As both a naval officer and a naval historian, I recommend the Navy secure the First Navy Jack and restore the traditional Navy jack.

In port, every U.S. Navy ship flies two flags. At the stern is the national ensign, and at the bow flies the Navy jack. Traditionally, the Navy jack has been the inset of the national ensign—stars for each state on a field of blue. For the past 17 years, however, all U.S. Navy ships have flown the “First Navy Jack,” a flag with 13 red and white stripes, a rattlesnake, and the words, “Don’t Tread on Me.”

Use of the First Navy Jack was directed by then-Secretary of the Navy Gordon England in May 2002. Secretary England wrote: “From the very beginning of our Navy, the Jack has been used on board American warships. . . . The temporary substitution of this Jack represents an historic reminder of the nation’s and Navy’s origin and will to persevere and triumph.” The Secretary ordered that the First Navy Jack remain flying until the end of the Global War on Terror.

Regrettably, the First Navy Jack probably is not the actual first jack of the U.S. Navy. The jack that the first commander-in-chief of the U.S. Navy, Esek Hopkins, ordered his ships to fly in January 1776 was described simply as a “strip’d jack.” His instructions made no mention of a rattlesnake or “Don’t Tread on Me.” Hopkins did fly a rattlesnake flag known as the Gadsden flag, but it had a plain yellow background and served as his personal standard. At the time, most American merchant ships frequently displayed a red-and-white striped flag, and in all probability, the first Navy jack was a similar striped flag.

None of this is recent news. The Naval History and Heritage Command website states that the design of the First Navy Jack “rests on no firm base of historical evidence.” The North American Vexillological Association, dedicated to the scientific study of flags, awarded their 2002 William Driver Award to Peter Ansoff, whose research concluded that “while the rattlesnake-and-stripes flag that currently flies on the bow of every U.S. warship has a long tradition in American flag use, its design was a 19th-century mistake based on an erroneous 1776 engraving.” In fact, the flag we call the First Navy Jack actually was not flown on board a U.S. Navy ship until 1975, when it was used as part of the bicentennial celebrations.

Moreover, whatever the first Navy jack really was, it was flown during an inauspicious time in our Navy’s history. Esek Hopkins and his little fleet pulled off a successful amphibious raid on Nassau, but they did so while ignoring congressional directives. Hopkins and his squadron captured two small Royal Navy warships, but they allowed a Royal Navy frigate to escape from their formation and then were blockaded in port. As a result of congressional dissatisfaction with his performance, Hopkins was censured and relieved of command.

At best, the First Navy Jack is historically unsupportable and represents the embarrassing initial missteps of the U.S. Navy. At worst, it is encumbered by a superstitious sailor’s worst enemy: bad luck, a superstition that a multitude of events and programs over the past 17 years seems to support.

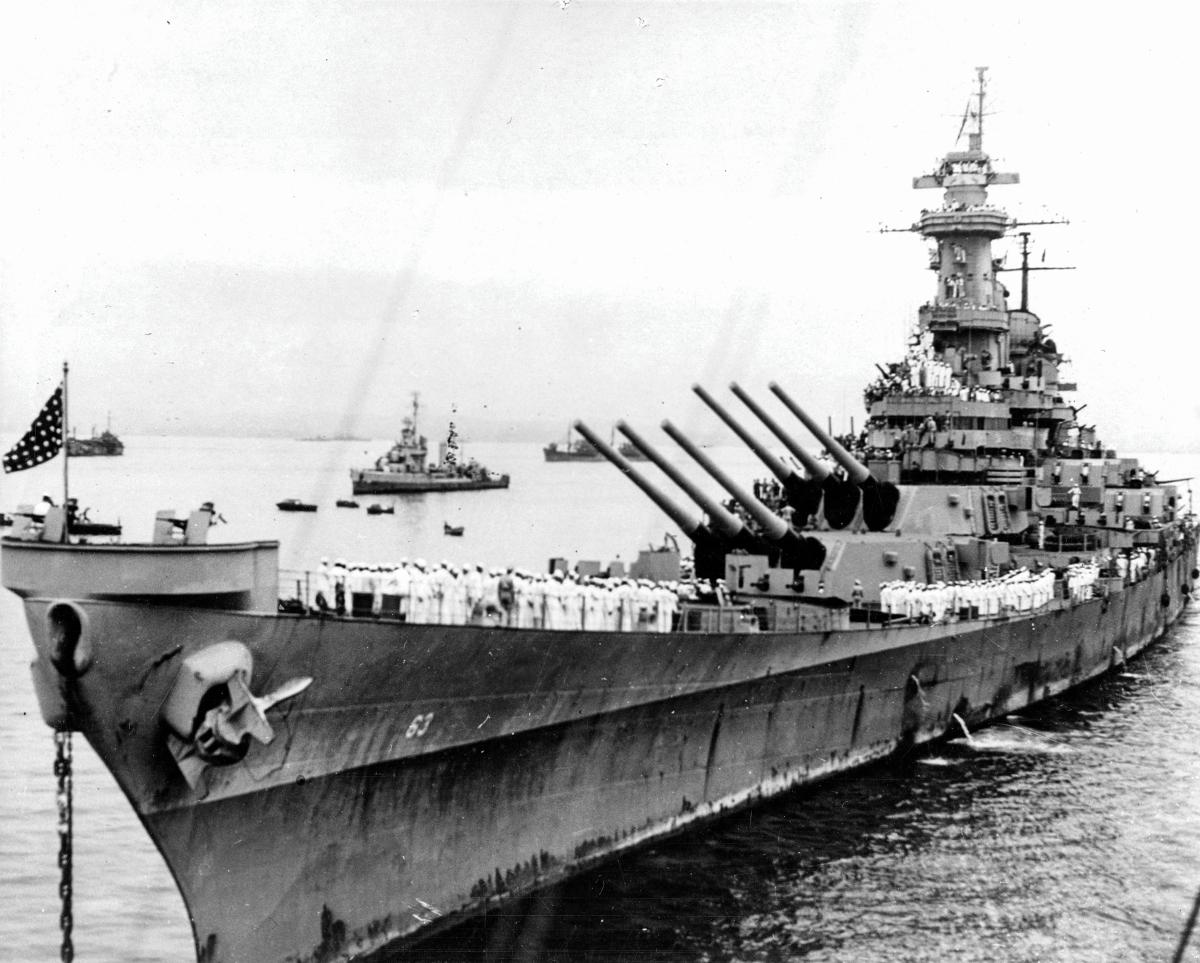

It is time to secure the First Navy Jack and use the traditional Navy jack, which has a long and storied history. The traditional Navy jack actually did fly during the American Revolution. It flew on board the USS Constitution during the War of 1812. And it flew on the bow of the USS Missouri during the Japanese surrender ceremony. And instead of the prickly warning that the First Navy Jack symbolizes, the traditional Navy jack is a reminder of the indivisible strength of our union. Just as Secretary England intended when he wrote that the use of the First Navy Jack would be “temporary,” the traditional jack can be raised to end one period of our Navy’s history and reconnect us to our distinguished past.

The past 17 years have been a time of great change in our Navy: new uniforms, new ships, and new policies. It’s time to change back to one of our best traditions, the U.S. Navy jack that flew proudly for more than 200 years, in times of peace and war.