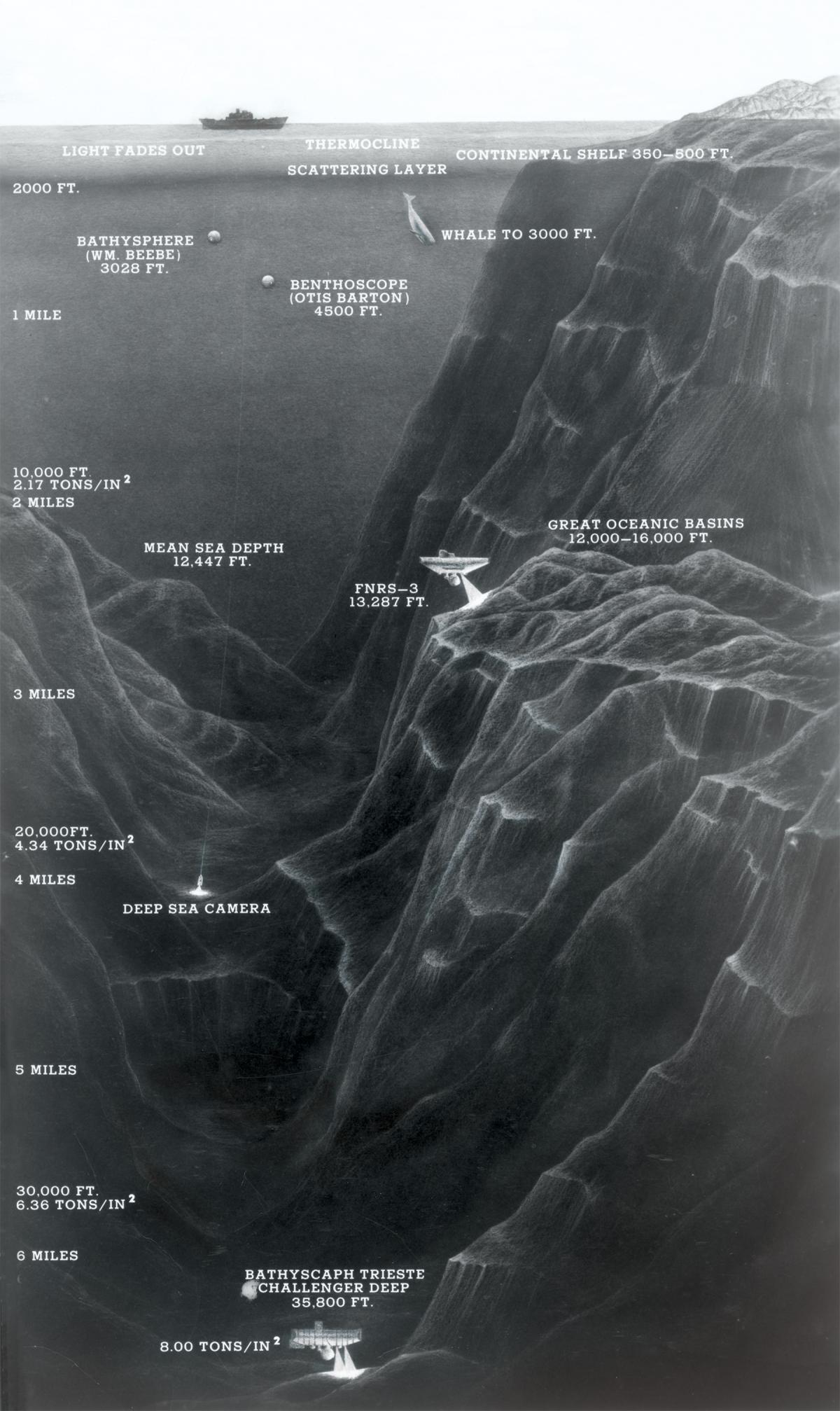

Fifty-one years ago, three Americans left Earth and reached the moon. Worldwide media provided extensive, minute-by-minute coverage of that historic event. Almost a decade earlier, on 23 January 1960, two men reached Earth’s deepest point: the Challenger Deep of the Mariana Trench in the western Pacific. There was relatively little media coverage of that historic event.

Acquiring the Trieste

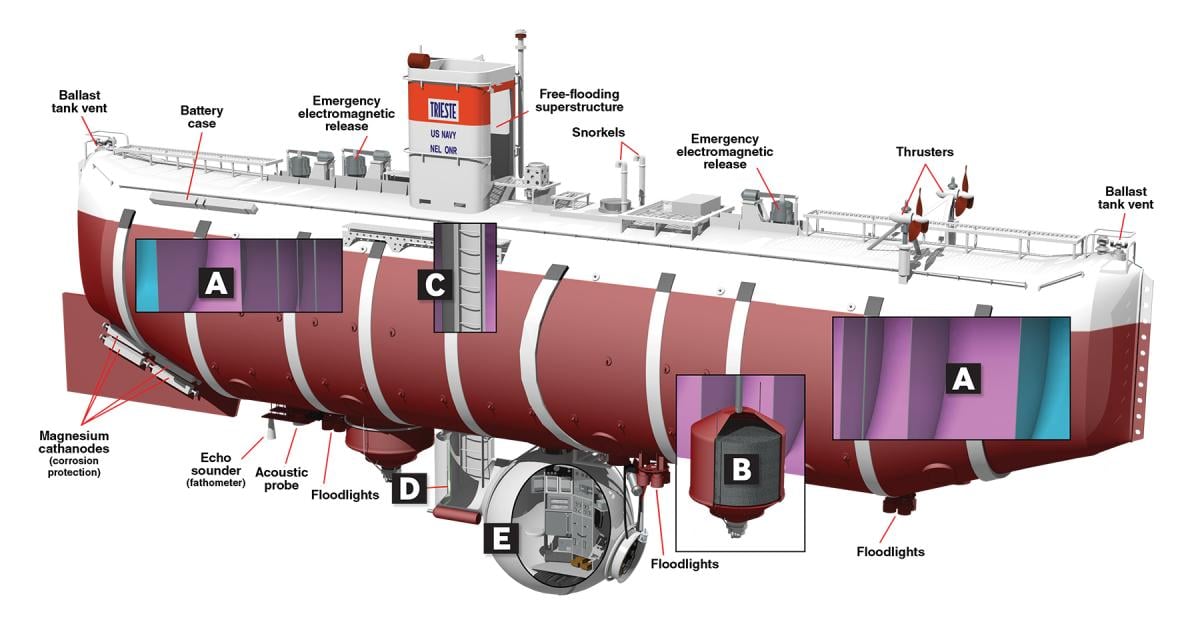

The U.S. Navy bathyscaph Trieste—carrying Swiss engineer Jacques Piccard and U.S. Navy Lieutenant Don Walsh—reached a record depth of 35,797 feet. The Trieste was designed and constructed by Jacques Piccard and his father, Auguste, in Italy and acquired by the U.S. Navy in 1958. The U.S. Office of Naval Research (ONR) purchased the bathyscaph, which, at the time, had a 20,000-foot diving capability and could provide access to 98 percent of the ocean floor. In addition, ONR had contracted with the Piccards to construct a second pressure sphere for the Trieste that could reach 36,000 feet.

The Trieste and its two spheres were shipped to the United States and assigned to the Navy Electronics Laboratory at San Diego. After assembly, testing, and training dives, the Trieste was shipped to Guam, some 190 miles northeast of the Challenger Deep. Towed from the naval base at Guam by a fleet tug and supported by the USS Lewis (DE-535), the Trieste reached the dive spot in mid-January. Piccard would pilot the “deep dive,” with the officer in charge of the Trieste, Lieutenant Don Walsh, logging the dive and maintaining communications with the surface.

Inauspicious Dive Conditions

Sunrise on 23 January 1960 found the sky overcast, the weather hot and humid, and the seas heavy with 25-foot swells. Piccard recorded:

Conditions didn’t look auspicious. Should everything be risked under these circumstances? . . . The sight that met my eyes when we boarded the wallowing bathyscaph was discouraging, to say the least. Broaching seas smothered her. The deck was a mess. Everything was awash. It was apparent that the tow from Guam had taken a terrific toll.1

When Lieutenant Walsh scrambled on board the Trieste, he too did not like what he saw: “What do you think, Jacques?” Piccard tested the electrical systems and the electromagnets, the latter to control ballast release. All circuits were in order. “I made the decision. We would dive.”2

Giuseppe Buono, the Trieste’s topside engineer, who had been with the Piccards for many years, followed Piccard and Walsh through the access trunk in the aviation gasoline (avgas)-filled buoyancy float into the sphere. All three men—Buono from outside, Piccard and Walsh from inside—lowered the 350-pound hatch into place and tightened the bolts. As he climbed out of the entry tube, Buono secured a one-of-a-kind watch to the ladder. The watch had been specially made for the dive by Rolex and kept hidden from Navy officials, who would have forbidden commercial use of a Navy activity.

On board the nearby destroyer escort Lewis a drama was in progress. The project leader, Andy Rechnitzer, received a message from the Navy Electronics Laboratory stating: “Cancel Diving. Come Home.” Rechnitzer took his time in responding. When he finally sauntered into the Lewis’s radio shack he could truthfully reply to San Diego, “Trieste now passing 20,000 feet.” It was a potentially career-destroying decision.

The Trieste had submerged at 0823, and at 80 feet nearly all of the surface wave motion was left behind. As the bathyscaph exited the noisy surface layer, communication by underwater telephone became possible. Both the Lewis and the Navy tug USS Wandank (ATA-204) had UQC underwater acoustic telephones.

The first stop on this “elevator ride” was the thermocline, a depth just below the point that wave action mixes warm surface water with deeper cool water. The rough sea conditions and internal waves had mixed the surface water to deeper levels, and there seemed to be four separate thermoclines: at 340 feet, 370 feet, 420 feet, and 515 feet. It took more than 30 minutes to penetrate them. Each layer required a release of the avgas, thus, when the last layer was breached, the bathyscaph was “heavy” and gradually picked up speed to almost three feet per second. At that rate, the ocean floor was more than three hours straight down.

Inside the Sphere

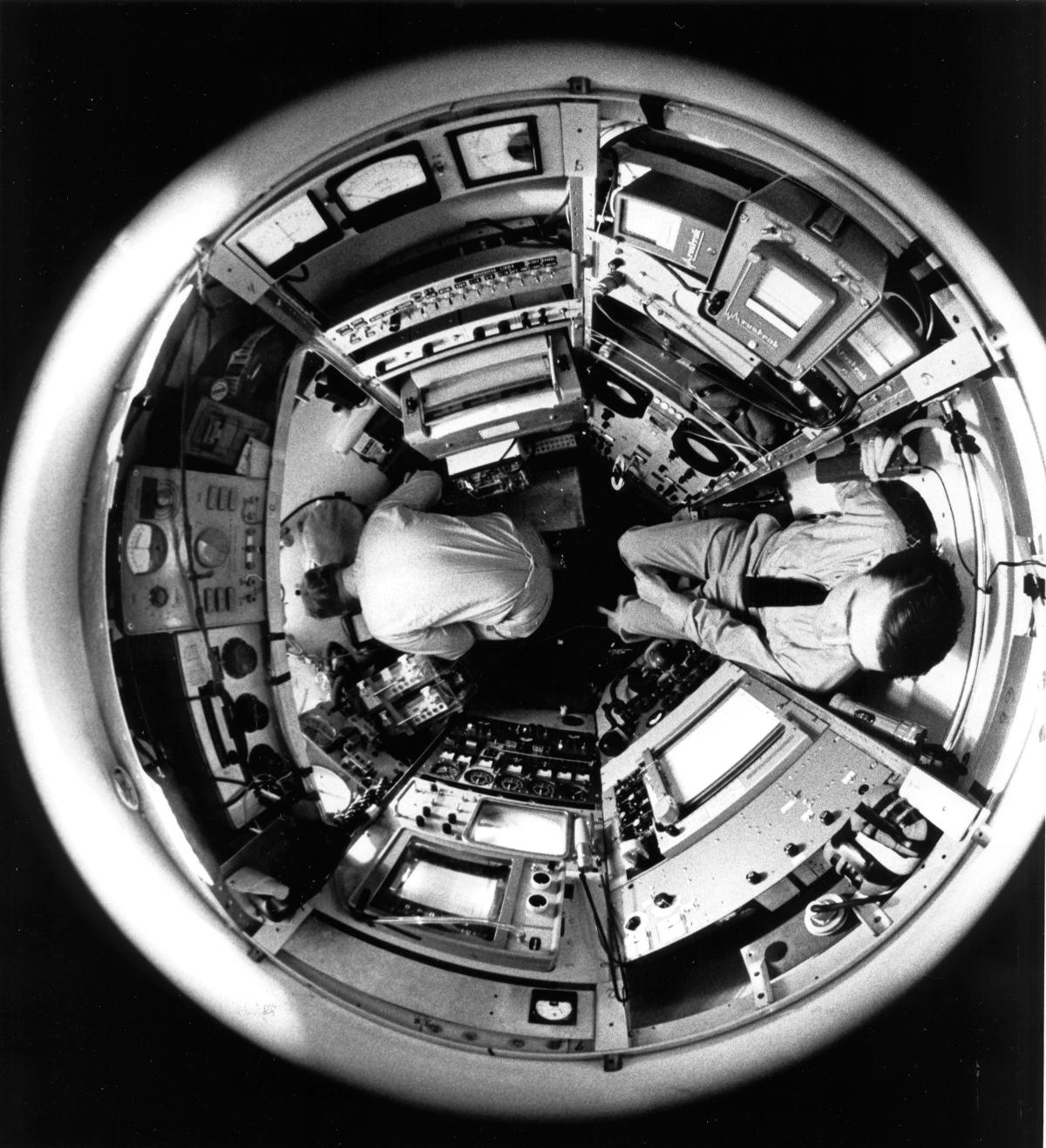

It was starting to cool within the sphere, and the two hydronauts changed into dry, warm clothing. Walsh explained, “It is quite an operation to see—two grown men changing clothes in a space 38 inches square and only five feet, eight inches high.”3 Walsh was dictating a running commentary into a recorder throughout the dive.

A small leak had started at about 10,000 feet through one of the stuffing tubes that brought electrical wires into the sphere. As they passed through 15,000 feet that leak began to seal, but another one began at about 18,000 feet and the inflow of water increased as they went deeper. The second leak also stopped as they continued to descend. Walsh and Piccard made note of the passing of 18,150 feet, a Trieste record set by Piccard and Rechnitzer on 15 November 1959, and of the passing of the 23,070-foot depth record set by themselves just 15 days previously.

They were aware that they were diving into a “hole” perhaps only one mile wide, with no knowledge of the character or proximity of the walls on either side of that hole.

At 27,000 feet, Piccard dumped enough ballast to slow to about two feet per second. Approaching 32,400 feet they felt a strong shock and a mild/muffled noise. “The sphere rocked as though we were on land and going through a mild earthquake.”4 Concern was immediate. Walsh recalled: “We waited anxiously for what might happen next. Nothing did. We turned off the instruments and the underwater telephone so that we could hear better. Still nothing.”5 Piccard and Walsh locked eyes; both men shrugged and without formal discussion continued the dive.

Approaching the Bottom

At 30,000 feet Piccard dumped ballast and slowed descent to about one foot per second. At 33,000 feet the fathometer was blank—“no bottom.” Slowly they descended, and at 36,000 feet Piccard joked: “Do you think we missed the floor?” Walsh replied in his characteristic, dry manner, “Probably not.”

Piccard dumped more ballast to slow to one-half foot per second. They drifted downward through 36,000 feet, then through 37,000 feet.

At 1256 the fathometer started, indicating bottom at 37,500 feet. They turned on the exterior lights. Piccard was watching out the forward window, while Walsh called out fathometer range to the bottom in fathoms: “Thirty . . . twenty . . . ten.” At an “altitude” of eight feet they sighted the bottom.6 There were no historic words spoken. This was an epochal event, observed within the Trieste sphere with a moment of silence and personal introspection.

Piccard reported seeing a fleet of medusae—small jellyfish-like creatures—at 2,100 feet above the bottom.7 Just prior to “landing” he reported a fish browsing in the silt, a flatfish—Piccard called it a sole—with both eyes on one side, about a foot long and six inches wide, white or silver in color. (Subsequent visits to such depths by both manned and remotely controlled vehicles have failed to corroborate Piccard’s sighting of fish inhabiting the Earth’s greatest depths. It is now widely accepted that the “fish” sighting was an error. Still, two other sightings of inhabitants—a shrimp and a fleet of medusae—proved that the ocean’s deepest depths do contain complex life forms.)

The Trieste quietly hovered a few feet above the muddy bottom at 37,800 feet, as recorded by the Trieste’s depth gauge, which turned out to be incorrectly calibrated. The corrected depth has since been rendered precisely as 35,797 feet. With no expectation of being heard, Walsh keyed his UQC underwater telephone: “Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, this is Trieste, we are on the bottom of the Challenger Deep at six-three hundred fathoms. Over.” (Pittsburgh was the communications call-sign of the Wandank). To their astonishment a reply came 30 seconds later: “Trieste, Trieste, this is Pittsburgh. I hear you faint but clear.”8 Piccard and Walsh could hear the excitement in the voice of Walsh’s assistant officer in charge, Lieutenant Larry Shumaker, on board the Wandank.

Walsh, looking out the rear window of the sphere, discovered the source of the unexplained vibrations at 32,400 feet. “I know what happened, that noise, that jolt,” he said quietly. “It was the big viewing port of the entry tube that cracked.” The crack was due to a shift of the metal structure, not due to pressure, as the entry tube was free flooded during a dive.

If the entry window failed and they were unable to blow the water out upon surfacing they would be trapped in the sphere until the Trieste was towed to Guam (four days), defueled, and lifted from the water. Auguste Piccard had designed the bathyscaph for such an eventuality, with snorkels that would provide fresh air during an entrapment.

The Trieste’s Ascent

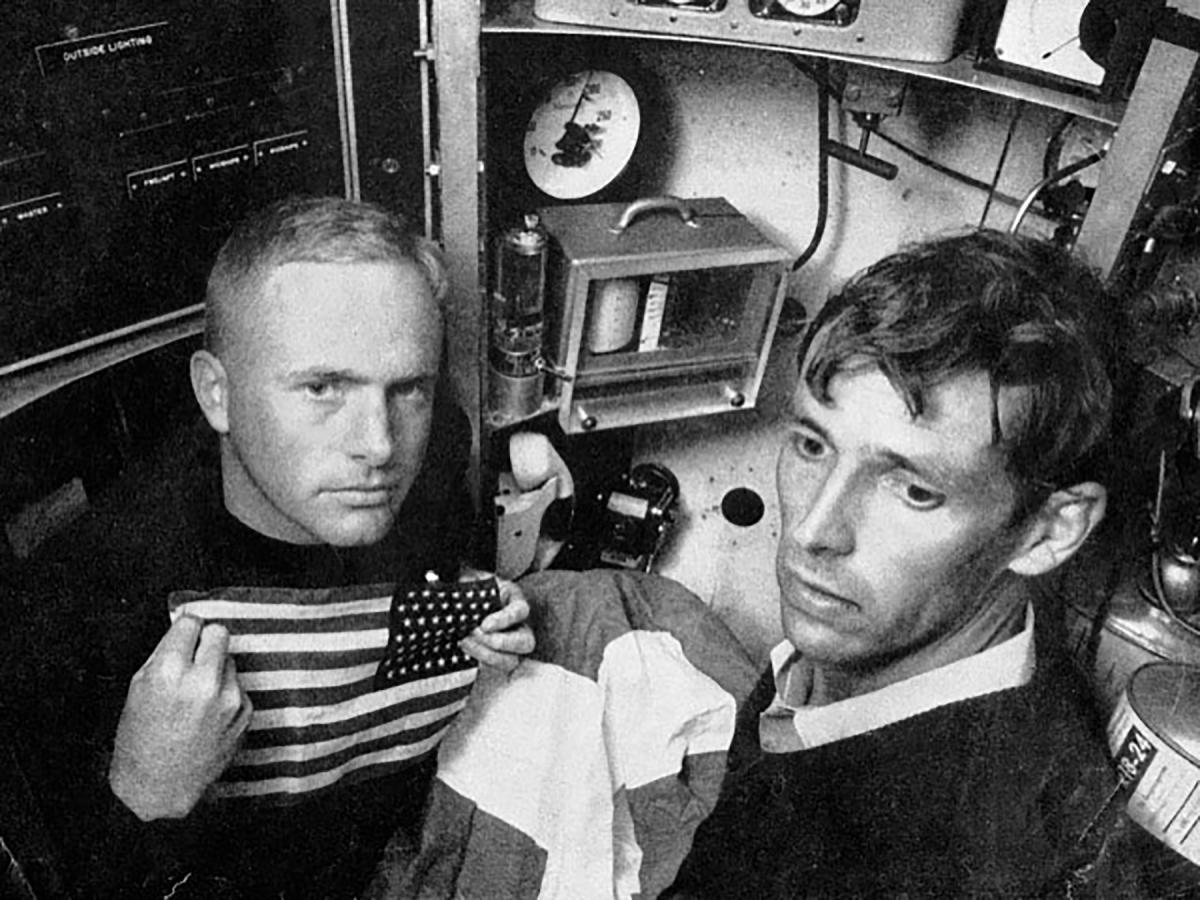

Now there was good reason to get to the surface as early as possible, to have maximum daylight to investigate the access trunk window problem. Before departing the bottom, the hydronauts shook hands, and displayed both a Swiss flag, for Piccard, and an American flag, for Walsh. They took pictures of their mini-ceremony with a fixed camera installed in the sphere.

After 20 minutes on the ocean floor, Piccard dropped two tons of ballast to start the ascent, while Walsh sounded six tones on the UQC. They were on an express elevator to the surface—three hours, 27 minutes at nearly three feet per second (or two miles per hour). They had a feeling of anticlimax, and then the cold hit both of them, hard. They had been in a small, damp sphere for more than five hours with an inside temperature about 45 degrees Fahrenheit. They reached for chocolate—each consuming a couple of bars. That was the only food they carried.

The Trieste broached the surface at 1656. Once on the surface the “trick” was to blow the water from the entry tube with the least possible stress to the acrylic window to prevent the crack from shattering and making exit from the sphere impossible. Walsh bled pressurized air into the access trunk very slowly. Finally, as the third bottle bled into the entry, the water level dropped past the viewport and a stream of air bubbles broke through the airline, indicating the entry tube was clear.

The pair lost no time exiting the sphere, slowing only to seal the hatch behind them. They climbed onto the Trieste’s deck, teeth chattering from hours in the chilled sphere, just as two Navy jet aircraft blasted by a few feet overhead, and into what seemed to be a carnival!

The Lewis had launched a rubber raft with two press photographers who took photos of Piccard and Walsh when they emerged. A second rubber raft was launched from the Wandank to pick up Piccard and Walsh and ferry them to the Lewis. Once on board the destroyer escort, they stood for photos and interviews with newsreel motion-picture coverage recording the event. The Lewis raced for Apra Harbor, arriving at 0800 on 24 January 1960, so reporters could file their stories as soon as possible. The Wandank, with the Trieste in tow, delayed by the heavy seas, did not arrive until 1000 on 28 January.

Subsequently, Walsh and Shumaker were awarded Navy medals by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Piccard and Rechnitzer received civilian awards from the President.

A Place in History

The Trieste, rehabilitated and fitted with the 20,000-foot sphere, went on to examine the remains of the sunken submarine Thresher (SSN-593) in 1963. Then, completely rebuilt, the Trieste II examined the Thresher wreck in 1964. In 1968, a third newly built bathyscaph labeled Trieste II (DSV-1), examined the remains of the sunken submarine Scorpion (SSN-589), helped recover aircraft from the ocean floor as well as errant satellite packages, and performed additional, highly classified missions. The “third” Trieste was retired in 1984.

The Trieste’s record dive of 35,797 feet went unchallenged for more than 50 years. In 2012 it withstood the attempt of James Cameron’s submersible Deepsea Challenger’s solo dive into the Challenger Deep, which was recorded at 35,787 feet. In April 2019, Victor Vescovo’s Limiting Factor submersible finally exceeded the Trieste’s record depth with three dives into the Challenger Deep over a five-day period, attaining 35,843 feet.

But the U.S. Navy’s bathyscaph Trieste was the first.

1. Jacques Piccard and Robert S. Dietz, Seven Miles Down: The Story of the Bathyscaphe Trieste (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1961), 161–62.

2. Piccard and Dietz, Seven Miles Down, 163.

3. Don Walsh, “Our 7-Mile Dive to Bottom,” Life, 15 February 1960.

4. Walsh, “Our 7-Mile Dive to Bottom.”

5. Walsh.

6. Walsh.

7. Don Walsh, “Dive #70 by the Bathyscaph Trieste,” acoustic recording transcript, 11.

8. Heinfield Voss, Krupp historian, email to Lee Mathers, 28 August 2013.