The USS Somerset (LPD-25) transits the Pacific in 2016. The LPD-17 design requires unique shiphandling considerations.

Well over a decade since the first San Antonio (LPD-17)–class amphibious transport dock was delivered to the Navy, it has become a cornerstone in the future design and construction of amphibious warships. Intended as the functional replacement for the aging amphibious ships in the Austin (LPD-4) class, Anchorage (LSD-36) class, Charleston (LKA-113) class, and Newport (LST-1179) class, the fiscal year 2018 budget allocated funds toward a Flight II variant of LPD-17 to replace the Whidbey Island (LSD-41) class. By 2030, the San Antonio design will form the majority of the amphibious fleet and ultimately will consist of 26 ships—13 Flight I and 13 Flight II—making it the central platform of modern amphibious warfare.

Based on the experiences of many San Antonio–class captains and shiphandlers, we capture here the nuances of the class, highlighting the unique LPD-17 characteristics that at times require a deviation from shiphandling “norms” taught to cruiser and destroyer counterparts.

The Ship

The key characteristics of the San Antonio are:

• At 684 feet long with a 105-foot-wide beam, the San Antonio is nearly 180 feet shorter than the USS Makin Island (LHD-8) but carries nearly the same beam width to accommodate large aircraft such as the MV-22 Osprey.

• At 25,000 tons for full load displacement, the LPD-17 is more than two and one-half times the displacement of an Arleigh Burke–class destroyer. When fully loaded with 38,182 square feet of vehicle storage, 319,000 gallons of aircraft fuel, and two landing craft air cushions (LCACs) or one landing craft utility (LCU) in its well deck, the LPD becomes significantly heavier and more difficult to maneuver.

• The ship’s normal navigational draft is just over 23 feet, 7 feet shallower than that of an Arleigh Burke. When ballasted for well-deck operations, the draft can increase to nearly 32 feet astern.

• LPD-17 is propelled by two shafts, each coupled to two Colt-Pielstick 2.5 STC diesel engines, delivering nearly 42,000 brake-horsepower. This yields a significantly reduced power-to-weight ratio of less than 2:1, compared with the powerboat-like 10:1 ratio for destroyers.

• Power is delivered by two independent controllable-pitch, five-bladed, 16-foot propellers capable of 165 revolutions per minute. To best accommodate amphibious operations, these propellers rotate inward (port shaft rotates clockwise, starboard shaft rotates counterclockwise).

• The rudders are much larger than those of smaller warships, providing a billboard-like 195-square-foot surface area and weighing nearly 50,000 pounds apiece. These large rudders create substantial drag and lift, giving LPD-17 a tighter turning radius during deceleration. This makes large rudder orders (35 degrees) more significant when needing to turn quickly with minimal advance and transfer, or when conducting a twist.

• The hull form includes a large round bottom, allowing the ship to move easily through the water, but leaves it susceptible to rolling in rougher seas. It does not experience the same heel as does an Arleigh Burke or a Ticonderoga-class cruiser when conducting a tight turn.

• The ship’s sail area above the waterline, due to enclosed masts and an elongated superstructure, extends from forecastle to flight deck. This makes the San Antonio far more susceptible to wind than the Arleigh Burke. Of note, beginning with LPD-29, every San Antonio–class LPD will feature a traditional “stick mast” as opposed to enclosed masts.

Maneuverability

The San Antonio is the largest U.S. warship without a flight deck bow-to-stern. As such, many standard shiphandling principles for medium-small combatants apply. Furthermore, with a centerline pilothouse and bridge wings that extend the entirety of the ship’s width, the ship enjoys an arc of visibility similar to that of a smaller warship. Thus, it is only the large size of the San Antonio that gives the ship some unique shiphandling characteristics.

The rounded bottom of the LPD hull makes the vessel well balanced, resulting in a normally smooth ride when transiting. When turning with a full bell and full rudder, the ship heels significantly less than a destroyer. The tradeoff comes in the form of drastic deceleration through the turn—a 180-degree turn starting at 18 knots with full rudder sees the ship typically decelerate to less than 10 knots by the time the helm reaches the reciprocal course. While this does not affect the vessel’s tactical diameter, it increases the time needed to bring the ship to a new course.

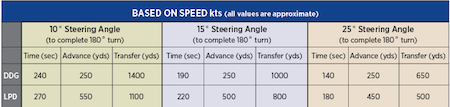

The San Antonio boasts a surprisingly tighter tactical diameter than the Arleigh Burke. This largely is a result of a pivot point that frequently can be manipulated far forward when engaged in a turn, delivering a narrower radius as the consequence of severe deceleration through the turn. The table above compares the advance and transfer of the two classes, which illustrates this significant difference.

When rudder is applied, a destroyer reacts almost immediately, arcing a turn that results in a lower advance value than a San Antonio–class LPD achieves. However, an Arleigh Burke is able to carry the majority of her speed through the turn, experiencing only an incremental 10–20 percent reduction in speed at the start of the turn, which results in a wider transfer value. By carrying more speed through the turn, the pivot point just aft of the pilothouse remains relatively fixed, allowing the destroyer to make the aggressive, swinging turn displayed in glossy wardroom farewell pictures.

By comparison, the San Antonio’s pivot point moves forward through the turn due to the loss of speed. While the turn takes longer to develop (and yields an advance distance that overshoots the destroyer’s), once the speed bleeds off, the pivot point slides forward and delivers an impressively satisfying rate of swing by the stern, completing the turn with less lateral distance traveled and a tighter turn when reversing course. This requires significant consideration during restricted-waters transits. With more than 500 feet of ship aft of the pivot point, caution is warranted when making a large turn, always ensuring the stern will safely swing clear of buoys and shoal water.

One of the key considerations when handling the San Antonio is recognizing the importance of momentum. Both course and speed changes require more foresight than required for the Arleigh Burke. Due to the lower horsepower-to-weight ratio and the rounded hull, the San Antonio is most likely limited to about 22 knots depending on the cleanliness of the hull, unlike the more than 30 knots of speed available to destroyers and cruisers. Additionally, LPD-17’s Colt-Pielstick diesel engines require significantly more time than a gas-turbine propulsion plant to start and clutch in, limiting the shiphandler’s ability to build speed on short notice. Thus, the shiphandler must prevent placing the ship in a position requiring a sudden increase in speed.

The Sail and Hull

The San Antonio’s shallow draft and large sail area make wind a much more impressive force than it is for a destroyer or cruiser. The traditional rule of thumb taught to surface warfare officers is that 30 knots of wind equals one knot of current. The LPD-17 shiphandler must be far more conservative—low-speed evolutions in greater than 15 knots of wind can cause the ship to experience a twisting effect due to the large sail area, making it difficult for the helmsman to maintain a steady course. This twisting, compounded with the already prevalent effects of set and drift, can create a challenging situation in high-risk, low-speed evolutions. For LPD-17 shiphandlers, a better rule of thumb is 20 knots of wind is equivalent to a knot of current.

The San Antonio’s shape and hull form, designed to minimize radar cross-section, contains various idiosyncrasies that impact the watchstander’s field of view. The shadow zone—the area near to the ship that cannot be seen by bridge watchstanders—is significant. Based on the bridge’s 75-foot height-of-eye, the shadow zone extends nearly 150 feet forward. This can create an unsettling “seaman’s eye” view when mooring near the head of a pier. Additionally, there is a distinct angular change in the shape of the hull between the freeboard (main-deck level) and waterline, commonly referred to as the “knuckle.” The knuckle resides about 20 feet above the waterline and creates a shadow zone along the port and starboard beams, resulting in a 5–7 foot shadow zone obscuring the bridge team’s view to monitor small-boat operations or man-overboard recoveries.

Man Overboard

San Antonio–class LPD man-overboard procedures are untraditional. While the LPD-17 has deployable rigid hull inflatable boats (RHIBs) on both sides of the ship, only the starboard side RHIB can be considered a ready lifeboat for emergencies. However, the San Antonio lacks traditional J-bar davits on either side of the ship. Any man overboard must be approached on the port side using the port side-port shell door, the only location from which a rescue swimmer can be lowered into the water.

When executing a shipboard recovery, surface warfare officers are taught “Anderson by day, Williamson by night.” This means that a shiphandler will perform an Anderson turn during the day if the person in the water is visible. At night, or when the location of the person is unknown, the ship does a Williamson turn and returns down a reciprocal course. The port-side recovery requirement and susceptibility to wind make this memory aid problematic for the San Antonio bridge team. During all recoveries, a commonly taught principle is “wind, ship, man,” meaning the ship should always be upwind and set down on the person in the water. This is even more important for the San Antonio. The ship’s large sail area coupled with a port-side recovery requirement makes wind the critical factor in positioning for the slow speed recovery. A Williamson turn in certain conditions, even during the day with the person’s position known, may be a better choice.

Underway Replenishment

For underway replenishment, the biggest factors for the San Antonio are momentum (the LPD reacts slowly to speed changes) and the Venturi effect. With the ship in waiting station 300–500 yards off the quarter of the oiler, a full bell of 18 knots will not achieve the ordered speed by the time speed needs to be reduced. Instead, the ship may only reach 15–16 knots by the time the bullnose passes the flight deck of the oiler and the San Antonio needs to slow to the optimum replenishment speed. Carry the momentum 30 seconds too long and the ship will sail past the oiler, placing the bow well forward of the oiler’s bow. Additionally, due to LPD-17’s size, the low-pressure system created alongside during approach to the oiler is more pronounced than when a destroyer or cruiser approaches. This interaction can cause the San Antonio and the oiler to experience a stronger “suction” effect, which can be hazardous if the approach starts off too narrow. Since LPD-17 lacks the acceleration to power out of a situation based on speed alone, it’s crucial that the approach be performed with a conservative lateral separation no closer than 200 feet. Once alongside, the ship can settle in and close lateral separation as needed to fire shot lines and replenish.

While there are some unique characteristics of the San Antonio–class LPD, she can be handled as deftly as a destroyer or cruiser. Traditional shiphandling principles still determine maneuvering effectiveness, and it falls to surface warfare officers and their bridge teams to understand this vessel’s capabilities and limitations. The LPD-17 hull form will be central to the future amphibious fleet, and in documenting these shiphandling lessons we hope to benefit future surface warfare officers and shiphandlers. After all, shiphandling is the craft that always places the surface warfare profession on display. Let’s be great at it.

Captain DeVore is a career surface warfare officer, having commanded the patrol coastal ships USS Typhoon (PC-5) and USS Hurricane (PC-3), the destroyer USS Stethem (DDG-63), and currently the amphibious transport dock USS New York (LPD-21).

Lieutenant Murphy is a surface warfare officer who has served on board the destroyer USS Mahan (DDG-72) and currently is navigator on board the USS New York (LPD-21).