As hurricanes increase in intensity, the demand for Coast Guard abilities is growing. With resources stretched thin, handling response operations in addition to safety and protection missions is difficult. (U.S. Coast Guard/Lisa Ferdinando)

When Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico on 24 September 2017, it devastated the island’s power grid, leaving citizens without electricity for months. Resources became scarce, and prices for basic commodities skyrocketed. But Maria was just one of three major hurricanes to make landfall in the United States in the summer of 2017; Hurricane Harvey plowed through Texas, and Irma deluged the Caribbean and southeastern states. While the causality of climate change is widely debated, the 2017 hurricane season serves as growing evidence of the earth’s shifting climate.

“Climate change” is the term used to describe the effects of global air temperature rise. One of the effects is stronger and more intense hurricanes, but there is another concern: sea level rise caused by the combination of thawing glaciers, thermal expansion of the water itself, and ice sheet loss from Greenland and West Antarctica.1

Higher sea levels not only worsen the effects of hurricanes but also intensify large rain events and coastal flooding, with the potential to cripple cities both physically and economically. Strong storm surges can break sea walls and disable ports, and rising waters can drown power delivery systems and leave roads, bridges, and runways awash, disrupting land, sea, and air transportation and the supply chain.

Unfortunately, military installations are not immune to these effects.2 Climate trends threaten infrastructure, assets, force readiness, and, therefore, national security.

The Coast Guard’s Role

The U.S. Coast Guard plays a key role in national security, responsible for protecting the U.S. maritime domain and transportation system—ports, waterways, and coasts. During the 1 June to 30 November hurricane season, this becomes particularly demanding for the smallest of the five military branches.

When Maria hit Puerto Rico, Coast Guard resources already were stretched thin responding to hurricanes Harvey and Irma. Active-duty personnel were pulled from their primary duties, and reserve forces were activated, some tasked to stand watch at the National Response Coordination Center, while others deployed in direct support of response operations. During relief efforts in Puerto Rico, a Coast Guard liaison officer reported multiple failed efforts to acquire a Coast Guard helicopter for aerial observations because the aircraft was delivering food and water to affected residents. This resulted in a delay in the concurrent post-storm mission to monitor the safety of navigable waterways and degraded readiness in the face of dual missions.

“Doing more with less” has become a Coast Guard mantra over the years. The U.S. Coast Guard fact sheet from the 2019 President’s budget, for example, includes the service life extension for the MH-60T Jayhawk helicopter.3 While “life extension” sounds nice, in reality, it equates to a lack of funding for new procurement. The service life extension program aims to add 10,000 flight hours to the Jayhawks to keep them operational through the mid-2030s. Many of these helicopters have been in service since 1990.4

Why can’t the Coast Guard be doing more with more? As waters rise, storms surge, and hurricanes squall, the demand for Coast Guard abilities is growing. This is a challenge for both personnel and assets.

Hitting Home Base(s)

Protecting Coast Guard capabilities is just as important as increasing them. Coastal landscapes are shifting, and failure to adapt accordingly compromises force readiness. With small-boat and air stations, training centers, and bases situated on or near water, Coast Guard infrastructure is especially susceptible to flooding events.

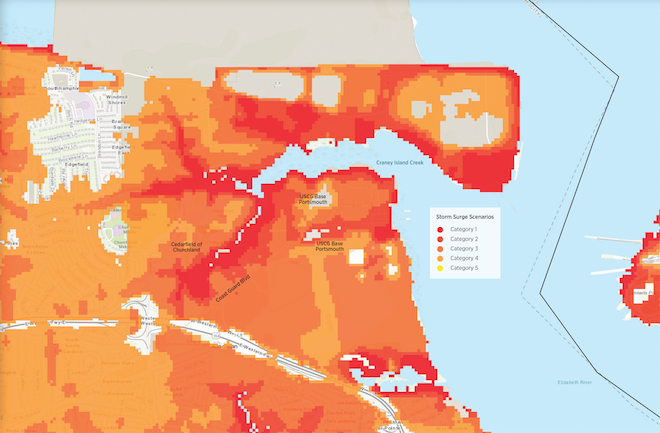

Based on a coastal flooding exposure mapper from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, several major Coast Guard installations—including Training Center Cape May, Base Portsmouth, and Air Station Clearwater—would be heavily affected by storm surge.5

Air Station Clearwater is the largest and busiest air station in the Coast Guard, serving the shorelines of Florida, the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean Basin, and the Bahamas. The entire footprint of the station would be affected by category one storm surge. Training Center Cape May is where new recruits are trained and is responsible for supplying the entire Coast Guard enlisted workforce. In storm surge category three, would training still be possible? Base Portsmouth supports the Coast Guard Atlantic Area, which has responsibility from east of the Rocky Mountains to the Arabian Gulf. Portsmouth fares slightly better with a leveed pocket of resilience at the maximum category five storm surge. (See map below.)

What now?

The Coast Guard has a responsibility to prepare for operations as climate conditions become more unpredictable. Serious strategic investment is crucial in ensuring resiliency, managing risk, and maintaining operational readiness. A February 2018 Military Expert Panel Report addresses sea-level rise and the risks it poses to coastal military installations and makes the following recommendations:

• Continually identify and build capacity to address infrastructural, operational and strategic risks.

• Integrate climate impact scenarios and projections into regular planning cycles.

• Make climate-related decisions that incorporate the entire range of risk projections.

• Model catastrophic scenarios and incorporate into planning and war-gaming exercises.

• Work with international counterparts at key coastal bases abroad.

• Track trends in climate impact as uncertainty levels are reduced.

• Maintain close collaboration with adjacent civilian communities.

• Continue to invest in improvements in climate data and analysis.6

Coast Guard-specific strategies should include site vulnerability assessments that incorporate climate trends; integration of projected sea level changes in short- and long-term planning cycles, with contingency plans and exercises updated accordingly; replacement of aging aerial and maritime platforms in anticipation of increasing demands; increasing local and maritime partnerships to discuss climate strategies going forward; and potential relocation of assets and permanent migration of installations to less-vulnerable locations.

The Coast Guard should be at the forefront of climate change—ahead of the wave, not teetering on the crest. Regardless of debated causality, the consequences of climate shift already are appearing. Last year’s Atlantic hurricane season caused $202.6 billion in damages, officially the most expensive hurricane season ever.7 Stronger investment in the Coast Guard is crucial to remaining Semper Paratus.

1. NASA, “How Climate Is Changing,” and “Sea Level Rise,” National Geographic, 13 January 2017.

2. “Sea Level Rise and the Military’s Mission,” 2nd ed., Military Expert Panel Report (February 2018).

3. “U.S. Coast Guard Fact Sheet,” Fiscal Year 2019 President’s Budget, 12 February 2018.

4. Coast Guard Acquisition Directorate, “MH-60T Service Life Extension Project."

5. NOAA, Coastal Flood Exposure Mapper.

6. “Sea Level Rise and the Military’s Mission.”

7. Brian K. Sullivan, “The Most Expensive U.S. Hurricane Season Ever: By the Numbers,” Bloomberg.com, 26 November 2017.

Lieutenant Kwok is stationed at Coast Guard Headquarters, Washington, DC, Office of Port and Facility Compliance. She is a marine safety officer previously stationed in Sectors St. Petersburg, Juneau, and North Carolina. She currently is attending the Virginia Tech Center for Leadership in Global Sustainability in pursuit of a master’s degree in natural resources.