The need for a program to hone Navy fighter tactics became clear in the early years of the Vietnam War. During those first years, the probability that a U.S. air-to-air missile would destroy its target was roughly 10 percent.1 A great deal of this could be attributed to poor missile reliability, but many missiles were launched out of their effectiveness envelope, which indicated a training problem. Rules of engagement that required visual identification before taking a shot made things worse all around.

U.S. Navy aircrews were flying the most modern fighters in the world—the F-4 Phantom II and F-8 Crusader—against a relatively primitive foe in the North Vietnamese air force, yet the Navy’s kill ratio was only 2.5:1. Kill ratio is a common yardstick of fighter performance; it indicates the number of enemy aircraft destroyed for each U.S. fighter lost. In World War II, which ended just 20 years before the air war in Vietnam started, the U.S. Navy’s kill ratio was 14:1. In the Korean War, American jets had a 12:1 kill ratio. Clearly, something had to be done.

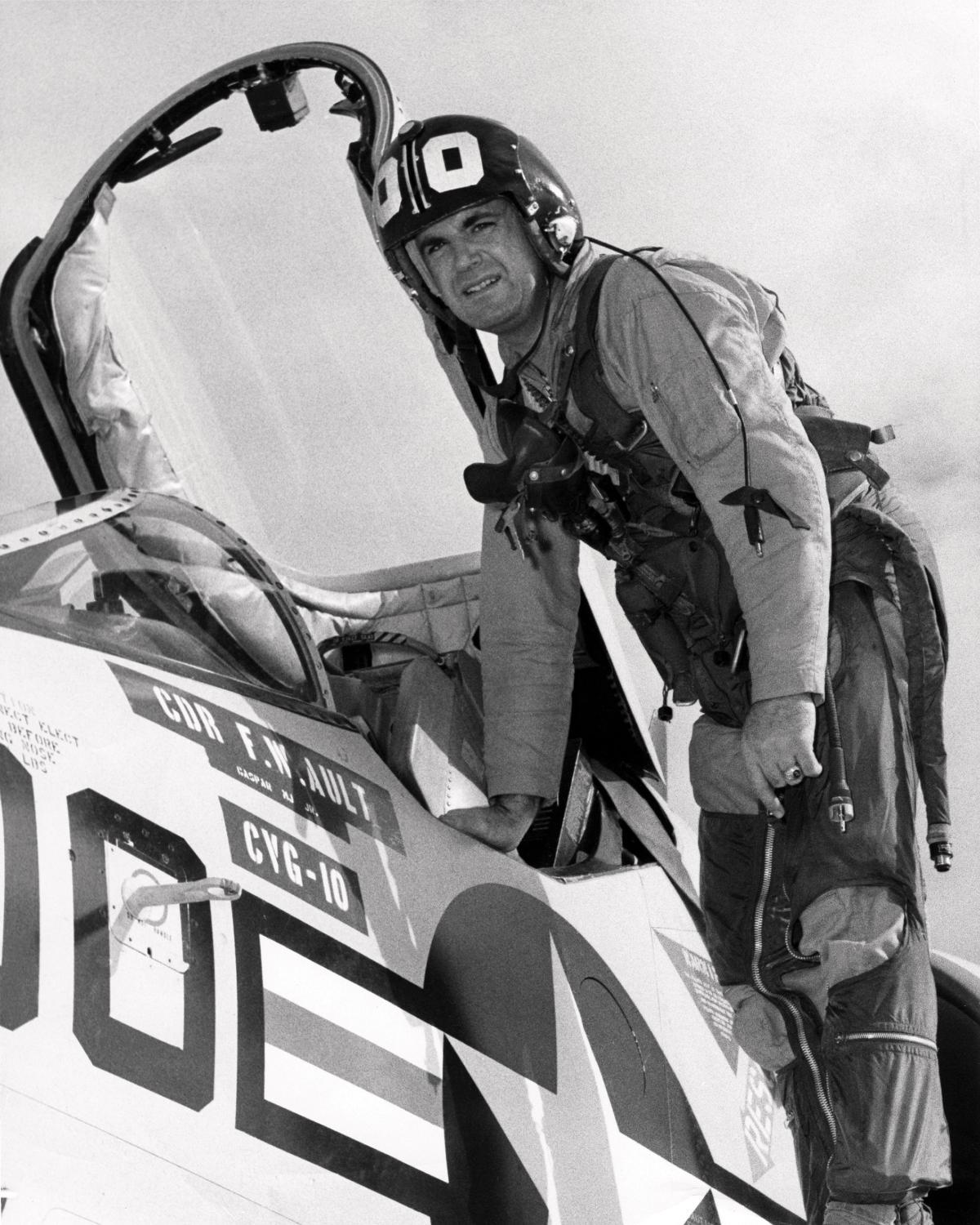

Credit goes to Navy leaders for ordering an in-depth study of air-to-air missiles, aircraft, and radars, as well as the training and tactics of aircrews. The official title of the study was Report of the Air-to-Air Missile System Capability Review, but it has become known as the “Ault Report” after the leader of the study’s team, Captain Frank Ault, U.S. Navy. Ault was a World War II veteran pilot who, in 1966–1967, commanded the USS Coral Sea (CVA-43) during Vietnam combat operations. He possessed both the talent to lead a comprehensive investigation and the backbone to publish its findings without pulling punches. The team examined “the complete spectrum of influences on weapon system . . . performance.” They had the right mind-set, as evidenced by this statement in the report: “The need for new approaches and innovations appeared self-evident.”2

Ault’s team spent three months gathering information, then published a comprehensive and hard-hitting report offering 104 recommendations. A sense of the range of matters evaluated can be found in this sample: Realign the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) organization, at the very top of the Navy hierarchy, to clarify responsibility for matters related to air-to-air missiles; conduct a quality control study of AIM-7 Sparrow missile manufacturing; and develop new missile test equipment for use on aircraft carriers to ensure system readiness.

While addressing technical and reliability flaws in the equipment, Navy decision-makers also considered the need to improve training. The Ault Report made several recommendations to address shortcomings in aircrew training, including: Establish instrumented ranges to support accurate debrief of training, to help aircrews recognize when they were “in the envelope” for launching missiles; and establish an “Advanced Fighter Weapons School” with a core of instructors to consolidate, coordinate, and promulgate doctrine and tactics for fighter employment—thus, TOPGUN was born.

The Navy had operated a fighter tactics and weapons training unit before—the Fleet Air Gunnery Unit—but disbanded it in 1960 with the increased emphasis on missiles and related technology. The Ault Report noted that the concept of a weapons school was already under consideration at NAS Miramar, the San Diego airfield that was home to Pacific Fleet fighter squadrons and proudly nicknamed Fightertown, USA. Under consideration, however, is a long way from training combat aircrews.

In reestablishing a dedicated fighter weapons school, the Navy started modestly by assigning the task to officers at Fighter Squadron-121 (VF-121), the F-4 fleet replacement air group (RAG) training squadron for the U.S. Pacific Fleet. With virtually no funding, nine pilot and RIO instructors commandeered a trailer to use as office and classroom, and went to work building the new school while still fulfilling their duties as RAG instructors. Led by Lieutenant Commander Dan Pedersen, they gathered intelligence on enemy aircraft, studied engineering information, and flew dogfights on training ranges, challenging any American fighters who would play and even some actual MiGs operated by the United States in a then-super-secret program in Nevada, called “Constant Peg,” which has since been declassified. The instructors prepared lesson plans, practiced their lectures, and opened the door for the first class in March 1969—quite an accomplishment, considering the Ault Report was published 1 January 1969.

In a grainy old photograph, you can read the sign above that trailer: “TOPGUN.”

The new school faced many hurdles. Navy and Marine Corps F-4 and F-8 squadrons scrambled to send their best pilots (and RIOs, for the F-4) to TOPGUN for four weeks while also training for deployment to Vietnam. Several senior officers had other ideas as to how the Navy should improve its training, or simply did not want to see the program succeed. These existential threats were faced down. The whole colorful story has been told in several books, including Scream of Eagles, by Robert Wilcox, and this year’s TOPGUN: An American Story, by Pedersen himself.

TOPGUN operated as a department within VF-121 for several years. It was commissioned as a stand-alone squadron in July 1972 as the “Navy Fighter Weapons School” (NFWS). But the name TOPGUN stuck.

A Culture of Excellence

When considering why TOPGUN flourished, much credit belongs to the enduring, rigorous culture established by the earliest instructors and handed down to their successors. Much of this culture was essential to a school for fighter aviation, such as obtaining accurate intelligence and developing effective tactics. The following items, on the other hand, were matters of choice that became part of the standards that defined TOPGUN.

Exceptional technical knowledge

Each instructor had to become an expert on at least one assigned subject, such as the intricacies of radar-guided missiles or one-versus-one maneuvering. To prepare, instructors focused on the most detailed intelligence available and sometimes attended specialized training. They were, after all, teaching aviators who would be taking the lessons into combat.

High presentation standards

Although the topic was dogfighting and missiles—topics exciting enough for comic books and Hollywood movies—instructors had to meet the highest standards for lecture delivery: two-hour lectures with no notes; neat handwriting and diagrams on the board; and a pointer (pre-laser-pointer) held with both hands for accuracy and control. These and dozens of other guidelines were explicitly stated and were checked in “murder boards” (the aptly-named lecture approval process), along with technical knowledge. These standards resulted in disciplined, professional lectures that helped establish TOPGUN’s reputation.

Skilled aviators

Matching the technical knowledge

and lecture discipline, instructors were required to have a high level of stick-and-throttle skill so they could challenge students who were flying aircraft that were in many ways superior. This also emphasized TOPGUN’s philosophy that aircrew skill and training can overcome deficiencies in aircraft and weapons.

Objective debriefs

Fighter pilots and RIOs are naturally competitive, so when a young crew in an F-4 Phantom was “shot” by an instructor in a TA-4 Skyhawk, the event would have to be debriefed accurately and thoughtfully to prevent alienating the students. In addition to the actual maneuvers, instructors debriefed the physics, tactics, and other factors that affected engagements, emphasizing learning points rather than keeping score. This greatly reduced the “ego factor.” The instrumented ranges developed as recommended in the Ault report aided detailed debriefing.

End product: expert squadron training officers

Any fighter crew would improve after weeks of intense flying and training, but the point of TOPGUN was to develop aviators who could return to their squadrons and pass along their knowledge to others. In addition to the tactical and technical material, TOPGUN presented lectures on “teaching and learning” and “briefing and debriefing” to give students the tools they needed to be exceptional training officers.

Adversary Instructor Program

Several years after TOPGUN started, the Navy established adversary squadrons at bases around the country to provide valuable training to all tactical air squadrons. TOPGUN was the lead for adversary standardization, helping to ensure uniform high quality throughout the fleet.

These aspects of TOPGUN helped it survive as an organization while the Navy changed. It started on a shoestring and continued to run that way for several years. Lack of personnel was a significant problem, for example, that wasn’t truly rectified until the squadron performed a Navy manpower study and went from a complement of 70 enlisted personnel to 130 and also doubled the number of officers.

Established during the Vietnam bombing halt that began in March 1968, TOPGUN operated for three years before the air war resumed in full. When it did, the kill ratio for Navy fighters increased to as much as 13:1, and TOPGUN graduates scored the majority of the Navy’s MiG kills.3 The school was here to stay.

Course Corrections in the Mid-1980s

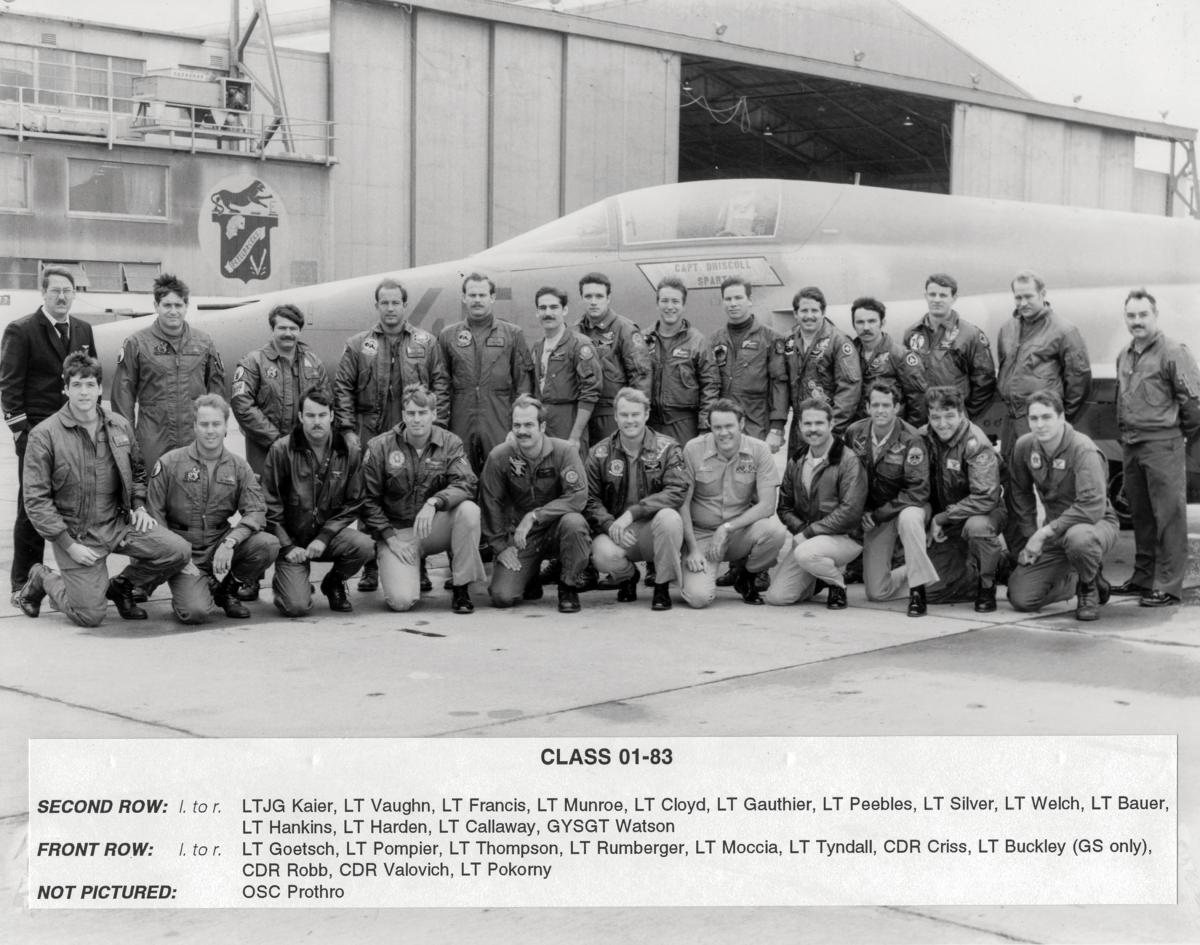

I joined my first fleet fighter squadron as an F-14 RIO in 1981. In 1982, I attended the 5-week-long TOPGUN course as a student, and in 1984 I was selected to return as an instructor.

Through murder boards and discussions with other instructors, I learned the squadron’s history and foundational elements. The developments that follow occurred during my two-and-a-half-year tour as an instructor, and in my opinion contributed to TOPGUN’s continued validity through evolution.

Introduction of forward-quarter capable threat

While the poor success rate of the AIM-7 Sparrow missile during the early years of the Vietnam War prompted, in large part, the Ault Report and TOPGUN, much had been done to improve the missile and aircrew employment practices. As a result, in the early 1980s, Navy and Marine Corps fighters enjoyed a significant advantage over many threat aircraft, which did not have the ability to effectively launch a missile while approaching a target in the forward quarter.

The MiG-23 Flogger and its AA-7 Apex missile, however, were becoming more numerous in Soviet and other air forces. Floggers, along with other aircraft and missiles, posed a new threat that necessitated new tactics. The offensive and defensive considerations of forward-quarter missiles resulted in significantly more complex tactics. TOPGUN increased its presentation of the MiG-23, simulated by F-5s and A-4s, while reducing simulation of older threats such as the MiG-17.

Division tactics

The Navy and Marine Corps use the term “division” to identify a flight of four aircraft. Two-plane operations (a “section” of fighters) had been the norm for the Navy for decades, but against the challenge of a forward-quarter threat and the prospect of large formations of enemy fighters observed in Soviet exercises, TOPGUN realized that four aircraft provided a substantial increase in tactical flexibility and firepower, and began to increase division flights in the syllabus.

Tactical night flight

All branches of the U.S. military perform a great deal of training and actual combat at night, but most TOPGUN training culminated in a close-in maneuvering dogfight, which required clear visual contact to be effective and safe. As weapons and tactics advanced worldwide, however, TOPGUN realized that opponents would likely launch aircraft at night, and that its graduate-level training for U.S. fighter crews should include night ops. So, in 1986, TOPGUN added a nighttime syllabus training mission. It was a carefully controlled event with limited objectives, but it was a first step toward the nocturnal air-to-air combat training that has become common.

TOPGUN always took its mission seriously. Committed instructors strove to master flying and teaching responsibilities. By the mid-1980s it seemed that senior elements in the Navy were also taking advantage of this valuable resource, because TOPGUN was designated an “echelon two” command. The significance of this designation can be gleaned from these quotes from the program of a 1986 change of command ceremony: NFWS became the “primary authority for tactical development and training (for) fighter employment in the power projection role,” and was expected to “provide directly to the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) advice and recommendations on planning, programming, and budgeting requirements and priorities.” Some of the practical results of this designation included greater involvement in writing aircraft tactical manuals (in collaboration with the VX-4 and VX-5 operational test and evaluation squadrons) and working with tactics analysis teams that examined and reported on threat fighter operations around the world.

While the mid-1980s saw significant developments that maintained TOPGUN’s relevance, important changes lay ahead.

Profound Changes, Yet TOPGUN Endures

All organizations either evolve or expire, and TOPGUN is no exception. Over the years and decades, TOPGUN underwent additional changes. Some were necessitated by the increasing complexity of warfare, while others were the result of more mundane influences. Briefly, here are a few of the more significant events that have shaped TOPGUN since the mid-1980s.

Changes in aircraft and flying role

In the 1980s, TOPGUN’s A-4s and F-5s were very good simulators of threat aircraft . . . that were built in the 1960s and 1970s. They were simply inadequate, however, to simulate emerging 4th generation threats. The Navy effectively addressed this by procuring F-16s, which were excellent opponents, followed by F/A-18s and even F-14s with which to challenge students. Today, however, some aircraft flown by potential enemies are equal to the very best American fighters, and TOPGUN is struggling to replicate that capability.

Along with these changes, in the 1990s instructors started flying as part of student formations during the class, known as “Blue Air.” During the early years, TOPGUN instructors had taught students about the weapons and tactics of American and threat forces, but only flew as Red Air—opposing the students during the class. While they continued to do so, they added the Blue Air role, which allowed instructors to get an even better sense of student performance and more insight into problems that needed to be addressed.

Air-to-ground training

All Navy fighter squadrons have been strike-fighters since the mid-1990s, when F-14s added the air-to-ground mission. The Hornet and Super Hornet always have been strike fighters. To support training requirements for both missions, TOPGUN added air-to-ground to the syllabus. The class was lengthened to nine weeks to accommodate the additional training. I wasn’t there for it, but I am sure there were vigorous arguments on both sides of the question of whether to add air-to-ground to a syllabus that had previously been strictly air-to-air. They made the right decision.

Move to NAS Fallon and incorporation into NAWDC

In 1996, when NAS Miramar became a Marine Corps air station as a result of Base Realignment and Closure, TOPGUN moved to NAS Fallon, Nevada. Any argument over this question would have been futile. The organization lost its echelon two status and was incorporated into the Naval Strike and Air Warfare Center (NSAWC), which later became the Naval Aviation Warfighting Development Center (NAWDC). While these changes caused turbulence within an organization that had been independent and aggressive, the dedicated instructors remained true to their mission and heritage, and TOPGUN survived. One benefit of the move (geographic and organizational) has been greatly improved pre-

deployment training for entire carrier air wings during their Fallon detachments.

A Center of Excellence

TOPGUN instructors have assigned to themselves a significant burden: excellence on the ground and in the air. It can be seen in their lecture presentations, flight briefings, mission conduct, and debriefs. New instructors willingly accept this burden and strive to live up to the standards. Created long before the term “center of excellence” entered the

Navy’s vernacular, TOPGUN personifies the term.

This list of significant events in TOPGUN’s 50 years is based on my own experience and is weighted toward the timeframe I was there. Many more events contributed to the school’s continuing effectiveness, yet no specific event can compare to the commitment each individual instructor makes to the highest level of professionalism. This level of commitment was not dictated by the Ault Report but is found within each instructor and is demanded and facilitated by his and her squadron mates.

1. Marshall L. Michel, Clashes: Air Combat over North Vietnam, 1965–1972 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997), pp. 151–154: summary of 527 launches of AIM-7 and AIM-9 missiles, resulting in 56 kills. The Ault Report opened with a similar conclusion; page 1, paragraph one. Michel also reports that air-to-air gun kills and the Air Force-only AIM-4 missile were in the same effectiveness range (pp. 156–159).

2. The Ault Report, pp.5–6.

3. Many sources report a 13:1 kill ratio for the Navy during the second phase of the air war in Vietnam based on 26 kills and 2 losses to MiGs. Michel (p. 277) and several other sources, however, report a kill ratio of 6.5:1 based on 26 kills against 4 losses.

Author’s note: Much of the material for this article came from my personal experience and notes from my time as a TOPGUN instructor (1984–87). In preparing this article, I consulted former TOPGUN instructors Captain John Monroe Smith, U.S. Navy (Ret.), Lieutenant Colonel Mike Straight, U.S. Air Force (Ret.), and aviation historian Major Patrick Catt, U.S. Air Force (Ret.). Their assistance is greatly appreciated. Any errors or omissions are solely my responsibility.