once; instead, it focuses on developing core operational capabilities in the areas of conflict deterrence, access with influence, intelligence collection, and, most important, warfighting. The engineering and technical nature of submarines is a means to an end, not an end in itself. Reaffirming the submarine force’s warfighting nature would foster a culture of responsibility and pride, attracting midshipmen to its challenges and rigors.

The Big Warfighting Picture

The submarine practicum classes at the Academy are too focused on watchstanding procedures, Nuclear Power School, and the daily routine of a division officer. This is monotonous, and midshipmen do not get a good sense of how these areas of instruction fit into the bigger war-

fighting picture. The why that future leaders seek is to know the impact they will make on their subordinates and in serving their country. Linking the daily routines of submarine life to the bigger picture of warfighting will bolster the submarine community’s appeal.

Admiral Hyman G. Rickover once said, “If a man feels he is only a temporary custodian, or that the job is just a stepping stone to a higher position, his actions will not take into account the long-term interests of the organization.”4 Midshipmen choosing submarines want the prestige of meaningful hardship that other communities, such as the SEALs or the Marine Corps, offer their potential selectees. The prospect of being primarily a nuclear power officer instead of an undersea warfighter does not do that.

Retaining the Best Warriors

Once midshipmen choose the submarine community, more of them need to make submarine warfare a career. According to a 2014 retention survey, 50 percent of submarine junior officers intended to resign immediately after their initial service obligation. Only 28 percent aimed to stay in for a career, and 56 percent believed that the operational tempo is too high. Finally, 89 percent believed it would be easy to find employment after they left the Navy.

Talented and trained officers cannot be easily replaced. The survey results, coupled with the new blended retirement system, signal that in the near future more midgrade officers will leave the service for lucrative opportunities. This will make it more difficult for the submarine force to meet its O-5 and O-6 requirements.

The Department of Defense relies on the submarine force to execute all its missions without fail, especially strategic deterrence. Attracting and retaining the best officer talent from the Naval Academy is a critical part of ensuring the emerging undersea warfare challenges to the United States can successfully be met. In selecting the submarine community, midshipmen must know that they are not entering a community of engineers, but one of warfighters who value first and foremost the dangerous and often uncelebrated work of the silent service.

1. Eric Wertheim, “Russia’s Capable New SSGN,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 146, no. 5 (May 2020), usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2020/may/russias-capable-new-ssgn.

2. John Gordon, “U.S. Submarines Scrambled to Find a Deadly New Russian Sub off the East Coast in Major Operation,” The Daily Mail, 6 February 2020, dailymail.co.uk/news/article-7972447/U-S-submarines-scrambleddeadly-new-Russian-sub-East-Coast-major-operation.html.

3. “December 7th, 1941: A Submarine Force Perspective,” 7 December 2016, usnhistory.navylive.dodlive.mil/2016/12/07/december-7th-1941-a-submarine-force-perspective/.

4. Admiral Hyman G. Rickover, 1982 Speech at Columbia University, govleaders.org/rickover.htm.