On a warm Southern California day in June 1948, the USS Valley Forge (CV-45) returned to San Diego, completing an eight-month cruise around the world, the first by a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier. The carrier and escorting destroyers, the USS Lloyd Thomas (DD-764) and USS William C. Lawe (DD-763), entered port in the midst of growing great power competition between the United States and the Soviet Union. The Valley Forge’s early Cold War deployment provides a historical example of former Secretary of Defense James Mattis’ recent call for greater operational unpredictability in U.S. military deployments through the 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS).

The Valley Forge’s schedule changed three times as the Navy gradually extended her deployment, creating considerable uncertainty for anyone trying to predict her movements. The task force, commanded by Rear Admiral Harold Martin, originally left San Diego in October 1947 for three months of training based out of Hawaii followed by a planned six-month deployment to the Western Pacific with port visits in Australia, China, and Japan.1

In late February 1948, the task force received orders to circle the globe via the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean in response to turmoil in Palestine and U.S. fears about an upcoming Italian election. In April, concerns about Soviet intentions in Scandinavia resulted in added visits to Norway and the United Kingdom before the force returned to the West Coast via New York and the Panama Canal. In the course of roughly six months, the Valley Forge showed the flag in most of the regional crises facing the administration of President Harry Truman.

In one of his last acts as Commander in Chief, Pacific Command (CINCPAC) Admiral Louis Denfeld met in December 1947 with Australian Foreign Minister Dr. Herbert Evatt. The Australians wanted to secure a U.S. commitment to the defense of the South Pacific. When Denfeld raised the prospect of joint U.S. Navy-Royal Australian Navy (RAN) exercises, Evatt leaped at the opportunity.2 Accordingly, Denfeld ordered the Valley Forge, four destroyers, and an oiler to sail to Australia to train with the RAN followed by a stop in China before returning to Pearl Harbor.3 The Americans even invited six Australian naval officers to fly to Hawaii and observe carrier operations on the Valley Forge.4

The emphasis on assuring allies continued after the Valley Forge left Australian waters in early February. The task force stopped in Hong Kong and exercised with elements of the U.S. Seventh Fleet before arriving at Tsingtao, China, on 26 February 1948. The Americans resupplied from the local naval base, but the visit also provided a valuable show of support for the Nationalist Chinese in their struggle against the Chinese Communists under Mao Zedong. The Valley Forge’s visit and veritable mountains of U.S. aid, however, proved unable to prevent the defeat of the Nationalist Chinese by October 1949.

U.S. anxiety over increasing communist strength in China notably grew following the Soviet-backed coup d’état in Czechoslovakia in February 1948. Furthermore, the Truman administration worried about a communist victory, at the ballot box or in the streets, in the upcoming Italian elections scheduled for mid-April.

These concerns led the Navy on 26 February to order the Valley Forge to return to San Diego by sailing west, via the Suez and Panama Canals, instead of east.5 The unscheduled change in orders accomplished at least three purposes. First, the task force would reinforce the U.S. naval presence in the Mediterranean, then comprised of two other carriers and their escorts. This augmented force could influence Italian public opinion or respond if tensions between Arabs and Jews over the future of Palestine threatened U.S. lives or interests. Second, the new route would allow for a short detour into the Persian Gulf to visit Saudi Arabia. Finally, a snap circumnavigation would highlight U.S. military power projection which the Soviets could not match. The Valley Forge’s unpredictable course change assured allies in several regions of interest to the Truman administration.

After receiving these new orders, Task Force 38 headed south, passing through the Strait of Malacca and arriving in Saudi Arabia on 24 March. U.S. officials sought to bolster relations with the Saudi monarchy in light of U.S. support for the U.N.’s Palestinian partition. Despite efforts to reassure the Saudis, however, Truman’s decision in May 1948 to recognize the newly created state of Israel shocked the Saudi leaders. The Valley Forge and the two escorting destroyers left Saudi Arabia on 26 March and on 4 April she became heretofore the longest ship to transit the Suez Canal.6

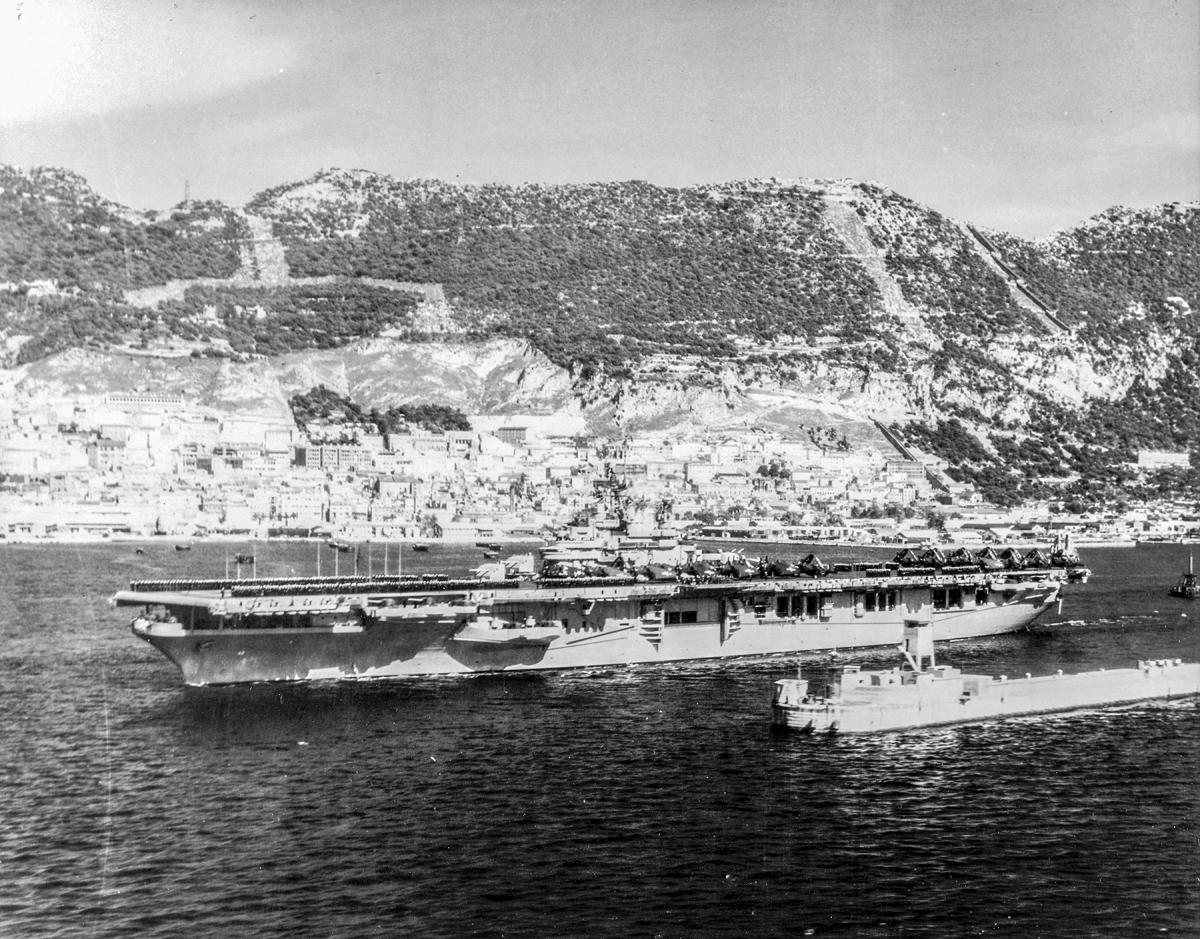

The next day the Navy Department announced another change in the task force’s schedule: the three ships would visit Norway for three days, from 29 April to 2 May, along with a squadron commanded by the senior U.S. Navy officer in Europe, Admiral Richard Conolly.7 Within a span of weeks, the Valley Forge would sail in both the warm Persian Gulf and the cold Norwegian Sea, underlining the inherent flexibility of seapower. Before heading north, however, the task force stood by at Gibraltar to watch the results of the 18 April Italian election.8

After a resounding electoral victory by the U.S.-backed Italian Christian Democrats, the Valley Forge sailed from Gibraltar and arrived at Bergen, Norway, in late April. In the wake of the Czech coup in February, the start of the Berlin Airlift on 1 April, and the signing of a treaty between Finland and the Soviet Union on 6 April, Norwegian leaders sought U.S. support. The Navy’s snap decision to send a squadron to Norway highlighted America’s rapid response capabilities which Norwegian officials “greatly appreciated.”9

After a short visit to the United Kingdom, the Valley Forge and escorts headed for New York. On 11 June, the Valley Forge arrived in San Diego, 246 days and 44,783 miles later, becoming the first U.S. carrier to circumnavigate the world. The trip demonstrated that the U.S. Navy could transform a short training trip into a global voyage with little warning or notice. Furthermore, the task force’s operations highlighted U.S. support for six allies and partners: Australia, Nationalist China, Saudi Arabia, Italy, Norway, and the United Kingdom.

Today the United States again faces rising competition from other great powers. Demands for the U.S. Navy to operate more unpredictably while still providing strategic assurance are less a new approach than a return to an older operating pattern. The carrier Valley Forge’s 1947–48 world cruise illustrates this early Cold War deployment model which sought to strengthen ties with U.S. allies while operating unpredictably, at least from the adversary’s perspective.

1. Barrett Tillman, VF-11/111 'Sundowners' 1942–95 (Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2010), 58; “Task Force to Visit Australia and China,” The New York Times, 7 December 1947; The Reminiscences of Rear Admiral Draper L. Kauffman, USN (Retired), Volume I, interview by John T. Mason, Jr., 5 December 1978, 319, Navy Department Library.

2. The Valley Forge cruise proved to be the second U.S. Navy task force to sail to Australia within a year as the carriers Antietam and Shangri-La visited in May 1947. Denfeld himself visited Australia in the summer of 1947. See Vice Admiral John Collins, RAN, Chief of the Naval Staff to Sir Frederick G. Shedden, Secretary, Department of Defense, June 12, 1947, 12/2, Discussions Chief of the Naval Staff ADM Denfeld USN; Record Group 11, Sea Power Centre - Australia, Canberra. The U.S. Navy has played a central role in maintaining American relations with Australia as detailed in Russell Parkin and David Lee, Great White Fleet to Coral Sea: Naval Strategy and the Development of Australia-United States Relations, 1900-1945 (Canberra, Australia: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2008).

3. “Task Force to Visit Australia and China,” 31; Rear Admiral Harold Farncomb, RAN, Flag Officer Commanding, HM Australian Squadron to Secretary, Naval Board (Australia), “A.F. 237/537/12, Exercises with Task Force 38,” February 23, 1948, 2002/2/215, National Archives of Australia.

4. “U.S. Gesture to R.A.N.,” Sydney Morning Herald, January 10, 1948, 2284/3, A5954, National Archives of Australia; Captain Wilfred Harrington, RAN to Secretary, Australian Commonwealth Naval Board, “Report on Visit to Pearl Harbour,” 17 February 1948, 1968/2/722, MP1049/5, National Archives of Australia.

5. “U.S. Carrier to Go to Arabia Trouble Spots,” Los Angeles Times, 27 February 1948; “Three More U.S. Warships Ordered to Near East,” Daily Boston Globe, 27 February 1948, .

6. “U.S.S. Valley Forge World Cruise, 1947-48,” 95.

7. Charles Hurd, “U.S. Naval Force to Visit Norway,” The New York Times, 6 April 1948.

8. “Valley Forge Here on World Journey,” The New York Times, 23 May 1948.

9. Rolf Tamnes, The United States and the Cold War in the High North (Dartmouth, NH: Dartmouth Pulbishing Co., 1991), 42; “‘Peace Ships’ in Bergen: U.S. Warships on Mission to Prevent Conflict, Envoy Says,” The New York Times, 3 May 1948.