Physical fitness carries many benefits, but great care must be taken to define it. As currently implemented, physical fitness programs in the U.S. armed forces have significant faults that negatively affect readiness and human health, including:

- Within each military service, the same physical fitness standards generally apply to all military occupations, though unneeded for many.

- Current programs ignore medical impediments to physical conditioning and fail to dissuade over-conditioning.

- Physical fitness testing algorithms create a perverse incentive to begin and continue tobacco use.

- The exclusive focus on conditioning heart and skeletal muscle overlooks the easily deconditioned organ most critical to modern military success: the brain.

In essence, the physical fitness programs of today’s armed forces are designed for the battles Homer’s Achilles fought at the gates of Troy, not for the battles the United States will fight at the gates of air, sea, space, and cyberspace. Although all services will fight these battles, Navy examples are cited here.

Policy

Department of Defense (DoD) physical fitness policies rest on two short statements. DoD Directive 1308.01 says service members “must possess the cardio-respiratory endurance, muscular strength and muscular endurance, together with desirable levels of body composition to successfully perform in accordance with their Service-specific mission and military specialty.” DoD Instruction 1308.02 defines a “fit” service member as one able to “meet the physical demands of their jobs for an extended period of time and to have the additional ability of meeting physical emergencies, such as those imposed during combat or other stressful situations.”

Physical fitness is not the entire story, however:

Overall Fitness = Medical Fitness + Physical Fitness

Medical fitness means all body organs function normally or a tolerable degree below normal. For example, Navy medical fitness standards establish 20/40 vision as tolerable in non-pilots, but not 20/800. Healed pneumonia is tolerable, but lung cancer never is.

Physical fitness means two organs—heart and skeletal muscle—function at some defined level above the normal disease-free level, enabling strenuous exertions. Physical conditioning makes this above-normal functioning possible.1

So, a SEAL developing 20/800 vision will be judged “unfit” for all military duties, despite retaining his superb physical fitness, because he is medically unfit.

Fault 1: Overly Stringent Requirements

Service members spend vast amounts of time exercising. Is that militarily worthwhile? For so-called battlefield service members, the answer obviously is yes. Anyone who must haul a pack or run after an enemy owes their effectiveness, and perhaps survival, to physical fitness.

But what of the rest of the force, who are not at the physical tip of the spear? Space and cyberspace operators fight while sitting down, far from bullets and bombs. Pilots increasingly are joining them, vacating cockpits for electronics-filled trailers, a trend that likely will continue. As Marshall of the Royal Air Force Sir Arthur “Bomber” Harris declared during World War II, “Our lead is in science, not spawn; in brains, not brawn.”1

For many service members, time spent cultivating muscles is difficult to justify. Time is valuable. Administrative duties balloon, duty training grows, and a historically small force (Navy end strength is 54 percent of that at the end of the Cold War) finds it still has just 24 hours in a day in which to squeeze all that is asked of it.

Moreover, innumerable non-fitness physical shortcomings are tolerated. Deployed troops carry with them eyeglasses, orthotics, inhalers, and pills . . . and pills . . . and pills. One deployment waiver was granted by the National Guard to an E-7 taking nine different medications. Given the large number of troops with sleep apnea in deployed locations, a history of our era could fairly be titled “CPAP Goes to War.” Why, then, are muscles so special, compared to eyes, feet, and sleep?

Physical fitness advocates would observe correctly that the unexpected is inevitable in wartime; unforeseen calamity can transform any member of the armed services into a battlefield service member. At sea, for example, damage control emergencies can demand strength and stamina at a moment’s notice. Still, are the odds of such calamities high enough to require the entire force to spend time practicing push-ups and sit-ups as Achilles did 3,000 years ago?

Continuing with this example, the Navy has made several decisions that seem to indicate it regards the odds of calamity as sea as so low that damage control compromises are tolerable. First, it is crewing Zumwalt-class ships with a complement of just 147, raising concerns about damage control effectiveness. Second, on board all ships, physical fitness requirements vary by age and sex, rather than being an absolute standard that derives, say, from the muscular effort required to shore up a holed hull. Third, the Navy permits sailors who carry HIV and other blood-borne viruses to serve at sea in large ships, apparently confident that the risk of briskly bleeding combat wounds is low enough not to endanger other sailors.2 Fourth, 7,700 at-sea positions in the Navy’s 280 ships will be unfilled in 2019.3 Yet, the Navy stands ready to freeze the career of a sailor who can do only 41 push-ups—as opposed to 42—in two minutes.

Consider next highly specialized personnel in short supply. Does it better serve a grievously wounded Marine that his surgeon spent years devoting four hours a week to strength training rather than reading medical journals or honing skills in the operating room? Is it better for a cyber operator or an airborne linguist to spend four hours a week on physical conditioning, or to take advanced courses for their profession? Should a submarine reactor officer train for a speedy 1.5-mile run when his duty world is not even 200 yards long? While some of these professionals may take pride in being overtly physically fit, others may see their time-consuming personal physical fitness requirements as a burdensome bureaucracy at work and leave the service, creating a difficult-to-fill vacancy.

If time and resources were infinite, all people could do all things. But they are not, so choices must be made. Once the odds of combat sword fighting neared zero, the Navy abandoned sword training, keeping those weapons only as ornaments for uniforms. More recently, leaders have recognized the probabilistic trade-offs between muscle and intellect in a resource-constrained environment. Admiral James Stavridis suggested “comparatively low physical-fitness standards” are appropriate for a force of military cyber professionals.4 And Admiral James Winnefeld advised young officers “to spend an extra hour a day, when all of the others around you are going to the gym, goofing off, or hanging around in the ready room [to teach] yourself something about your profession, whether it’s actually about your airplane or your ship or your submarine, or whether it’s reading a book.”5

For generations, medical standards in the armed forces have been tailored to military occupations, hence the existence of flying physicals, diving physicals, food-handler physicals, and dozens more. Physical fitness standards should be tailored to a manageable number of occupational categories, with the requirements in each derived from contingencies of reasonable probability.

Fault 2: Medical Optimization

Biological complexity offers several traps for the unwary, especially commanders (and occasionally physicians) who view physical fitness as a perfect state that naturally results from two virtuous activities: exercise and healthy eating. This naive belief leads to several false ideas.

The first is that failing a fitness test equates to personal failures in eating and training. While this may often be the case, the taxpayers may wish us to be sure before discarding their substantial training investment in an “unfit” military member.

As examples, anemia afflicts 25 percent of women in basic training and directly subverts aerobic fitness by reducing the transport of oxygen from the lungs to exercising muscles.6 Vitamin D deficiency, which significantly weakens muscles in all ages and even in athletes, is more common, especially in northern latitudes at the end of winter.7 Yet, neither condition is specifically checked during annual military medical examinations, neither is targeted by preventive education campaigns, and neither is checked by protocol in service members failing physical fitness tests.

If physical fitness is vital to the armed services, DoD should develop protocols to ensure these and other non-obvious medical conditions are not sabotaging service members’ success.

The second false idea is that more fitness is always better. Far from it. Of course, over-training increases injuries, but there is a more subtle and more deadly threat, stemming from Sir Charles Darwin’s principle that fitness is defined by the interplay between a living organism and its environment.

The Air Force paid with lives to rediscover this truth in the 1980s, after a mysterious series of fatal F-15 and F-16 crashes involving pilots who were enthusiastic distance runners. Their cardiovascular systems, as a result of superb conditioning in earth’s 1-G environment, had lost the reflexes to cope with the rapid-onset, high-G environment of the cockpit. The resulting surfeit of G-induced loss of consciousness cases was stemmed, in part, by restricting the weekly distances fighter pilots could run.

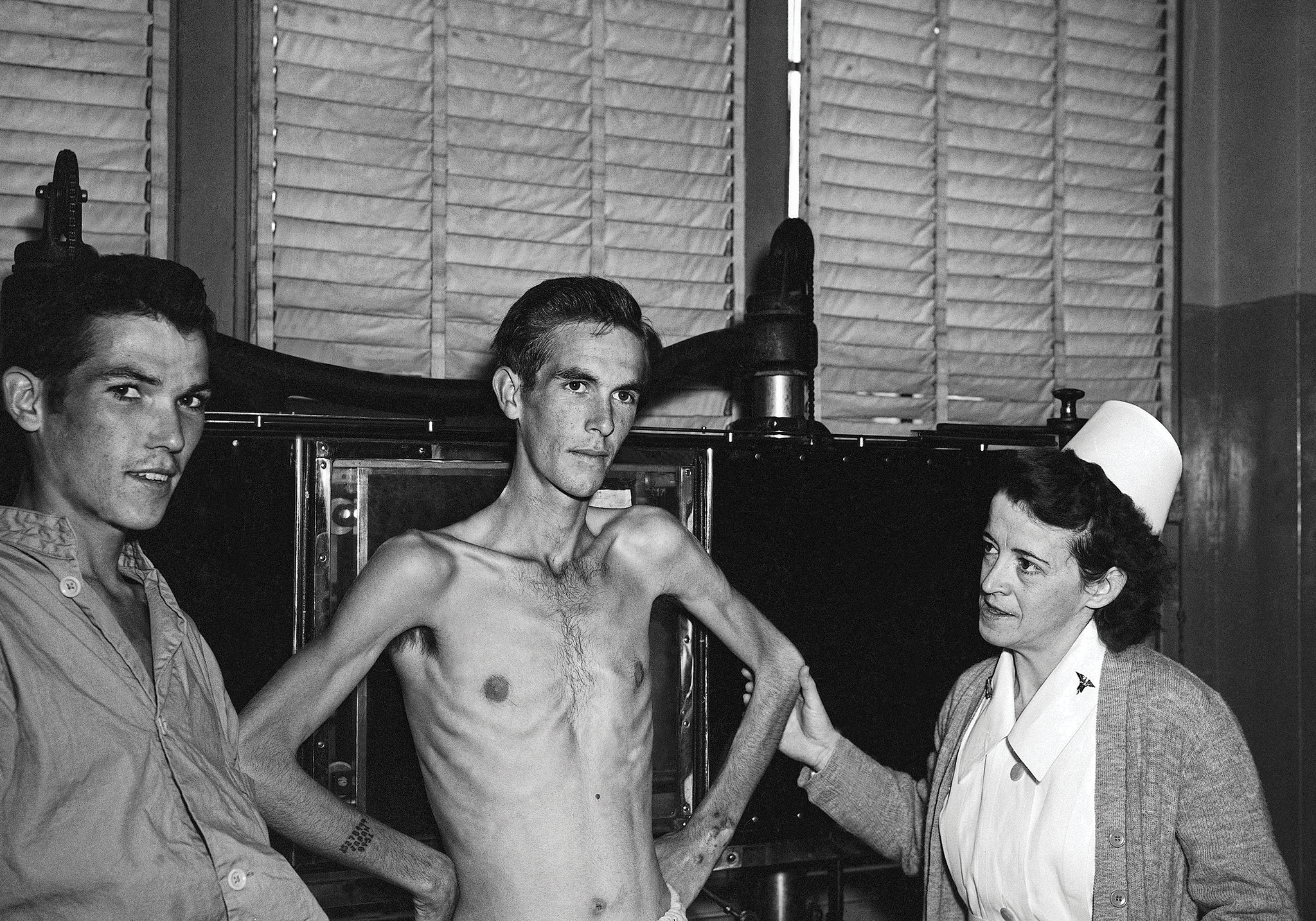

In a more mainstream example, DoD defines “desirable” body composition only by a maximum allowed fatness. Body fat minimums are neither advised nor required, so fat is vilified by some physical fitness enthusiasts, who labor at every turn to minimize theirs. Of concern, this aggressive fat-minimization requires food in abundance, thereby making a person metabolically unfit for an environment of food scarcity . . . which is precisely the environment U.S. prisoners of war have endured over the past 150 years. So, too, for months during 1941-42, General Douglas MacArthur’s disintegrating army of 100,000 in the Philippines faced half rations, then third rations, then quarter rations.8

Ironically, the most-conditioned service members face the gravest danger from calorie scarcity. An athlete whose caloric intake drops from his or her usual 4,000 calories per day to 500 develops clinical calorie deficiency sooner than a non-athlete whose usual intake is 2,000 calories per day. This was obvious to Union soldier John McElroy, who spent 16 months starving in Confederacy prison camps during the Civil War, where he discerned “a general law, the workings of which few in the army failed to notice. It was always the large and strong who first succumbed to hardship. The stalwart, huge-limbed, toil-inured man sank down earliest on the march, yielded soonest to malarial influences, and fell first. . . . I can recall few or no instances where a large, strong, ‘hearty’ man lived through a few months of imprisonment.”9

British nutritionists in World War I knew “a certain degree of surplus consumption is absolutely essential. The soldier in training for the battlefield should carry on his own person reserves in the form of fat or other material. The only method by which these internal reserves can be formed is by giving a definite surplus of food for long periods before the strain begins.”10 During World War II, “a boy or young man robust enough to serve in the United States Navy carried, on average, about 20 percent body fat and could live under ordinary circumstances for perhaps three weeks without food.”11

Ounce for ounce, fat stores more than twice the calories muscle does and preserves muscle supply. Physiologically, it is the POW’s or hostage’s best friend. The military’s unbridled hostility to body fat, part of its “culture of fitness,” should be moderated to include guidance on body-fat minimums.

Fault 3: Tobacco

Because cigarette smoking causes weight loss, and because quitting smoking causes weight gain (85 percent of quitters gain weight12), and because fatness is penalized in physical fitness testing but tobacco use is not, a perverse and unconscionable incentive to begin and continue using tobacco has been institutionalized in the U.S. armed forces.13

While Navy policy expressly forbids certain maneuvers for temporarily changing body shape, such as sauna suits and body wraps, it makes no proscriptions against smoking. One may argue that no sensible person would use tobacco to pass body fat testing, but desperation often trumps common sense, and such cases have occurred.

Current fitness testing algorithms should be reformulated immediately to penalize tobacco use. The simplest approach would be to subtract points when nicotine metabolites are detected in routine urine drug screens, a change having minuscule cost and zero inconvenience.

To make tobacco cessation—and the associated weight gain—unthreatening, anyone whose medical record documents tobacco use over the preceding two years should be eligible for a two-year exemption from body composition testing, assuming that regular substance monitoring shows continuous abstinence from tobacco. Exemption is medically advisable because, statistically, tobacco quitters who gain weight live longer than quitters who don’t gain.14

Tobacco’s costs and negative effects on readiness are numerous, well-documented, and substantial.15 Eliminating it would benefit service members and the military’s capabilities faster and more significantly than would force-wide perfection on physical fitness scores.

Fault 4: Overlooking the Brain

Achilles fell without defeating Troy, but clever Odysseus succeeded by inventing the Trojan Horse. Odysseus was a prototypical “cognitive warrior,” whose martial strength rose predominantly from his thoughts, not from straining muscles or battle equipment.

The effectiveness of the United States’ cognitive warriors relies on the function of a physical organ so sensitive that its operation noticeably degrades after just an extra hour of routine wakeful use: the brain. Ridiculous as it may seem, the physical activity that most enhances the lethality of a cognitive warrior is sleep, because brain fatigue is the factor that most diminishes it. Brisk hour-long daily walks should suffice for tuning the cardiovascular system that supplies the brain’s energy and for preventing the aches and pains that sedentary workplaces breed.

Cognitive warriors deserve special brain-focused medical examinations, especially to identify and treat widespread sleep-degrading diseases that normal military examinations miss. A 2013 study of recently deployed active-duty Army troops having sleep complaints showed that 50 percent had obstructive sleep apnea sufficiently severe to fog the brain and that 88 percent had some disease of sleep.16 Worse, for all of us who once disdained sleep, evidence is starting to implicate sleep disruption in causing Alzheimer disease.17

A physical fitness test for a brain would measure how long the brain could sustain attention before fatiguing. Such tests could be implemented using simple personal tech, a book, and a chair, with points deducted if caffeine is used.

Improved brain physical fitness is the best possible tool to prevent those military calamities that would demand muscular fitness. Every commander in the fleet would prefer alert, thinking sailors over dulled, muscle-bound sailors.

Achilles and Odysseus

Physical fitness can benefit military forces operationally and by generating pride. But unnecessary physical fitness is at a minimum wasteful, and potentially harmful to the mission. In his prize-winning essay, “Cyber War Requires Cyber Marines,” Marine Major Nick Brunetti-Lihach perceptively observed that “the definition of martial strength must be expanded” beyond traditional notions.18 A modern military force must have its Achilles and its Odysseus—and neither must be under- or over-conditioned.

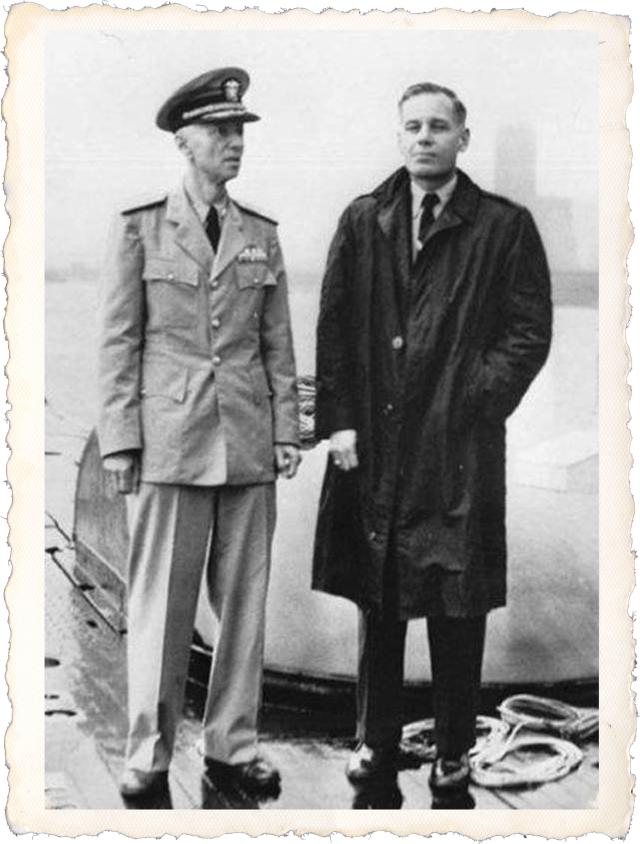

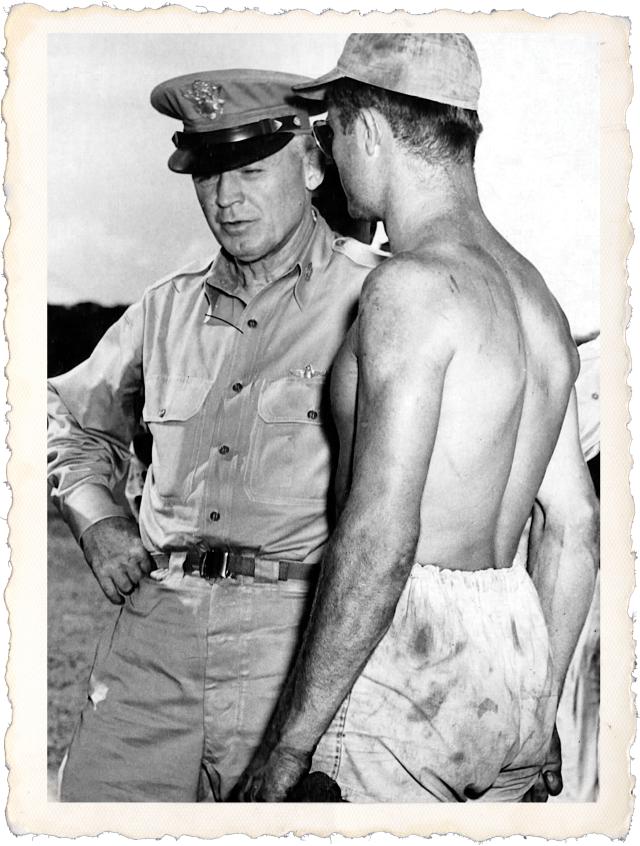

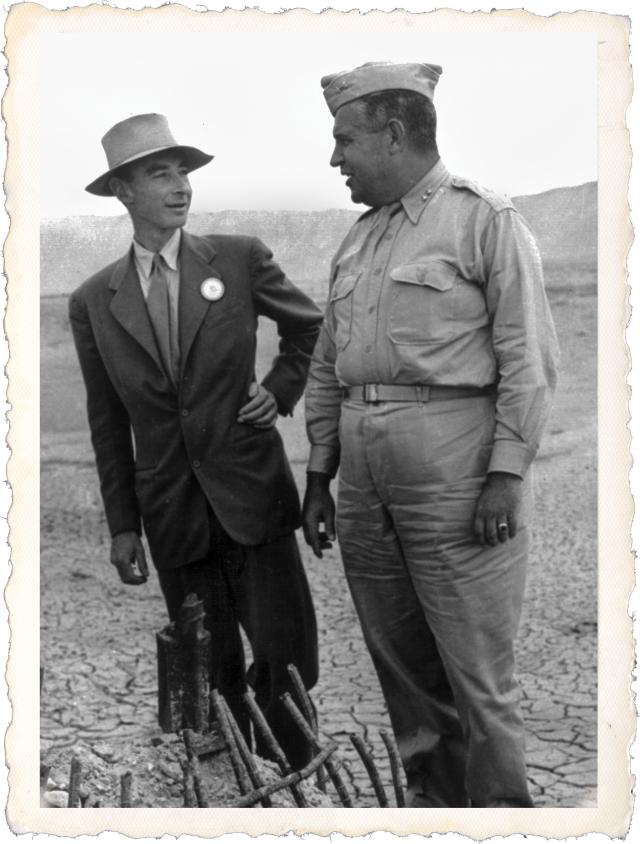

Elite 20th-Century Cognitive Warriors in Uniform

1. Thomas M. Coffey, Decision Over Schweinfurt: The U.S. 8th Air Force Battle for Daylight Bombing (New York: David McKay, 1977), 134.

2. Matthew M. Burke, “Navy Opens More Assignments to HIV-positive Sailors, Marines,” Stars and Stripes, 1 November 2013.

3. Shawn Isbell, “Detailing and Placement,” Navy Personnel Command, November 2018.

4. ADM James Stavridis, USN (Ret.), and David Weinstein, “Time for a U.S. Cyber Force,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 140, no. 1 (January 2014).

5. ADM James A. Winnefeld Jr., USN, “You Have to Be a Good Thinker,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 141, no. 8 (August 2015): 16−21.

6. Kathryn E. Myhre, et al., “Prevalence and Impact of Anemia on Basic Trainees in the U.S. Air Force,” Sports Medicine–Open 2, no. 23 (December 2016).

7. G. L. Close, et al., “Assessment of Vitamin D Concentration in Non-supplemented Professional Athletes and Healthy Adults during the Winter Months in the UK: Implications for Skeletal Muscle Function,” Journal of Sports Sciences 31 (2013): 344–53. Kate A. Ward, et al., “Vitamin D Status and Muscle Function in Post-menarchal Adolescent Girls,” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 94 (2009): 559–63. Michael F. Holick, “High Prevalence of Vitamin D Inadequacy and Implications for Health,” Mayo Clinic Proceedings 81 (2006): 353−73.

8. John Bumgarner, Parade of the Dead (Jefferson, NC: Mcfarland, 1995), 68−69.

9. John McElroy, Andersonville: A Story of Rebel Military Prisons (Greenwich, CT: Fawcett, 1962), 45−46.

10. John Ellis, Eye-Deep in Hell: Trench Warfare in World War I (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989), 125.

11. Bob Drury and Tom Clavin, Halsey’s Typhoon (New York: Grove Press, 2007), 239.

12. Henri-Jean Aubin, et al., “Weight Gain in Smokers after Quitting Cigarettes: Meta-analysis,” British Medical Journal 345 (2012): e4439.

13. Dennis S. O’Leary, “Decision Brief: Obesity/Overweight in the Military,” Defense Health Board, 18 November 2013.

14. Yang Hu, et al., “Smoking Cessation, Weight Change, Type 2 Diabetes, and Mortality,” New England Journal of Medicine 379 (2018): 623−32.

15. Institute of Medicine, Combating Tobacco Use in Military and Veteran Populations (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009).

16. Vincent Mysliwiec, et al., “Sleep Disorders in U.S. Military Personnel: A High Rate of Comorbid Insomnia and Obstructive Sleep Apnea,” Chest 144 (2013): 549–57.

17. Ehsan Shokri-Kojori, et al., “Beta-amyloid Accumulation in the Human Brain after One Night of Sleep Deprivation,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 115 (2018): 4483−88.

18. MAJ Nick Brunetti-Lihach, USMC, “Cyber War Requires Cyber Marines,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 144, no. 11 (November 2018): 18−23.