Navy officers are introduced to operational art too late in their careers. This is a missed opportunity and means the Navy is not using all available tools to win the next war.

Operational art is the “theory and practice of planning, preparing, and executing major naval operations aimed at accomplishing operational objectives.”1 It is the bridge between maritime strategy and naval tactics, providing a framework to prioritize and sequence tactical actions to attain operational and strategic objectives at sea. It includes an examination of the operational environment and the factors of time, space, and force, against which the supporting functions of logistics, fires, intelligence, command and control, and protection are applied. Operational art also involves identifying a center of gravity to attack either directly or indirectly to achieve a naval objective.

Operational art should not be learned for the first time as a mid-grade or senior officer. It should be studied throughout a career to allow for internalization of its concepts, development of associated critical thinking skills, and intellectual reflection to consolidate theory into practice.

U.S. Army officers learn and apply operational art much earlier in their careers than Navy officers. At their commissioning source, cadets are introduced to basic ground tactics, tactical planning, and order writing, which lays the foundation for the application of operational art concepts. During their junior officer assignments, they apply the functions of logistics, fires, maneuver, and command and control to execute tactical operations supporting operational objectives. As captains, armor and infantry officers attend the Maneuver Captains Career Course, where they build on and refine their operational art knowledge.

At the Naval War College, Army officers are highly sought during the joint military operations trimester because of their working knowledge and experience in operational art. The preponderance of Navy officers in the same seminars are learning operational art for the first time.

Navy junior officer training in the surface, submarine, and aviation communities is focused on mastering operation of the respective platform. Operational art and naval planning are not substantive parts of career milestone courses. Unless Navy officers attend a course dedicated to naval planning, they learn operational art concepts on the job.

There are multiple ways to establish operational art as part of the Navy ethos. One solution is to incorporate training in accession and milestone programs, such as the Basic Division Officer, Advanced Division Officer, and Department Head courses. These courses necessarily focus on operating and fighting the ship, but adding operational art could show how naval tactical actions link to sea control and provide an opportunity to examine how the Navy will fight today and in the near future. Armed with this knowledge, division officers and department heads can assist their commanding officers in developing concepts of operation to execute tactical actions in support of operational objectives—just as their Army counterparts do.

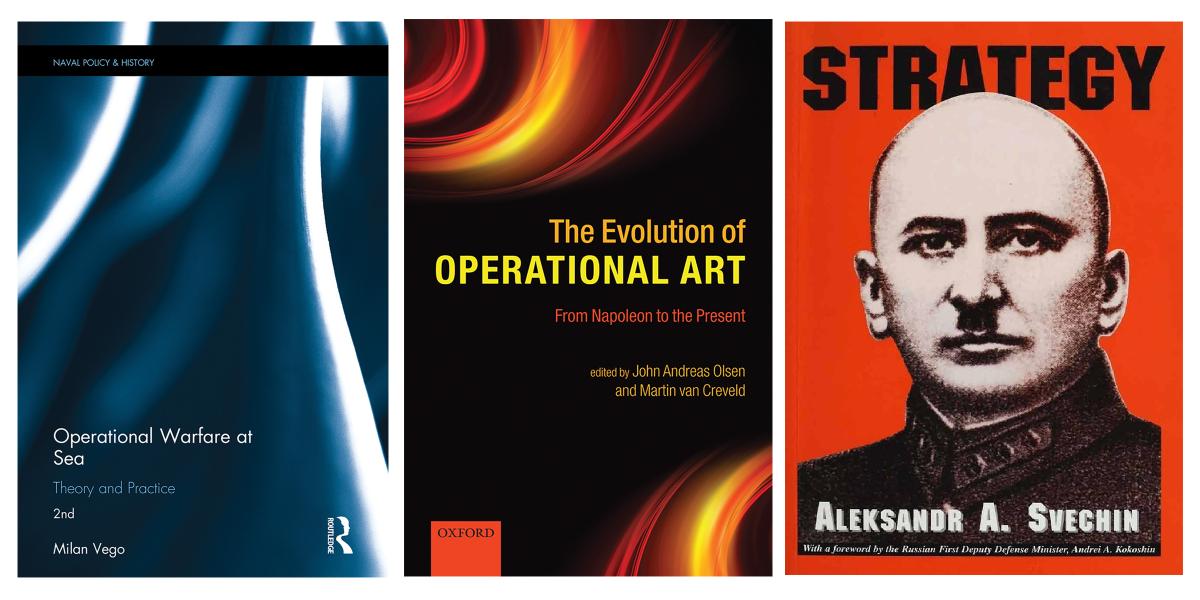

Sending Navy officers to resident professional military education institutions to learn operational art must continue. At the Naval War College, it is taught from the maritime perspective and delves into theory applied against case studies. But perhaps the best way to inculcate operational art is a grassroots approach—that is, for Navy officers to pick up a book to read about it. Reading is a beginning from which discourse can emerge in a wardroom and hopefully evolve into wardroom training. Milan Vego’s Operational Warfare at Sea is an excellent source for the theoretical foundations of operational art. Martin van Creveld’s edited anthology The Evolution of Operational Art: From Napoleon to the Present and Aleksandr A. Svechin’s Strategy both provide historical background and context. Any Navy officer would do well to be familiar with these works as he or she learns to apply operational art to maritime warfare.

The Navy needs strong thinkers at the operational level of war, leading to senior officers ready to cope with the rigorous intellectual environment of strategic leadership as warfare commanders and beyond. This is particularly true today, when the Navy, once again, has entered an era of peer competition and contested sea space.

1. Milan Vego, Operational Warfare at Sea: Theory and Practice (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2017), 1.