“Maritime skill is like skill of other kinds, not a thing to be cultivated by the way or at chance times; it is jealous of any other pursuit which distracts the mind for an instant from itself.”1

These words from Pericles’ address to the Athenaeum echo through our profession as mariners, particularly as mariners with a mission to conduct prompt and sustained combat operations at sea. What naval officers do is a blend of science and art, a juxtaposition of the rigid machine and the fluid, dynamic environment of the ocean, and it is a perishable skill.

Perishable skills must be revisited, refreshed, and renewed if one hopes to attain and then retain proficiency. Among the principle skills a mariner must have is the ability to navigate safely in restricted and open waterways, including negotiating maritime traffic. Today, our predominant reference is the 1972 Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, commonly referred to as the ColRegs or Rules of the Road.2

Surface warfare officers train to the Rules of the Road in Navy schoolhouses, from the Basic Division Officer Course all the way to the Major Command Course, where previous ship captains again are challenged to demonstrate fluency in the principles of safe navigation and collision avoidance. In between, we emphasize proficiency under the Surface Force Training and Readiness Manual, the basic training guidance for seamanship and navigation certifications for ships preparing for deployment.

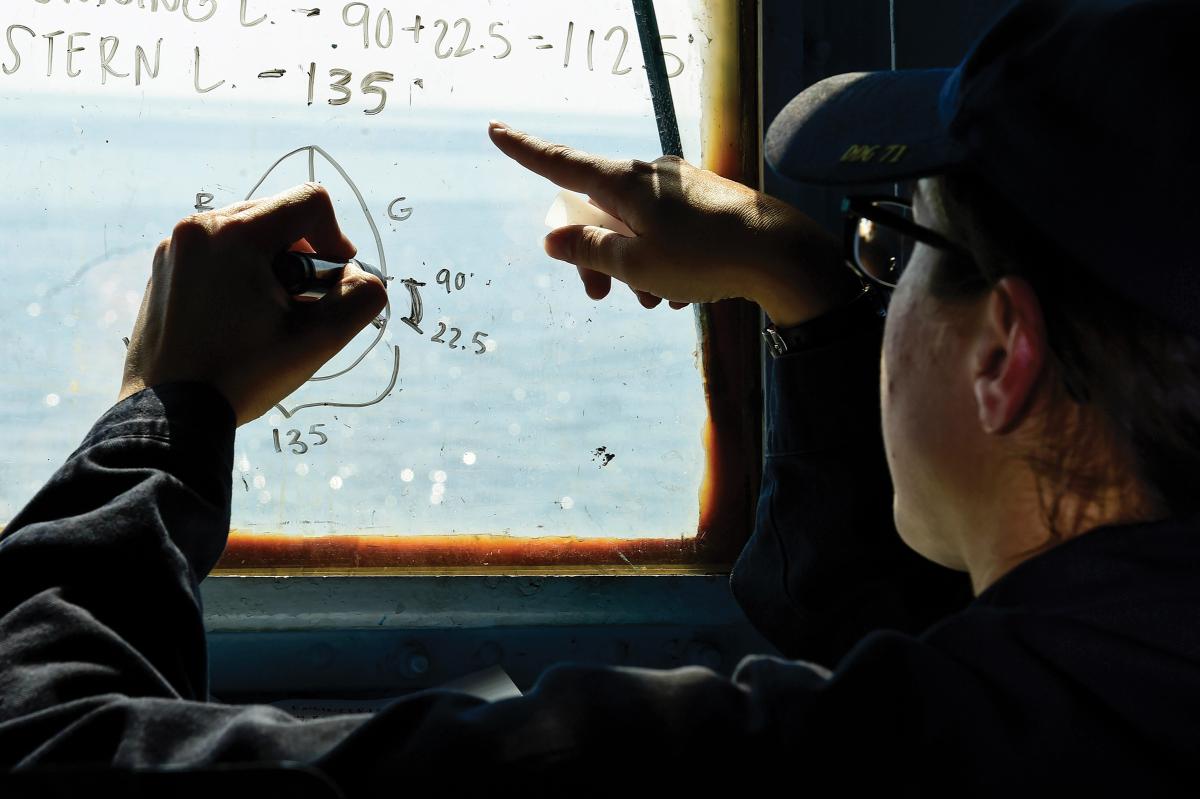

At the individual ship level we train and assess ourselves in navigation and surface contact management through the use of shiphandling simulators, individually and as bridge watch teams. Ships periodically test their deck officers and bridge teams on the Rules of the Road. Ship navigators administer these tests to wardrooms and ship control watchstanders, requiring minimum passing scores or remediation.

For a ship captain, everyone assumes the requisite level of knowledge is inherent in the person holding responsibility and accountability for the safety of the ship. Yet during my time at sea, there has been a presumption that taking the Rules of the Road exam is either a distraction for a sea captain or beneath the position, perhaps even an insult to suggest that someone granted authority to command a warship would need a graded assessment in something so fundamental.

Yet, for the same reasons cited by Thucydides, I willingly subordinate myself to my navigator’s call to the wardroom to take another monthly Rules of the Road exam: These mariner principles are critical and simultaneously perishable. Far be it from me to set the example for my deck officers that I do not need refreshing from time to time on the particulars of the regulations set forth for the safe conduct of ships on the high seas and inland waterways.

A newer emphasis also is in play for the captains of the current and future surface navy. As we seek a return to sea control and emphasis on distributed maritime operations, we will benefit from confident action in areas where maritime supremacy or even superiority cannot be assumed. Moreover, considering maritime operations in localized areas where electronic emissions control is preferred or electromagnetic spectrum usage is denied, we must be keenly aware of the regulations and guidelines for hazard-free travel on the seas.

For a stealth destroyer such as the USS Zumwalt (DDG-1000), this imperative is all the more acute, as the assumed circumstance for many of the ColRegs is when “two power driven vessels are in sight of one another.” A stealth destroyer is by design not looking to be in sight of another vessel, ever, if possible. And recent experience from my longer patrols at sea has demonstrated that even when I would prefer to be seen by another surface contact, either visually or by radar, I cannot count on the other ship having the same appreciation of our relative motion. The two-ship problem often becomes a single-ship solution to collision avoidance.

The stealth destroyer’s bridge team must know the governing rule sets cold, to be able not only to manage its own bridge contribution to a safe passage, but also to more clearly and quickly ascertain when the other bridge team is not acting according to the rules. What used to be viewed as an errant mariner not abiding by the ColRegs often is a mariner who is unaware of the risk of collision because he is unable to see the stealthily operating ship.

Don’t fear your Rules of the Road proficiency exams, captain. Line up with your deck officers and take your navigator’s proctoring with enthusiasm. If you come up short, regain your proficiency in the same manner as your newest officer of the deck—by studying. It is far better to identify and eliminate your knowledge gaps in the safety of your wardroom, surrounded by professional mariners from your own team, than to demonstrate how perishable are our mariner skills out on the open seas, where the risks are real and the consequences much more humbling.

As Pericles forewarns, “their want of practice will make them unskillful, and their want of skill timid.”3 Our profession requires mastery of the marine trade, and our mastery begets the proficiency and confidence our sailors deserve.

1. Thucydides, vol. 1, trans. B. Jowett (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1881), 91.

2. Department of Homeland Security and U.S. Coast Guard, Navigation Rules & Regulations Handbook (Paradise Cay Publications, 2015), i.

3. Thucydides.