In a 2019 memorandum announcing an interim force structure assessment, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Michael Gilday and Marine Corps Commandant General David Berger emphasized the importance of Navy–Marine Corps integration: “Naval integration is the cornerstone of our future naval force, and the challenges facing our nation demand that we fully leverage the strengths of both naval services.”1 In his planning guidance, General Berger declares naval integration imperative to enabling sea control and sea denial operations, capabilities critical to maintaining U.S. global forward presence in an increasingly contested maritime domain.2

Such calls are not new: A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower and Marine Corps Operating Concept: How an Expeditionary Force Operates in the 21st Century (MOC) both state the need for greater integration, and Navy and Marine Corps joint operating concepts, such as expeditionary advanced base operations and littoral operations in a contested environment, are predicated on it.

But while naval integration remains a priority for the Navy and Marine Corps, it has yet to be reflected in their professional military education (PME) programs. The Education for Seapower (E4S) study found there is little collaboration among the services’ academic institutions and only marginal attendance at each other’s schools.3 Attempts to create a truly integrated naval team will wither unless this issue is corrected.

Why PME?

Integration both at sea and ashore is critical to address a number of challenges, including antiaccess/area denial threats from rising powers such as Russia and China. To maintain their ability to project power at sea, the Navy and Marine Corps need to aggressively experiment with nontraditional command-and-control relationships, organizational structures, and emerging technologies that capitalize on both services’ unique strengths. They must cure the pathology of addressing problems in a solely service-centric way, and that requires developing sailors and Marines who understand how the other service thinks—its operating concepts, service history, and culture.

PME programs are ideal for this. The classroom is an incubator for ideas that drive innovation. It creates an environment where students can challenge conventional wisdom, gather with their counterparts in different services to share their experiences, and experiment with new and emerging operating concepts unconstrained by the limitations of operations or training.

Operational commands have often relied on the schoolhouses to help develop new tactics, techniques, and procedures for implementing emerging technologies. The Naval War College, for example, played a significant role in innovating carrier aviation, as did the Marine Corps schools in the development of the maneuver warfare doctrine.4

Today, the Navy and Marine Corps would benefit by greater integration in their PME programs. Over time, the operating forces would begin to see sailors and Marines better able to communicate the strengths and limitations of their own and the other service, effectively employ each service’s unique capabilities, and operate as an integrated team. However, this can be realized only if the services take a hard look at how they assign and allocate students and faculty.

The Current State

There is an alarming negative trend in cross-service attendance at PME programs. According to the E4S study, in 2016, 2017, and 2018, Navy officers represented only 8.62, 8.57, and 4.27 percent, respectively, of the total student population at the Marine Corps Command and Staff College. The statistics for Marine Corps University (MCU) are more sobering still: in 2018, of the 511 students enrolled in resident programs, just 13—2.5 percent—were Navy officers, significantly less than the 12.5 percent share MCU allocates.5

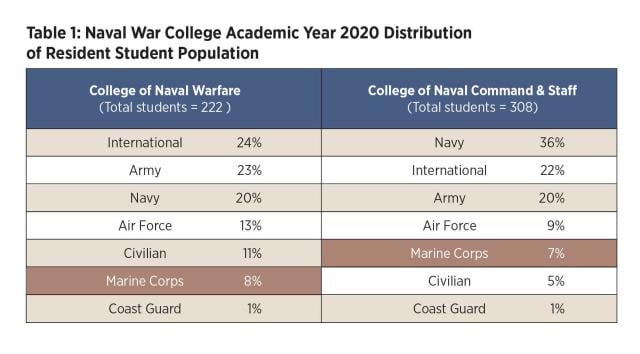

There is a similar lack of Marine Corps representation at the Naval War College (NWC). In academic year 2020, Marine officers constituted only 7 percent of the student population (21 of 308 students) at the College of Naval Command and Staff and just 8 percent (18 of 222 students) at the College of Naval Warfare—the smallest percentage among all the services.6 (See Table 1.)

The problem of mutual representation is not limited to the student population: Navy officers also are underrepresented on the MCU faculty. A review of MCU’s faculty directory shows four Navy officers on staff, with only one appearing to have teaching responsibilities.7 This lack of representation across services has a significant effect on the student experience. As Brigadier General William Bowers, former commanding general, Education Command, and MCU president, states in his response to the E4S study:

MCU students benefit greatly from the presence of sister service reps in the classroom and among the faculty. Unfortunately, USN students and faculty have been inadequately represented for many years. The shortcoming deprives our students of invaluable joint and maritime perspectives, and sends (at best) a very mixed message about how the DoN values education. At a minimum, every school should have one high-quality U.S. Naval Officer on its faculty, and one high-quality U.S. Naval Officer in each seminar room.8

General Berger also noted in his planning guidance that, “as a service, we lack the requisite naval education to engage our fellow naval officers and peers constructively in discussion on naval concepts, naval programs, or naval warfare.”9 Historical PME attendance rates are inadequate to achieve the level of naval integration desired by the service chiefs and necessitated by the current operating environment.

A Way Forward

Any efforts at reform must begin with a detailed analysis of student attendance and faculty assignments across the naval education enterprise. Such analysis must recognize that the services’ personnel management systems are geared toward number-centric solutions rather than a more decentralized model that would allow the operational commands and schools to identify the best potential students and faculty.10

Until detailed analysis has been completed, both services should increase the number of students they allot to attend the other’s PME programs. For example, for academic year 2021, the Marine Corps could reduce the number of lieutenant colonels it allocates to attend the Army War College and Eisenhower School and reallocate them to the College of Naval Warfare. The Navy could send an equivalent number of officers to the Marine Corps War College. This balancing would avoid net increases while making student integration a priority.

In addition, to ensure high-caliber officers serve as military faculty, both services should designate these positions at MCU and the NWC as priority assignments, selecting officers with demonstrated operational and academic achievement, potential for future leadership positions, and teaching ability.11 Military faculty billets are critical elements in the successful development of the Navy–Marine Corps team, and the services should elevate the prestige of these positions to a level just below command billets.

Having a balanced nucleus of Navy and Marine Corps military faculty composed of some of the brightest and most experienced officers across the naval education enterprise would provide priceless knowledge and expertise to the future leaders of the Navy–Marine Corps team.

For too long, the Navy and Marine Corps both believed they could accomplish their missions with little support from the other. The greater emphasis on naval integration today is not simply a matter of increasing goodwill but an operational imperative that may determine the success or failure of the nation in a future maritime conflict. Improving academic integration—to develop Marines and sailors with knowledge of the other service’s capabilities, operating concepts, and cultures—is a first step toward achieving the Navy–Marine Corps team the nation expects and needs.

1. ADM Michael Gilday, USN, and GEN David Berger, USMC, “Integrated Naval Force Structure Assessment,” joint memorandum, 6 September 2019.

2. General David H. Berger, USMC, Commandant’s Planning Guidance (Washington, DC: Headquarters Marine Corps, 16 July 2019), 2.

3. Education for Seapower (Washington, DC: Department of Navy, 19 April 2018), 47.

4. Jan M. Van Tol, “Military Innovation and Carrier Aviation—The Relevant History,” Joint Force Quarterly, no. 16 (August 1997): 77–87.

5. Education for Seapower, 45, 263.

6. “Naval War College Fast Facts,” NWC Public Affairs Office, 7 August 2019.

7. “Marine Corps University Faculty and Staff Directory,” as of October 2019.

8. Education for Seapower, 264.

9. Berger, Commandant’s Planning Guidance, 17.

10. Mie Augier, Sean F. X. Barrett, and Nicholas Dew, “Skills for Seapower: Why the Navy Needs to Teach Soft and Hard Skills,” Center for International Maritime Security, 4 November 2019.

11. Joint Chiefs of Staff, “Officer Professional Military Education Policy,” CJCSI 1800.01E (2015), B-2.