You work in an industry that is critical to national security. You endure difficult working conditions, long days, and shift work. You know that some former employees suffer from maladies that may be related to the work environment, the same one in which you toil each day. Your leaders know the consequences of this health epidemic, but they also are aware of the exorbitant cost and operational impact of addressing the issue and implementing mitigations that would ensure the well-being of the workforce long after workers leave the company. You are:

1. A coal miner in 1960.

2. A navy sailor in 2020.

Answer: Both. Fatigue is the Navy’s black lung disease.

Over the past two years there has been much discussion in the Navy about the impact of fatigue on watch standing, maintenance, and operations at sea. The collisions in 2017 and ensuing investigations revealed the problem in an operational sense, and, to its credit, much of the Navy has adopted crew endurance and fatigue management programs. Missing from the conversation, however, is Navy leaders’ duty to the lifelong health of the force and the positive impact that broader education and policy changes could have on Navy life.

Having studied this problem up close—starting as a tired watchstander/shift worker and later serving as a commanding officer and then chief of staff at the surface type commander—I, and a small group of human systems integration professionals, spent years advocating the service take a comprehensive approach to crew endurance. I was pleased when a policy finally came to fruition in the surface navy. In the past two years, since the promulgation of a formal fatigue and endurance management policy by Commander, Naval Surface Forces, and similar initiatives in submarines and aircraft carriers, the Navy has started to turn the cultural corner, recognizing that people need a scientifically proven level of rest, recuperation, and sleep to optimize their performance.1

There are mountains of research and countless articles about the operational impact of fatigue; it is front and center in the National Transportation Safety Board report on the collision involving the USS John S. McCain (DDG-56) and other records of maritime mishaps and near misses.2 Sailors and their families dedicate their lives to the Navy, and they are rewarded with a lifestyle that inflicts both mental and physical stress for years, affecting their health long past the end of their active service. The Navy can do better.

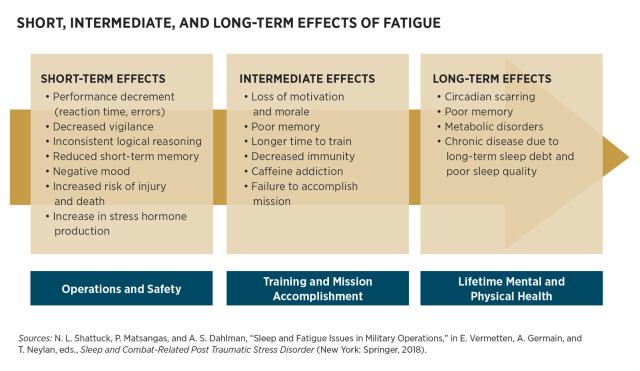

Studies by the Naval Postgraduate School have categorized a full range of effects from fatigue, from short to long term.3

A Missed Waypoint

In March 2014, RAND conducted study on sleep in the military that included more than 80 medical, research, and operational stress experts from all active services. The study was commissioned by the military and produced extensive background data on the causes and effects of fatigue in military operations and a precise set of well-vetted recommendations on how to address these issues. The language was quite strong, as the following paragraph from the study’s abstract demonstrates:

Sleep problems often follow a chronic course, persisting long after service members return home from combat deployments, with consequences for their reintegration and the readiness and resiliency of the force. Therefore, it is critical to understand the role of sleep problems in service members’ health and functioning and the policies and programs available to promote healthy sleep.4

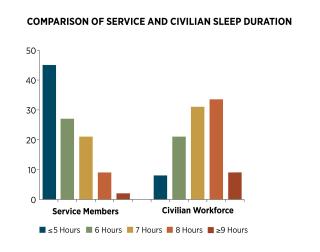

In January 2013, an Army-sponsored study found a high prevalence of sleep disorders and a high rate of short sleep duration among active-duty military personnel. The study suggested the need for cultural change toward sleep practices throughout the military. “While sleep deprivation is part of the military culture, the high prevalence of short sleep duration in military personnel with sleep disorders was surprising,” said Dr. Vincent Mysliwiec, the study’s principal investigator and lead author and chief of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine at Madigan Army Medical Center in Tacoma, Washington. “The potential risk of increased accidents as well as long-term clinical consequences of both short sleep duration and a sleep disorder in our population is unknown.” Results show that the majority of participants (85.1 percent) had a clinically relevant sleep disorder. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) was the most frequent diagnosis (51.2 percent), followed by insomnia (24.7 percent). Participants’ mean self-reported home sleep duration was only 5.74 hours per night, and 41.8 percent reported sleeping five hours or less per night. (Seven to eight hours is the scientifically recommended amount for an average adult).

When coal miners started dying of strange diseases that affected their lungs, the scientific community found a connection to the coal dust they breathed day in and day out. Industry pressure resulted in a government strategy of denial and delay that suppressed research that would prove a connection between working conditions and the workers’ illnesses. This continued for most of the 20th century, and although progress has been made, there still are pockets of denial. There probably are parallels in other areas closer to the Navy (mesothelioma and Agent Orange, as well as mold in military housing) where the natural first response is to consider the cost of long-term medical care and then to try to minimize the financial impact. The intent is not to conflate different responses—there is no active resistance or misinformation campaign to avoid addressing stress and fatigue among military personnel—but doing nothing to manage the issue at a force level can have the same result.

Turning the Corner

After the punch in the gut that was 2017, most type commanders have implemented some variation of a fatigue management program and mandated circadian watch rotations. This is a good step, but does not come close to the Department of Defense (DoD)/Navy-level recommendations of the RAND study, nor does it address the root causes and long-term effects. Although the recommendations of that study are not binding, leaders must take care of their people. Looking back again, to 1969, Congressman Ken Hechler (D-WV), speaking to a crowd of miners at a rally in Charleston, West Virginia, summarized the coal industry’s reaction to the scourge of black lung:

Now the coal operators and some doctors who seem to be close to the coal operators say that there is no such thing as black lung, or if there is, maybe it won’t hurt you. But if it does hurt you, we’d better not compensate you for it. But in case we do compensate you for it, we had better study this subject scientifically. We’d better refer this whole question to an impartial board of other coal company doctors. Then we’ll study it for five, or 10 or 15 years, and by that time either the problem will go away, or your lungs will go away.5 (Emphasis added.)

Later the tide turned, and other U.S. senators crafted legislation to reform the black lung benefits program, using a series of reports by the Center for Public Integrity and ABC News as a guide. Senator Robert Casey (D-PA) took a different approach, saying, “The system didn’t work” for ailing miners. “Their government failed them as well as their company failing. So, we have, I think, an abiding obligation to right this wrong.”

The Navy has emphasized the operational and safety repercussions of fatigue; however, missing from the conversation is the obligation the service has to the long-term health of its workforce.

Getting Back on Course

So, what should the Navy do? Well, the list RAND gave the military in 2015 is a good start. It is surprising that DoD would commission such an exhaustive study, get the results, and then do little with them. The collisions of 2017 injected energy into the system, but it has not been sustained or leveraged as well as it could be.6 To be fair, some parts of the Navy have implemented operational policy, but there is still much that could be done to educate the force and address the long-term effects of fatigue. Here are a few ways to put several of the RAND recommendations into action immediately:

Educate the force. Develop a general military training topic on fatigue, its physiological effects, and how to combat it at the personal and unit level. Designate the Naval Postgraduate School as a “Center of Excellence” to consolidate Navy-wide training.

Educate leaders. Add a module to all accession and pipeline training to address fatigue management, crew endurance, and its impact on operations and long-term health. The Naval Postgraduate School already has developed just about everything needed for this effort.7

Change the culture: Incorporate training on fatigue mitigation into the Flag Officer Capstone Course to educate rising flag officers on the importance of this topic.

Build a reservoir of medical data as the foundation for action. The DoD medical community should review the recommendations and report where they could be implemented.

Be a learning organization. Coordinate a DoD-wide policy and process review to capture the progress in different areas throughout the Navy. Leverage the good work of the surface force and submarine force and provide overarching policy guidance.

Fix manpower and manning documents to match human factors requirements. Continue the ongoing manpower studies to capture the requirements needed to perform maintenance, man a four-section circadian watch, and execute all operational tasking.

Upgrade ship design. Leverage existing technology to refit berthing compartments to decrease noise, improve lighting and ventilation, and improve the physical environment in which our sailors sleep every night.

Much of this material and knowledge already exists—for example, the Naval Postgraduate School recently overhauled its crew endurance website. However, more than two years after the 2017 mishaps, that it still has not been incorporated into the fabric of Navy training culture is frustrating and a travesty.

Some final words from the 2015 RAND study:

This study offers 16 policy recommendations to promote sleep health in the domains of prevention, identification, treatment, and training/operations. These recommendations should be addressed collectively by individual service members, unit leaders, the military health system, training and operational commands, military health researchers, and DoD at large. Implementing these recommendations must go hand in hand with better messaging about the biological and operational necessity of sleep to overcome cultural, environmental, medical, and operational barriers to achieving healthy sleep among service members. Carrying out such an integrated approach is critical for improving sleep, which is an important contributor to resilience and operational readiness in the U.S. military.8 (Emphasis added.)

Would the 2017 collisions have been avoided if these actions had been taken? We will never know, but the words above are almost prescient. The data was there on the risks to operations, as it is now on the long-term health risks of fatigue. The difference is there will be no catastrophic event to act as a catalyst, but it will happen—to each person individually, quietly, and personally. Will the Navy follow the path described by Congressman Hechler and “study it for 10 or 15 years—until [we] go away?” Or will the service act to preserve the lives and health of its sailors?

In many ways, service members today are like the coal miners of yesteryear, and will live with the effects of chronic fatigue for the rest of their lives. DoD and Navy leaders have the power, and “an abiding obligation,” to take corrective action to change the culture and operational habits that contribute to unnecessary exhaustion and sleep deprivation.

1. Department of the Navy, Comprehensive Fatigue and Endurance Management Policy, 30 November 2017.

2. National Transportation Safety Board, “Collision between U.S. Navy Destroyer John S McCain and Tanker Alnic MC” (June 2019).

3. Naval Postgraduate School Crew Endurance Team, Crew Endurance Handbook: A Guide to Applying Circadian-based Watch Bills, Version 1 (2017).

4. W. M. Troxel, R. A. Shih, E. Pedersen, L. Geyer, M. P. Fisher, B. Griffin, A. C. Haas, J. R. Kurz, P. Steinberg, “Sleep in the Military; Promoting Healthy Sleep Among U.S. Servicemembers” (Santa Monica, CA: Rand, 2015).

5. Chris Hamby, “A Century of Denial on Black Lung,” Center for Public Integrity (May 2014).

6. Troxel, et al., “Sleep in the Military.”

7. Naval Postgraduate School, “Crew Endurance.”

8. RAND, “Sleep in the Military.”