The Coast Guard has a distinct blend of military and civilian-like missions. The distinction is clear compared with other branches of the U.S. military, other government agencies, or even other countries’ respective maritime forces. Often, this blend is an asset to the service because of how it enables integration on a U.S. or allied naval vessel with law enforcement authority, or the ability to respond nimbly to natural disasters. The Coast Guard has limits, though, particularly in computers and networks.

The Coast Guard’s dual role as a military service and a regulatory public safety agency means that it needs its own information technology (IT) governance, specifically on secondary networks to carry out missions that cannot take place on primary networks. Creating a secondary network would improve mission support while protecting the critical Department of Defense Information Network (DoDIN).

The choices to permit or deny network traffic technically are made at individual firewalls, servers, switches, and routers that make up a network, but most large-scale networks tend to operate on “default deny” or “default permit” premises—default settings that most network security equipment require. That underlying network philosophy determines how a network is structured and monitored, how applications are built on top of the network, and how users interact with data. A default deny stance requires explicitly deciding what sort of traffic is allowed in or out of the network. The safest network is one that allows no traffic in or out. Like a building with no doors or windows, however, it has limited utility and cannot serve broader mission needs. While the Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA), which controls the majority of policy on DoD information networks, does not declare or require a full default-deny policy, many of its requirements effectively impose such a posture, especially for interactions with external entities.

The Coast Guard’s main network, CGOne, exists as an enclave within the DoDIN, which has wide-ranging benefits of management, cost, interoperability, and security. The Coast Guard’s IT needs, however, often deviate substantially from that of DoD, particularly because a great deal of mission-essential Coast Guard communication involves non-DoD entities. DISA governance of CGOne causes occasional disconnects where an upstream network policy impacts Coast Guard or public end users trying to access a Coast Guard application or data. To play by DISA’s rules, the Coast Guard has to rework applications, apply for exceptions to DISA rules, or stop supporting applications or services.

There is distinct incongruence having a default-deny posture while the Coast Guard also maintains its role as a regulatory and public safety agency. The other military services generally lack the role of the Coast Guard as arbiters of information to the public. While all military services must comply with FOIA requests, the Coast Guard also gathers data from the private and public sectors and supplies data to them—important types of data, including commercial ship arrival and departure information, U.S.-flagged commercial ship locational data, voluntary ship position reports for search and rescue purposes, and secure communications with mariners. For all this information and more, the Coast Guard must maintain general web services to enable sharing with the public.

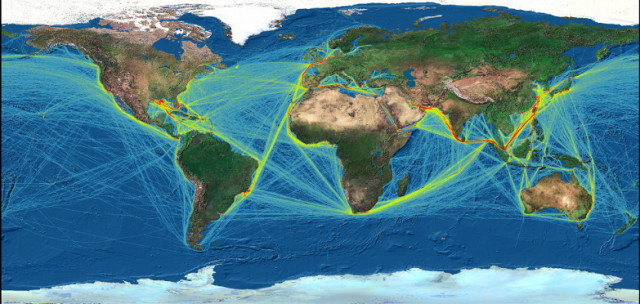

Search and rescue is one area where an alternative network solution would benefit the Coast Guard’s ability to receive and share information. In the middle of the ocean, there are few Coast Guard or Navy assets that can be diverted to respond to a distress call. There are, however, countless commercial vessels constantly transiting all shipping lanes. That is where the Automated Mutual-Assistance Vessel Rescue System (AMVER) comes in. A voluntary program, AMVER’s purpose is only to facilitate search and rescue, with hard limits against using the ship position data for any other purpose. There is no need to share the data on classified networks because it cannot be used for law enforcement or other purposes, so including it in military networks offers no additional benefits. Yet, currently the Coast Guard system that handles AMVER data is subject to DISA regulation, which costs extra money and places unnecessary restrictions on its use. AMVER benefits from participation from as many ships as possible to increase the odds of a ship being able to respond to an emergency on another ship. Default-deny postures can result in accidental blocking of submission of position reports, particularly coming from commercial server or email domains as most submissions to the Coast Guard’s AMVER system do. IP address or domain whitelisting, or explicit allowance, can only go so far with new participants and seemingly endless new communication providers.

Rescue System (AMVER). This graphic depicts traffic patterns and density of AMVER reporting.

Another example that demonstrates the need for a secondary network is the Long-Range Identification and Tracking (LRIT) system, which shares a lot of characteristics with other information systems, namely ship positional data. The difference, however, is that LRIT is a system mandated by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and, as member a state, the United States must comply with the IMO’s LRIT governance rules. One of the key features of the LRIT system is the requirement that countries share their own respective flag ship positions with other countries. For example, the U.S. LRIT system shares the position of a U.S. flag merchant ship with Italy when it approaches that country’s coast, and China must provide position data for its merchants to the United States when they approach the U.S. coast. Fortunately, the global LRIT system relies heavily on the International Data Exchange (IDE), which distributes data to the countries that are entitled to it. This alleviates some of the concerns about the classic networking problem by having a hub-and-spoke type model rather than hundreds of crisscrossing nodes. The primary site for the IDE is the European Maritime Safety Administration, and the backup site is the U.S. Coast Guard’s Operations Systems Center, in Martinsburg, West Virginia, where the majority of the service’s other business IT applications are housed, including the U.S. version of LRIT.

Simply connecting the U.S. LRIT to the IDE is a challenge of its own in a military network, but the level of complexity required to operate the backup IDE site is even more challenging. Specifically, the IMO requirements laid out in the Continuity of Service Plan for the LRIT System state “the IDE operator should be cognizant of firewall restrictions at the DR [disaster recovery] site and should ensure there are no restrictions at the DR site on the IP addresses accessing the production system.” For a default-deny network, this sort of open traffic communications requires a lot of control, and it also requires other participants to keep their own systems relatively static. With limited control over the outer edges of the network, and other countries changing their own system configurations and IP addresses in accordance with internal cybersecurity practices, this is a Sisyphean task that forces the U.S. Coast Guard out of compliance with its own obligations.

While these two systems that deal with public ship position information are clear cases of how and why hosting within the DoDIN is incompatible, there are other efficiencies and improvements to be found from hosting other applications or portions of applications outside DoD networks as well. There are a number of other services that allow the public to send information into or extract it from Coast Guard applications, such as web services that enable third-party developers to build their own applications for arrival and departure information for ships. A cruise line, for example, might want to build a feature into its own internal voyage planning software, or a container line might want to be able to submit bulk uploads for its regularly scheduled services, saving the ships’ masters from individually entering each port call. In networking, a widely employed concept is known as a “demilitarized zone,” (aptly named for its analogous real-world version) which exists outside a primary network and is open to the broad internet. Using the earlier building analogy, a network demilitarized zone offers an unlocked door into the building’s empty foyer where there is yet another door protecting the main parts of the building. The necessary data from the Coast Guard’s primary network, CGOne, could still be shared with this secondary network, but keeping the public interfaces separate would enable a degree of separation and security while maintaining connectivity to the public.

The Coast Guard’s flexible authorities and varied operational capabilities allow it to meet its many missions. In the IT realm, however, the Coast Guard needs greater flexibility to deviate from DISA’s military network practices and standards. Because the Coast Guard operates within military, law enforcement, and regulatory environments and must partner with public and private-sector entities, it requires a non-DISA secondary network to fulfill its obligations to other government agencies, foreign partners, and the public.