The history of naval aviation is full of different methods of getting aircraft into the fight. The aircraft carrier is the safest and most efficient means of taking fixed-wing air power to sea, but that has not stopped navies around the world from trying unorthodox or even desperate methods—airships, submarines, merchantmen, and even a direct sea-takeoff method all were tried and ultimately rejected. Ironically, some of these past failures could soon return, riding the coattails of the unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) revolution.

The period between World War I and World War II saw considerable experimentation, as navies around the world grappled with not only how to use naval aviation, but also where to base it. In 1925, the U.S. Navy operated the USS Langley (CV-1), its first and—for a time—only seagoing aircraft carrier. The Navy also had its first airship, the USS Los Angeles (ZR-3). A German-built zeppelin, the Los Angeles was used to test fixed-wing takeoff-and-landing concepts from airships. The theory was that flying carriers would be cheaper and require smaller crews than their seagoing counterparts while still fulfilling the mission of scouting for the main battleship force.

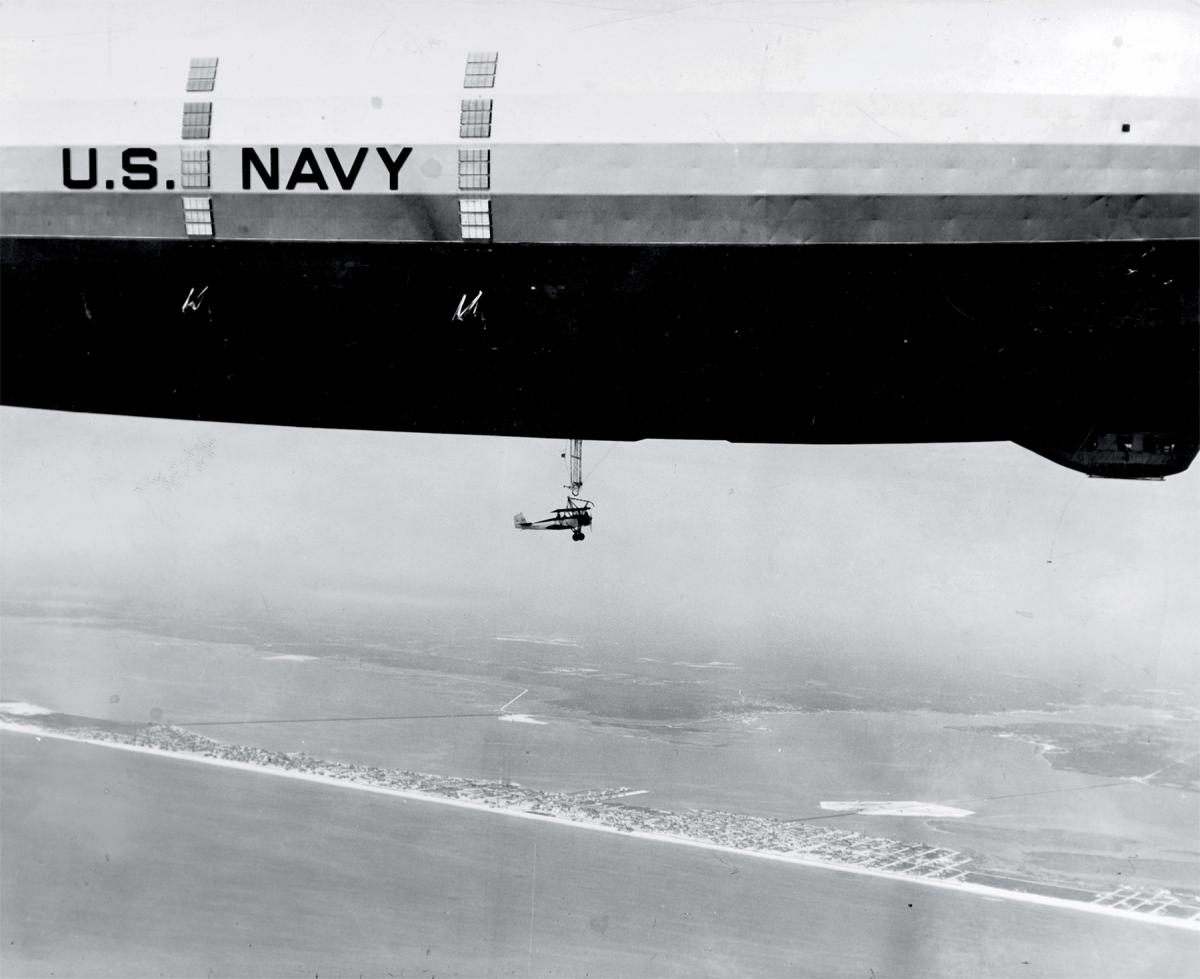

The tests were successful enough to prompt the Navy to construct two airships, the USS Akron (ZRS-4) and USS Macon (ZRS-5). Each “flying aircraft carrier” was fitted with a small hangar and a trapeze mechanism to launch and recover aircraft. The airships carried up to five F9C-2 Sparrowhawk lightweight aircraft—nominally “fighters” but mostly useful as scouts. The airships experienced a number of issues during their short operational careers, particularly during high winds. The program effectively ended in the mid-1930s with crashes of the Akron in 1933 and the Macon in 1935.

During World War II, the Allies were unprepared for Germany’s use of long-range aircraft—such as the Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor, with a 2,000-mile range—to attack convoys and provide intelligence to U-boats. German submarines, with their limited visibility and detection range, often stumbled onto Allied shipping by accident, but spotter aircraft allowed coordinated attacks over a vast area. The Allies could assist convoys with their own land-based aircraft from the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, but fighters had limited range.

Short of real aircraft carriers, the Royal Navy in desperation fitted five merchantmen with a rocket-catapult launch system. Catapult-assisted merchant ships—CAM ships—could be loaded with a Hurricane fighter that would be flung into the air in emergencies to intercept enemy aircraft. After the engagement, fuel running low, the pilot would ditch his plane in the ocean and (it was hoped) be picked up by a convoy escort. The catapult system’s postwar discontinuation speaks to the desperation involved in sacrificing a fighter plane—and possibly a pilot—to protect convoys. As the war went on, the CAM ships were replaced by much more capable escort carriers embarking up to two dozen aircraft each.

After the war, the U.S. Navy considered reviving the convoy fighter project, with a twist. The Navy anticipated that, in the event of war with the Soviet Union, the United States would again have to flow forces across the Atlantic against submarine opposition. In the late 1940s, the Navy asked industry to develop a turboprop-powered fighter capable of vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) from empty spaces on merchant vessels. The “tailsitter” would rest nose pointed straight up, sitting on oversized horizontal and vertical stabilizers. Five concepts entered the competition but only two, the Lockheed XFV and the Convair XFY Pogo, proceeded to the prototype phase and actually flew.

But the designs proved dangerous and unreliable, and by the time the planes were flying it was clear the VTOL execution was too demanding. The fast pace of aeronautical development meant that subsonic speed—initially an acceptable trade-off for getting a fighter aircraft onto merchant ships—quickly became a liability. The concept was shelved in the mid-1950s.

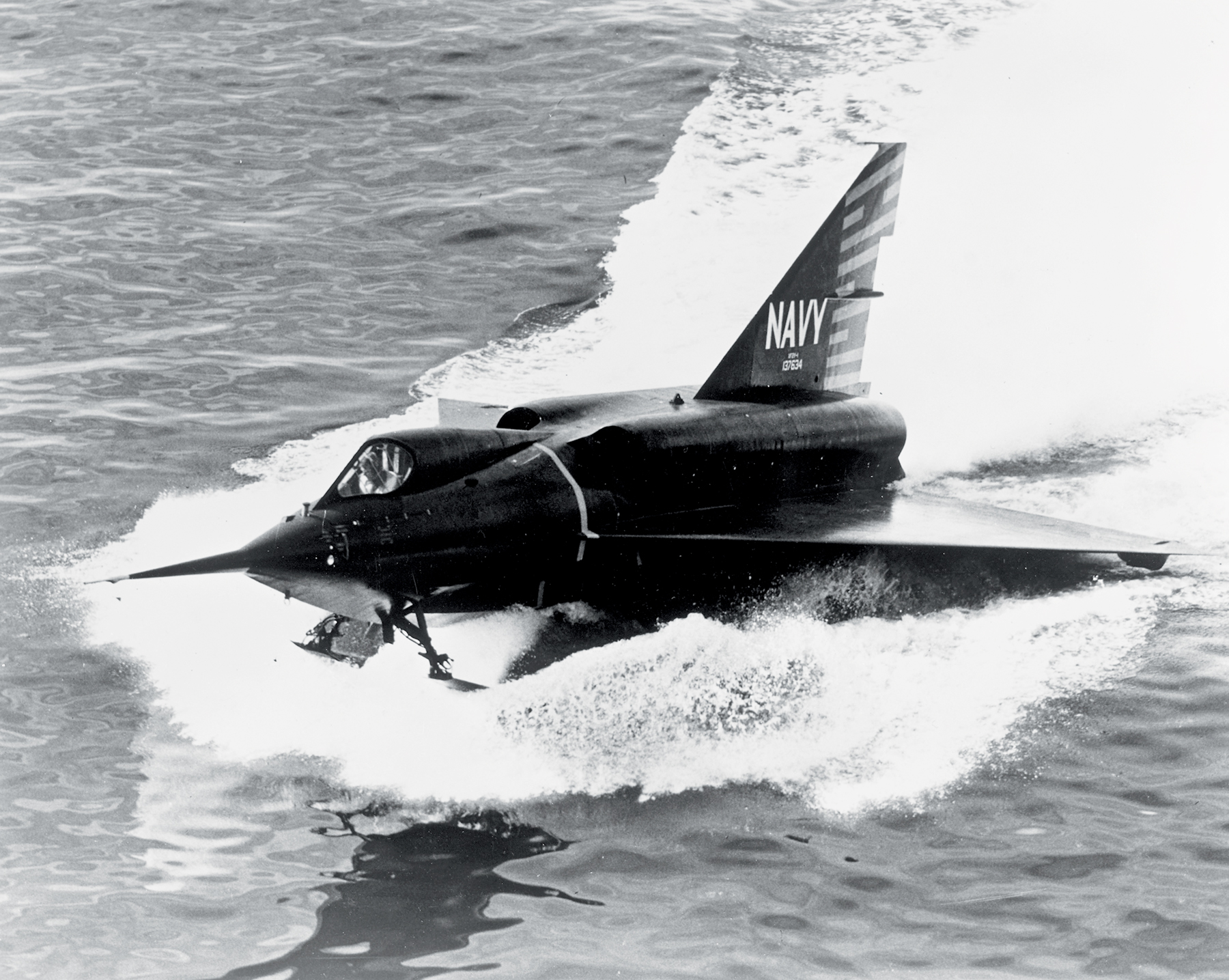

The Navy was concerned that operating high-performance jet fighters from carrier flight decks might be unworkable. So, also in the early 1950s, the Navy proposed a solution that eliminated ships entirely: the Convair XF2Y-1 Sea Dart. The Sea Dart had a delta-wing design like the Air Force’s Convair F-106 Delta Dart, but there the similarities ended. The Sea Dart was a seaplane, a supersonic fighter designed to take off from and land on the surface of the ocean using retractable skis.

Five Sea Dart fighters were built. The aircraft was difficult to fly and particularly difficult to land, in large part because of design compromises needed to make it a seaplane. One prototype crashed in San Diego Bay in 1957, dooming the program. Although a clever concept, it still needed a mothership for refueling and rearming, and such servicing was made all the more difficult by the fact that the aircraft was not built to operate from a flight deck.

Yet another aircraft launch method was the aviation support ship. In World War II, the Imperial Japanese Navy took the unfinished battleship hull Shinano, the planned third Yamato-class battleship, and converted it to an aviation support ship. Instead of a true aircraft carrier, the Shinano would ferry spare aircraft to carriers at sea as well as refuel and rearm aircraft stationed on other carriers. In 1982, during the Falklands War, the Royal Navy implemented a similar concept, hastily fitting out the civilian roll-on/roll-off transport Atlantic Conveyor with a small takeoff and landing pad for AV-8 Harrier jets. The Atlantic Conveyor carried 14 Royal Air Force and Royal Navy Harriers, delivering them to the carriers HMS Hermes and HMS Invincible close to the battle zone.

But the aviation support ship concept has not caught on. Not cost effective in peacetime, a ship that has aircraft carrier-like qualities but not a permanent home for aircraft is viable only in circumstances of wartime desperation. It is perhaps no accident that both the Shinano and Atlantic Conveyor were sunk by enemy fire.

Today, aspects of many of these concepts could return, thanks to UAVs. The necessary technology already exists for unmanned airships to team up with UAVs to provide modern-day equivalents of the Akron-class airships.

A high-flying airship, equipped with sensors and networking capabilities, could reach its destination faster than a seaborne aircraft carrier and remain on station for days or weeks at a time. (See “Airships? Yes, Really!” Proceedings online, May 2019.) The airship could carry a battery of several dozen unmanned aerial vehicles, each equipped with radar, electro-optical, and other sensors, to extend the sensor reach of the mothership and hence the surface fleet. Those same drones could pack a variety of weapons for use against ships, submarines, lower-performance aircraft such as helicopters, and targets on land.

Attack airships would not replace traditional surface warships but instead augment them, providing a new layer of distributed lethality to the fleet and support for Marines and soldiers on the ground. Airships can screen large swathes of ocean where enemy contact is unlikely but some friendly sensor presence—backed up by weapons—would be useful. Convoys would gain access to improved situational awareness as well as an airborne antisubmarine warfare capability.

The past 100-plus years of naval aviation have seen experimental concepts come and go. Some, like the sea-launched fighter, are unlikely ever to come back. Others, such as the airship carrier, could return with a new twist. Cost issues notwithstanding, the aircraft carrier’s future seems fairly secure, but tomorrow’s fleet almost certainly will sail alongside other platforms that project air power in new and innovative ways.